It’s been two years since 43 Mexican students disappeared, and we still don’t know exactly what happened to them

The 43 students, young men who had been studying at a teachers college in the rural town of Ayotzinapa, had hijacked buses in hopes of reaching a demonstration.

Reporting from Mexico City — Two years after 43 Mexican college students vanished in the southwestern city of Iguala, the case remains a grisly mystery and a dark stain on the administration of Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto.

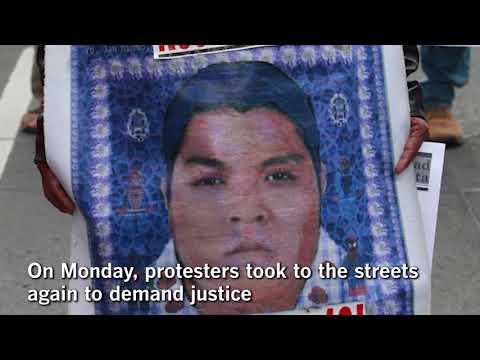

The public anger was on display Monday — the anniversary of the presumed mass killing — in Mexico City, where thousands of protesters took to the streets to demand justice. The 43 students, all young men who had been studying at a teachers college in the rural town of Ayotzinapa, had hijacked buses in hopes of reaching a demonstration, only to be intercepted by local police and never seen again.

Critics allege a coverup reaching to high levels of the Mexican government.

“I can’t believe that we are here, two years later, with the same pain, the same demands,” said protester Patricia Beltran, a 25-year-old student. “The government laughs at people’s pain, but we are here today to tell them that it is not only the parents of the 43, but all of Mexico that insists that this government do its job.”

At the head of the march through the heart of the capital were some of the missing students’ parents, many holding photos of their disappeared sons.

Mexico’s highest-profile human rights scandal of recent years, the case has cast a harsh glare on the nexus between corrupt officials and paramilitary gangs awash in cash from drug smuggling and other illicit activities. Critics say links between criminal networks and Mexican security services and politicians are embedded nationwide, not just in violence-ridden states like Guerrero, where the 43 were abducted.

The case has also become a rallying cry for those who see it as emblematic of the official culture of impunity and corruption that continue to undercut justice and accountability.

“We demand that the government doesn’t just wash its hands,” said Carlos Ruben Ortiz, 53, a businessman who was among the protesters rallying at the Angel of Independence monument, the start of the nearly four-mile march to the city’s central plaza. “We do not forget that the authorities are involved.”

The scandal has sparked two years of international condemnations and protests, including on the streets of Los Angeles. But authorities seem no closer to answering the central question: What happened to the 43 students?

The investigation is bogged down in conflicting theories, contradictory statements, incompatible hypotheses and reports of forced confessions, planted evidence and debate over what happened to the bodies.

Allegations of a government whitewash have battered the image of Peña Nieto, who took office in December 2012 amid broad hopes for judicial, police and economic reforms.

More than halfway through his six-year term, the president is facing historically low approval ratings. His ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party recently suffered a series of humiliating defeats in gubernatorial contests across the country.

According to the Mexican government’s official account — what a former attorney general called the “historic truth” — local police rounded up the students during a night of street violence and handed them over to members of the Guerreros Unidos drug cartel, who proceeded to kill them, incinerate their bodies in a remote garbage dump in the town of Cocula and toss their charred remains into a river.

Relatives of the students have long derided the official scenario as a “historic lie,” and in April the official account was shattered by a panel of international lawyers convened by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

The panel found that much of the government’s “evidence” had been provided by suspects who were tortured. The lawyers also cited a possible case of evidence tampering by government officials.

The findings lent weight to charges that the government was more interested in putting the case to rest than tracking down the guilty.

More than 130 people have been arrested, including the ex-mayor of Iguala, his wife, various local police officials and drug cartel members. One popular theory holds that the mayor ordered the students’ abduction because he feared their presence might disrupt a formal event organized by his wife.

The international investigators offered another potential motive: Unbeknownst to the students, one of the buses they commandeered may have been ferrying a clandestine load of heroin. Guerrero state is a key producer of the opium poppy used in production of heroin.

In addition, the international panel found that members of the federal police and military in the Iguala area knew what was happening as the incident unfolded, contradicting government assertions that only local officials were involved.

The panel, along with other experts, has also raised doubts about whether a fire sufficient to incinerate the remains of the 43 men had ever occurred at the garbage dump.

The Mexican attorney general’s office, which is officially in charge of the inquiry, has pulled back from its “historic truth” hypothesis.

The former chief investigator in the case resigned this month. Authorities said that the inquiry remains open, with police reportedly planning a new round of searches for the students’ remains.

“I want a better country for my kids, that’s why I’m here with them,” said Raquel Cisneros, 40, who marched in Monday’s protest along with her two children, ages 7 and 12. “I want them to live in a country without fear that someone will kill or disappear them.”

twitter: @mcdneville

Sanchez is a member of The Times’ Mexico City bureau. Times staff writer Tracy Wilkinson in Washington contributed to this report.

ALSO

Colombia peace deal officially ends Western Hemisphere’s longest war

Vietnam, the biggest hub for illegal rhino horn trafficking, has done little to stop it

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.