The Week Ahead: Suu Kyi sojourn, Thatcher farewell, Italy adrift

Testing the waters for a revitalized Asian alliance

Now through Saturday, April 20: Democracy activist Aung San Suu Kyi’s visit to Japan this week is purportedly unofficial, but the Nobel Peace Prize laureate probably has more clout than any Myanmar government delegation in charting a course for repairing business and social ties between Tokyo and her homeland.

Japan’s investments in Myanmar after half a century of military dictatorship pale in comparison with the billions being pumped in by China, Thailand and India. But Tokyo has forgiven $3 billion in debt racked up by the country also known as Burma, clearing the way for easier credit and joint projects that will generate energy, rebuild infrastructure and recover Myanmar’s role a a major rice exporter.

Business leaders from some of Japan’s most prestigious manufacturers, including Toyota and Hitachi, visited Myanmar two months ago to explore prospects for collaboration and improved trade, after which Tokyo pledged $200 million for a special economic zone being built south of Yangon.

As the voice of moral authority in Myanmar, Suu Kyi, who began her visit Saturday, is expected to evaluate potential projects for the benefits they could offer the recovering country versus the costs. Myanmar last year suspended construction of the Myitsone Dam, a massive hydroelectric project backed by China, because it would have flooded the spiritual homeland of the Kachin minority and left thousands homeless.

Remembering Margaret Thatcher and her mark on the world

Wednesday, April 17: World leaders gather at London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral on Wednesday for the most elaborate funeral in Britain in more than a decade to pay final respects to “Iron Lady” Margaret Thatcher.

The controversial conservative who was Britain’s first and only female prime minister died April 8 after a stroke at age 87, unleashing a conflicting cascade of accolades and criticism reminiscent of the divisive views that surrounded her 11-year leadership. A strong police presence is planned to guard against disruptions by dissident Irish republicans, leftist protesters and others angered by her transformation of Britain’s postwar welfare state into a free-market economy.

Queen Elizabeth II and her husband, the Duke of Edinburgh, will be in attendance -- the queen’s first presence at a politician’s rites since Sir Winston Churchill died in 1965. All surviving British prime ministers, Cabinet members and U.S. presidents have been invited to be among the official representatives of more than 200 nations, territories and international organizations. One leader pointedly not invited was Argentine President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, whose country provoked a short 1982 war with Britain over the Falkland Islands.

Thatcher’s coffin will be carried through the streets of central London from the Palace of Westminster, where the houses of Parliament meet, to St. Paul’s for the service, expected to draw more than 2,000 invited dignitaries, politicians, friends, family and cultural figures. A private cremation will follow.

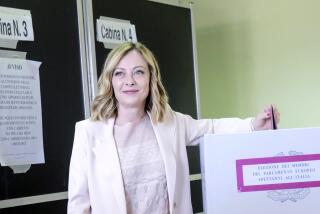

A contentious and elusive search for leadership in Italy

Thursday, April 18: Small wonder that some in Italy refer to their election law as “the pigsty.”

The legal guidance for choosing upper and lower house representatives and having the fractious political party leaders negotiate a governing coalition is so complicated and fraught with idiosyncrasies that it can result in a mess like the one prevailing today.

Italians roiled by a persistent recession and demands for austerity from Eurozone colleagues voted Feb. 24-25, splitting their support among three irreconcilable political platforms: the center-left led by former Communist Pier Luigi Bersani, the center-right led by scandal-plagued former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, and potty-mouth comedian-turned-populist Beppe Grillo.

Grillo refuses to form a government with either established party, and Bersani and Berlusconi have failed in their repeated attempts to bridge their yawning ideological gap and agree on a grand coalition. In most parliamentary democracies, it would fall to the president to name a government of technocrats or call a new election, as it does in Italy except during the head of state’s last weeks in office. Italian President Giorgio Napolitano’s seven-year stint ends May 15.

The parliamentary procedures for choosing a president are required by law to get underway on Thursday, so the political parties have turned their attention from the failed task of deciding a government to horse-trading their way to a consensus candidate to succeed Napolitano.

A two-thirds majority of Parliament members is needed to elect a president, or a simple majority if the first three ballots fail. Bersani’s faction is expected to eventually pull together a bare majority.

First order of business for the new head of state: Calling new parliamentary elections, perhaps as soon as June, more likely later, but not before the summer vacation season concludes or a low turnout would result in another inconclusive vote. Most bets are on October, despite the risk of eight months of rudderless administration deepening the recession and delaying growth-stimulating reform.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.