Not screening in Mexico: Its own new golden age of film

Reporting from Mexico City — “The Untamed” (“La Región Salvaje”), a Mexican thriller about sex, lies and a mysterious monster, won the Silver Lion directing award for filmmaker Amat Escalante when it premiered at the 2016 Venice International Film Festival. Three years earlier, Escalante won the director prize at the Cannes Film Festival for his graphic drug trafficking drama “Heli.”

It’s no wonder “The Untamed” was quickly picked up for distribution in the U.S. and across Europe. Everywhere but Mexico.

Mexico’s film scene is booming, with a record 175 films made here last year. And in Hollywood, Mexican directors seem to be a key to success at the Oscars. Guillermo del Toro’s “The Shape of Water” is the odds-on favorite to win the Academy Award for directing on Sunday, and three of the last four directing Oscars went to Mexican filmmakers — Alfonso Cuarón in 2014 (“Gravity”) and Alejandro Iñárritu in 2015 (“Birdman”) and again in 2016 (“The Revenant”).

But despite an increase in state funding that has nurtured a new golden age of Mexican cinema, with Mexican films winning more than 100 international awards in 2017, domestic distribution and exhibition has not kept pace with production. Which means that films made in Mexico often aren’t seen in Mexican movie theaters.

Filmmakers and government officials say the country’s two major theater chains are reluctant to give space to new Mexican films when Hollywood movies account for the vast majority of ticket sales. Last year, the 20 top-grossing movies in Mexico were American-made.

Only after public pressure, including a chiding on Twitter by Del Toro and Cuarón, did “The Untamed” finally open in Mexican theaters last month — nearly two years after its world premiere. The film’s run didn’t last long, in part, Escalante thinks, because Mexicans had already been able to watch it for months on iTunes and Amazon.

Escalante says he and other prominent filmmakers have met with top government officials in recent months to see what can be done to speed up the release of Mexican movies inside the country.

“We feel the Mexican audience shouldn’t have to wait a year and a half to see a Mexican film,” Escalante says.

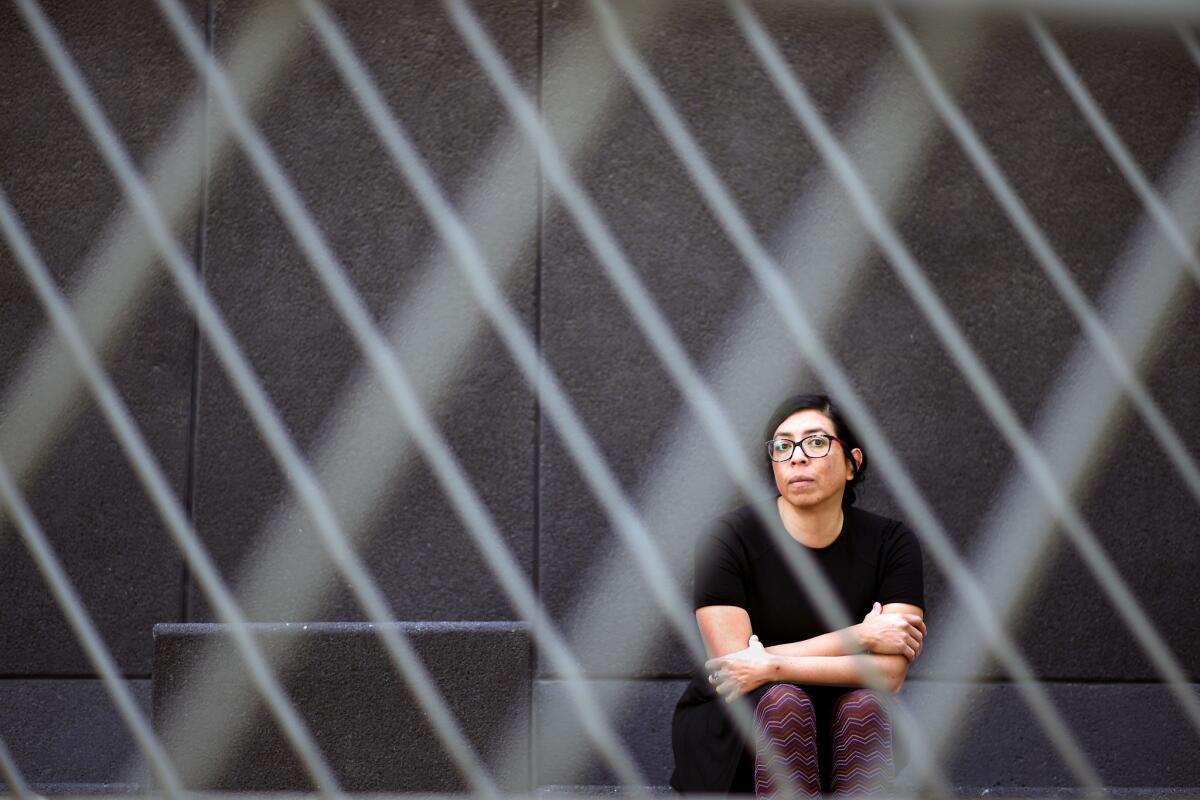

“It’s an enormous contradiction,” says documentary filmmaker Tatiana Huezo, whose films “Tempestad” and “The Tiniest Place” won prizes at festivals around the world and screened in Mexico.

“We’re making a huge number of films, but so few are shown here,” she says. “We can’t see our own stories.”

It’s an enormous contradiction. We’re making a huge number of films, but so few are shown here we can’t see our own stories.

— Tatiana Huezo, filmmaker

Today’s burst of moviemaking calls to mind Mexico’s first golden age of cinema, in the 1930s and 1940s, when stars such as Cantinflas, María Félix and Pedro Infante put Mexico on the map as one of the world’s top producers of film.

The industry began to fade in the 1950s, overtaken by Hollywood imports and the government’s clumsy efforts to intervene in the film business, which included imposing ticket price controls and buying up major studios and movie theaters. By the mid-1990s, fewer than 10 films were being made each year, in large part because there was little access to private financing.

The climate was so inhospitable that budding filmmakers such as Del Toro, Iñárritu and Cuarón had little choice but to cross the border to chase their dreams.

Life for filmmakers in Mexico began to improve about 15 years ago, when the government upped its support. The Mexican Institute for Cinematography, known as IMCINE, now gives away around $44 million a year for film productions — more than 10 times what it was handing out in the 1990s. Well over half the films produced in Mexico last year were financed or co-financed by the government.

ALSO: Beyond Mexico’s Oscar darlings, here are three Mexican filmmakers you need to know

Government assistance allows for more risk-taking, says director Alonso Ruizpalacios, whose new heist film, “Museum,” starring Gael García Bernal, was partially funded by the government and won the screenplay prize last week at the Berlin Film Festival.

“The director almost always has the final cut in Mexico,” says Ruizpalacios, who co-wrote “Museum.” “The filmmakers I know in Hollywood really envy that.”

In recent years, Ruizpalacios has dabbled in Hollywood. He directed the first episode of the upcoming Starz show “Vida” and is preparing to direct two episodes for the fourth season of the hit Netflix show “Narcos.”

“It pays the rent,” he says of the Hollywood gigs. “But I have to come back here to do my own projects to have real control.”

Another upshot for directors working outside of Hollywood is freedom from “political correctness,” says Escalante, whose “The Untamed” features explicit sex scenes involving an octopus-like alien monster and whose 2013 “Heli,” about an autoworker whose life is upended by organized crime, featured graphic scenes of torture.

“There’s this carefulness and fear of offending in Hollywood,” he says. “I wouldn’t be able to make these movies in the U.S.”

Filmmakers say they are also able to portray Mexico with more complexity than they would in Hollywood, which tends to tell two kinds of Mexico stories: immigration dramas or bloody drug war thrillers.

Take the powerful but subdued documentary “Devil’s Freedom” by Everardo González, which features painful testimonies by both victims and perpetrators of Mexico’s violence. The twist is that all of those interviewed are wearing masks, giving an eerie sense that anyone in the country might be capable of being victimized or victimizing. Huezo’s 2016 film “Tempestad” employs a similar technique. While it’s focused on two women’s encounters with human trafficking, the camera lingers on scenes of the Mexican countryside and close-ups of random Mexican faces instead of showing actual violence.

At a time when Mexico is recording more homicides than at any point in that last two decades, that brutal honesty may be hard for some Mexican moviegoers to watch.

“Sometimes Mexican audiences don’t want to go to the cinema to see a mirror of what they see in the streets,” says producer Nicolás Celis, who has helped make several of the country’s recent award-winning films, including “The Untamed.” Celis complains that movie theaters don’t expect audiences to go see Mexican films, so they are frequently short-changed, often scheduling screenings in the middle of the day, if at all.

“I’m not used to presenting our films in a healthy market,” he says. “I’m used to having a film in just a few theaters, and then they suddenly change the release date.”

Filmmakers can apply for public subsidies for publicity and other support once their films are finished. But competition is fierce.

Many of the films being made in Mexico also struggle to find an audience internationally. In the U.S. there’s a scarcity of distribution companies focused on bringing Spanish-language films to U.S. audiences.

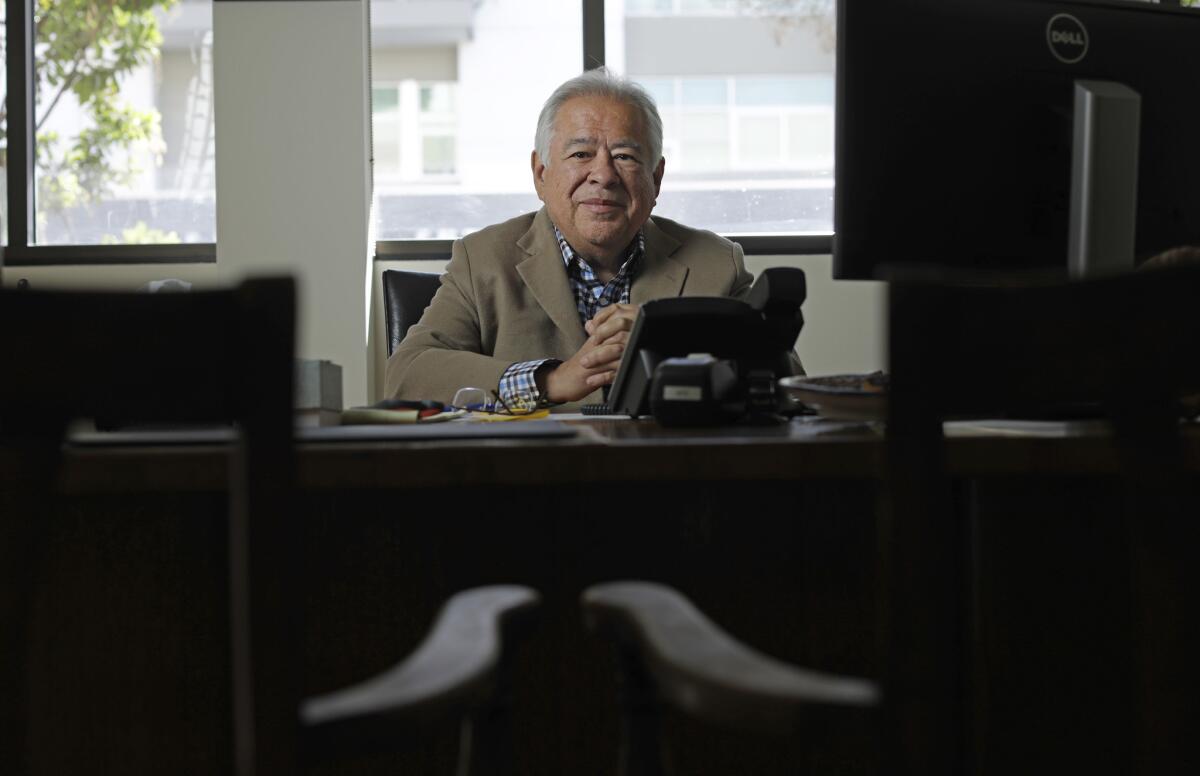

Even “Selena” producer Moctesuma Esparza, whose growing California theater chain Maya Cinemas programs the occasional Mexican film among first-run blockbusters, says he rarely sees modern Mexican movies. While two of his Central Valley locations are currently showing Marco Polo Constandse’s “La Boda de Valentina,” he’d like to screen more Mexican films. But few, he says, are being distributed.

“I’m not that familiar with Mexican cinema anymore,” says Esparza, who grew up watching Mexican films from the first golden age. “If I don’t go to the film festivals, then I don’t get to see them.”

Although it’s still hard to make a profit on a film in Mexico, there are signs that things are improving. Last year, four Mexican films grossed more than $5 million domestically each, according to IMCINE.

But there need to be better avenues for films to reach audiences, Mexican officials say, including more support for independent theaters and public screenings.

“It’s crazy that a movie can win in Venice but not be screened here,” says Consuelo Sáizar, who served as president of Mexico’s National Council for Culture and the Arts from 2009 to 2012.

For now, many moviegoers resort to other methods to see current Mexican films.

Ana Cristina Chavez, 27, a teacher who was waiting in line to buy tickets at a theater on the south side of Mexico City on a recent weekend, said she would like to watch more films made by her compatriots, but they just aren’t available in many theaters.

“It’s frustrating,” she said. “I end up watching a lot online.”

ALSO

Review: Amat Escalante’s remarkable erotic horror of Mexico’s ‘The Untamed’ is unnerving

Guillermo del Toro’s ‘The Shape of Water’ is the true wonder of awards season

Twitter: @katelinthicum

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.