A Mexico City queer bar resists attacks with love and cumbia

Reporting from Mexico City — May 3 was like any other Friday night at La Cañita, a beach-themed bar and restaurant in a working-class neighborhood near downtown Mexico City.

A generously pierced and tattooed DJ mixed electronic music as bartenders splashed mezcal into shot glasses and popped open icy bottles of Corona. About two dozen of the club’s mostly queer clientele were crowded onto the tiny dance floor, laughing and flirting under red neon lights.

Then two men showed up, drunk and looking for trouble.

“Let’s get a hotel room,” one of them slurred at Dianna Torres, a writer and performer who owns the bar with her wife, musician Ali Gardoki.

“I’m married,” Torres replied. “And I’m a lesbian.”

She asked the men to leave. Instead, they began attacking, using fists and broken beer bottles as weapons. By the time they fled, six people were injured and the dance floor was covered in blood and shards of glass.

La Cañita, one of the only nightclubs run by and for queer women in this vast metropolis of 21 million people, had offered a rare safe space for the LGBTQ community since it opened in 2017.

Though rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Mexicans have expanded in recent years, discrimination is still widespread. Even in the liberal bastion of Mexico City, which in 2010 was the first jurisdiction in the nation to legalize same-sex unions, an anti-gay march a few years ago drew tens of thousands of people.

Torres and Gardoki had fought discrimination from neighbors just to open the bar in the first place. Now, as they accompanied their friends and staff to the hospital, they questioned whether it was time to close.

“We were all scared, we were all traumatized,” said Torres, who was tormented by nightmares about the attack.

But she and Gardoki ultimately agreed that La Cañita not only had a right to exist, it needed to exist. Too many people had come to depend on it.

The following night, they mopped up the blood and opened again, turning up the music and pulling benches out onto the sidewalk so smokers could lounge under the bar’s signature palm frond awning.

Early the next morning, after they had closed and gone home, Torres received a call from a panicked neighbor.

“Your bar is on fire,” he said.

Over the next few weeks, Torres and Gardoki would cycle through a mix of emotions — anger, anxiety, grief.

But they would ultimately decide to meet the violence with something else: love.

::

When Torres and Gardoki opened La Cañita, they weren’t trying to make a political statement. They just wanted a place where they could have a good time with friends.

“What I love most in life is to eat, drink and dance,” said Gardoki, who is 45 and hails from the Caribbean port city of Veracruz.

She was a teenager — a tomboy who lived for rock music — when she left conservative Veracruz for Mexico City in 1993. She quickly found her way to the center of the city’s legendary punk scene, playing guitar for Las Ultrasonicas, a beloved all-female band in the Riot Grrrl mold, and later touring the world with another popular group, the Kumbia Queers.

Gardoki, who wears her graying hair in a pompadour and favors suspenders, met Torres five years ago and fell for her immediately. A Spaniard who had settled in Mexico City after being invited there to give a talk, Torres is 38 and has tattoos on both sides of her partially shaved head. She calls herself an anarchist and a prison abolitionist and once wrote a book about sex and politics titled “Pornoterrorismo.”

Neither ever felt welcome in what Gardoki calls the “mainstream gay” bars of Zona Rosa, Mexico City’s version of West Hollywood. In those male-dominated spaces, where buff bodies and pop music reign, bouncers have been known to turn women away.

La Cañita, they decided, would be for everyone: gay, straight, transgender and those on the wide spectrum in between.

The concept for the bar, whose name means “little sugar cane,” was simple: There would be Veracruz-style ceviche and shrimp cocktails, a cash-only bar with cheap drinks and a constant stream of free cultural programming including lectures, photo exhibitions and live music.

They chose La Colonia Doctores, a blue-collar barrio that had a reputation for crime, because it was cheap and because Gardoki had lived there for years. Before they opened, they made an altar to Yemaya, the Yoruba goddess of the sea who is known as a protector of women, and vowed to always keep a candle burning for her.

Overnight, La Cañita became one of the most vibrant bars in the city, a gathering place for pioneers on the front lines of music, art and fashion. One night, a psychedelic cumbia band would have a crowd of young people twirling on the dance floor. The next, a DJ spinning deconstructed reggaeton would pack the bar with outrageously dressed club kids. It was crowded and sweaty and free.

A sticker in the club’s grimy bathroom read: “Death to the macho.” On the wall above the toilet somebody scrawled: “The future is trans.”

“La Cañita is a space for the weirdos, for the outcasts,” said Dolores La Bacha Black, a performer with a collection of bouffant wigs who hosted a weekly karaoke night.

“We live with constant violence,” La Bacha said, noting that Mexico ranks second in the world in killings of transgender people, with 68 slain last year. “This is a place for us to have a nice time without fear of machista violence.”

But that sense of sanctuary was fragile from the start.

Torres and Gardoki made an effort to win over residents, who they knew might be skeptical. They offered locals discounts on drinks and food and played Mexican folkloric music during lunch. La Cañita, built in a former barbershop, opened directly onto the street. When neighbors passed, Torres and Gardoki would smile from behind the bar and greet people by name or call out: “Hello, my love!”

But there was no question that La Cañita, with its beachy palm awning, stuck out.

Doctores, home to crumbling apartment buildings and a famed lucha libre wrestling stadium, is in many ways a vestige of Mexico City’s past. Dr. Andrade, the street where La Cañita opened, boasts an old-school newspaper and magazine vendor, an altar to the Virgin of Guadalupe and rundown flats crowded with extended families.

The area has only recently begun to feel the gentrification that has transformed the adjoining Roma neighborhood into a hipster’s paradise of boutique hotels, pricey cocktail lounges and techie co-working spaces.

The superintendent of the building where the La Cañita was located petitioned the city to shut it down. He told the city that it was operating in unsanitary conditions. But he told Torres and Gardoki that he didn’t want “weird” people congregating in the street. Children shouldn’t see that, he said.

The couple hired a lawyer to fight the eviction and won.

Then came the May 3 attack. Truthfully, it didn’t surprise them. Both had known queer people in the city who had endured violence.

The remarks of a police officer who responded to the attack didn’t surprise them either: “Why are you here anyway? Shouldn’t you be in Zona Rosa?”

“We’re not insects,” Torres fumed to herself. “We shouldn’t have to stay in a gay ghetto.”

The fire was what really crushed them. Firefighters managed to stop the flames before they spread to the inside of the bar. But the exterior was badly damaged and the beloved palm awning was gone.

Two men from the neighborhood were arrested and charged with assault, harassment and property damage. One of the defendants had previously served prison time. The pair were released while their trial is pending.

Torres, in particular, has felt torn about whether the couple should press for a prison sentence or try to seek a settlement with the men.

After the fire, she and Gardoki closed the bar for several weeks. One night, they called their regular patrons together for a meeting. Some showed up with mace, pepper spray and baseball bats.

The couple said they weren’t shutting down permanently or moving, as some of their relatives had urged. “We want to try to change our block,” Gardoki said.

The regulars who lived in the neighborhood organized a plan for daily safety patrols, while an online fundraiser netted more than $10,000 in donations. Torres and Gardoki installed a network of security cameras and opened the doors, once again lighting candles for Yemaya.

They decided to continue in part because they felt they had the city’s support.

Officials enrolled Torres and Gardoki in a federal protection program called the Mechanism to Protect Human Rights Defenders and Journalists. Under the program, police and human rights officials check on the bar multiple times a day.

But authorities did more than just offer protection. They thought about ways to regain community support for the bar. Together with Torres and Gardoki, they dreamed up a plan.

::

On a recent warm Sunday, as church bells rang and families sat down for the traditional afternoon lunch, the distinct beat of cumbia could be heard on the streets of Doctores.

A few days earlier, Torres and Gardoki had circulated a flier throughout the neighborhood explaining the attack and inviting residents to a block party — Cañita Fest. “We want to celebrate diversity and its contribution to the community life of this barrio,” the flier read.

The party was organized by the city as a “restorative measure” after the hate crime, said Geraldina Gonzalez de la Vega, president of the Council to Prevent and Eliminate Discrimination in Mexico City. “We want the message to be that we’re not going to tolerate this.”

The street in front of the bar was blocked off to traffic, and dozens of police stood guard. But with a lineup that included a mariba band and a voguing performance, the mood was jubilant — and defiant.

“I don’t want your catcalls, I want your respect!” rhymed a rapper from the state of Oaxaca named Mare Advertencia Lirika.

“Our revenge is to be happy,” she said to cheers. “It is joy.”

At first the crowd consisted mostly of La Cañita regulars — there were mohawks, pink and purple hair, and vendors selling an assortment of vinyl records and sex toys.

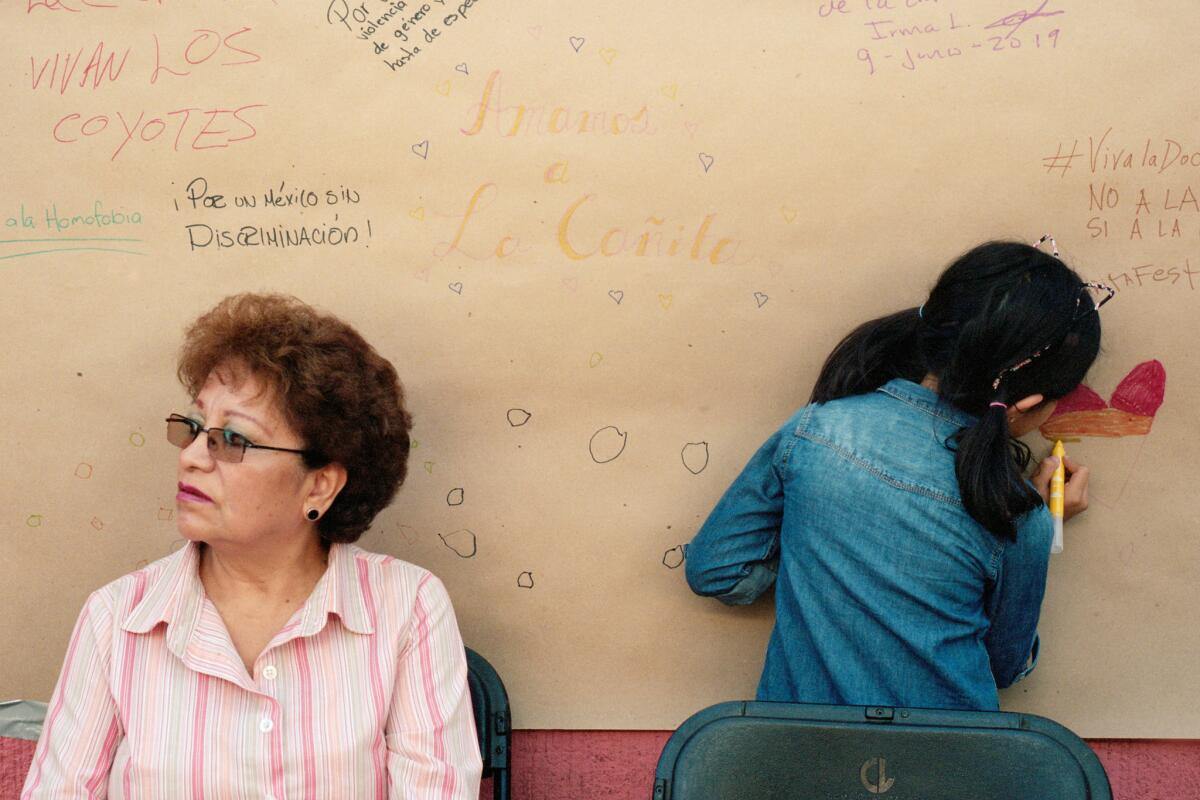

But as the day wore on, locals began spilling into the street. One of them was Marta Flores, a 63-year-old grandmother who reclined in a chair next to a poster where people were writing messages of solidarity to the the LGBTQ community.

“We are here to support them,” Flores said. “We are all equal.”

Then, as the sun began to set, turning the big sky hot pink, came the special surprise. It was the famed DJ known as Sonido la Changa — Torres had invited him.

The DJ, Ramón Rojo Villa, had grown up in Doctores, and in the 1960s had helped pioneer a style of music popular among Mexico’s working class known as cumbia sonidera.

“Que viva la Colonia Doctores!” he shouted at the beginning of his three-hour set, and that was all it took to fill the street with dancers.

As the music boomed and the day turned to night, everybody moved together: young queers, old queers, straight people of all ages from the neighborhood. Torres and Gardoki were racing around, making sure the party went on. But every now and then they slowed, looked out at what they had done, and started to dance too.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.