The long fight of the Mapuche people at times has turned violent. Pope Francis is about to get involved

Reporting from Santiago, Chile — Pope Francis will step into the middle of one of South America’s longest-running conflicts Wednesday when he visits the largely indigenous Araucania region of Chile.

In the century and a half since they were conquered by Chile’s military, the Mapuche people have continued to resist, demanding greater autonomy, legal recognition of their language and the return of their ancestral lands.

While the vast majority of the estimated 1.4 million Mapuche people are peaceful, some have at times employed violence in their fight.

In recent years, masked men have firebombed timber trucks and land owned by non-Mapuche people that they say is rightfully theirs, sometimes leaving pamphlets calling for Mapuche rights. They set fire to more than two dozen churches in 2016 and 2017, according to the Chilean prosecutor’s office.

Three more churches were firebombed in Chile’s capital, Santiago, on Friday. Leaflets dropped at the scene criticized the upcoming visit of Francis and called for a “free” Mapuche nation. No one took responsibility for the attacks, and authorities said they were unsure whether Mapuche activists were to blame.

Many view the pope’s visit to Temuco, the capital of Araucania, as a sign of support for the tribe and its struggles. Francis has expressed solidarity with other indigenous groups. While visiting Bolivia in 2015, Francis apologized for the “grave sins” committed against native communities by the Roman Catholic Church during colonial times. The pope’s familiarity with the region — he was born in Argentina — may also help explain his decision to visit Mapuche lands.

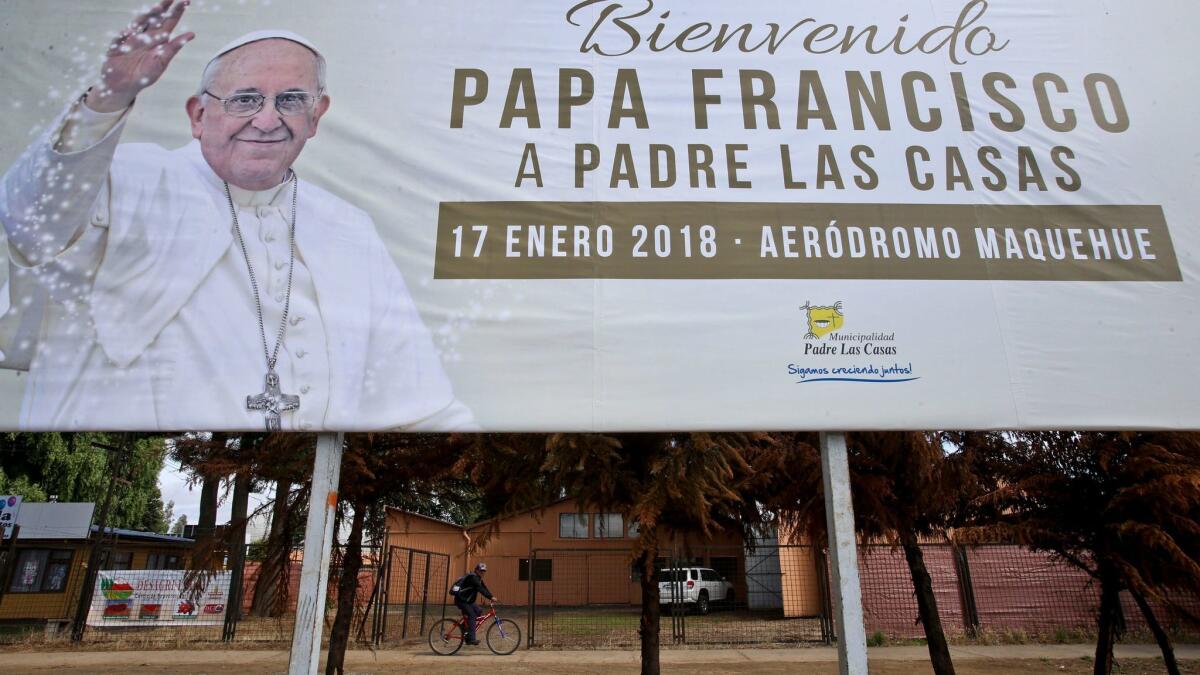

The pope will touch down in Temuco on Wednesday, celebrate Mass at the Maquehue air base and have lunch with a number of residents handpicked by local church leaders. Protests are expected outside the air base, which was built on land taken from the Mapuche.

While some in Chile complain about the Mapuche’s tactics, many are sympathetic to their plight.

“These acts of force or political violence such as burning churches or trucks or even homes reflects that there is an open wound,” said Jesuit priest Carlos Bresciani, who has lived for 15 years near Tirua, a traditionally Mapuche village.

The Mapuche famously resisted Spanish conquest during colonial times, using guerrilla warfare tactics to evade European fighters seeking to lay claim to their historic homeland in what is now Chile and Argentina. They eventually signed a treaty with the Spanish, becoming the first and only South American indigenous group whose sovereignty and autonomy the Spanish legally recognized.

Because the Mapuche were not conquered, the Catholic Church had little success converting them. Even today, it is rare to see churches in Mapuche communities, which are scattered from the Andes mountains to the Pacific coast in Chile, as well as in parts of western Argentina.

After Chilean independence in 1818, the tribe fended off soldiers for decades. In the 1860s, the military won. The Mapuche’s ancestral lands shrunk from 24 million acres to 1.2 million as the government signed over property to the military, arriving European immigrants and the Catholic Church.

How far the pope goes in expressing support for the Mapuche will be closely watched. The tribe’s leaders and Chilean officials have both said they hope he can help moderate the conflict, which experts worry could worsen.

“It’s a sore spot that could potentially grow,” said Tom Dillehay, an anthropologist at Vanderbilt University who has studied the tribe.

The possibility of the Mapuche taking up arms like the Zapatista indigenous group in southern Mexico is not out of the question, Dillehay said.

In certain aspects, life has improved in recent years for the Mapuche, who make up about 8% of Chile’s population.

Since the return of democracy to Chile in 1990, successive governments have purchased land to give back to the Mapuche. Scholarships have been created for Mapuche students. The government also created the National Corporation for Indigenous Development, which addresses issues related to Chile’s indigenous people.

But many tribe members believe the changes are not enough. The Araucania region, where many Mapuche eke out livings farming subsistence crops of potatoes and wheat, is the poorest in Chile. And Mapuche complain of abuse at the hands of authorities.

This month, some Mapuche clashed with security forces at a protest marking the 10-year anniversary of the killing of an activist by police.

“Like indigenous groups everywhere, they are subject to racism and discrimination,” Dillehay said. “They’re a force to be dealt with. Chile’s got to be careful.”

Twitter: @katelinthicum

Times staff writer Linthicum reported from Mexico City and special correspondent Poblete from Santiago.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.