Brazil’s evangelical churches rewrite the rules of politics

SAO PAULO, Brazil — As euphoric rock music played, dozens of men in suits swarmed the aisles with hand-held credit card machines to take donations from the faithful.

The pastor smiled at the crowd in the downtown headquarters of the mega-church and, as cameras rolled, belted out: “We all voted already, right? Who voted today?”

In the spotlight, he made no mention of whom he hoped his flock had cast ballots for. But for most in the crowd, and those watching the election for the mayor of Latin America’s largest city, it was clear which candidate Brazil’s increasingly influential evangelical churches were throwing their weight behind.

Television personality Celso Russomanno took Brazil’s political establishment by surprise when he shot to the top of the polls in the run-up to the election. Although he is Roman Catholic, his relatively new Brazilian Republican Party is backed by the powerful Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus, or Universal Church of the Kingdom of God.

In the world’s largest Catholic country, a group of well-organized evangelical churches is rewriting the rules of politics here. In the process, the evangelicals have dismayed Brazilians uneasy with such blatant mixing of religion and politics.

Amid a surge in Latin America in recent years, more than 20% of Brazilians are now evangelical Christian. Followers make up one of the largest voting blocs in Congress, and use their money, influence and media power to press a small set of socially conservative issues, as well as to maintain favorable conditions for their often very profitable enterprises.

“They don’t yet have quite as unified an agenda as the evangelical movement in the U.S.,” said David Fleischer, a political scientist at the University of Brasilia. “But they are growing, and are far more effective than the Catholic Church at convincing people to vote one way or another.”

Since colonial times, the Roman Catholic Church has been the dominant religious force in Brazil, though in practice it has often been mixed with indigenous and African traditions. Still, not only did the constitution establish separation of church and state, but voters and the church also tend to abhor any direct religious endorsements in elections.

Russomanno’s position in the polls shocked the elites into action here and, after attacks from all sides — from the left, the right, the Catholic Church — he ended up finishing third.

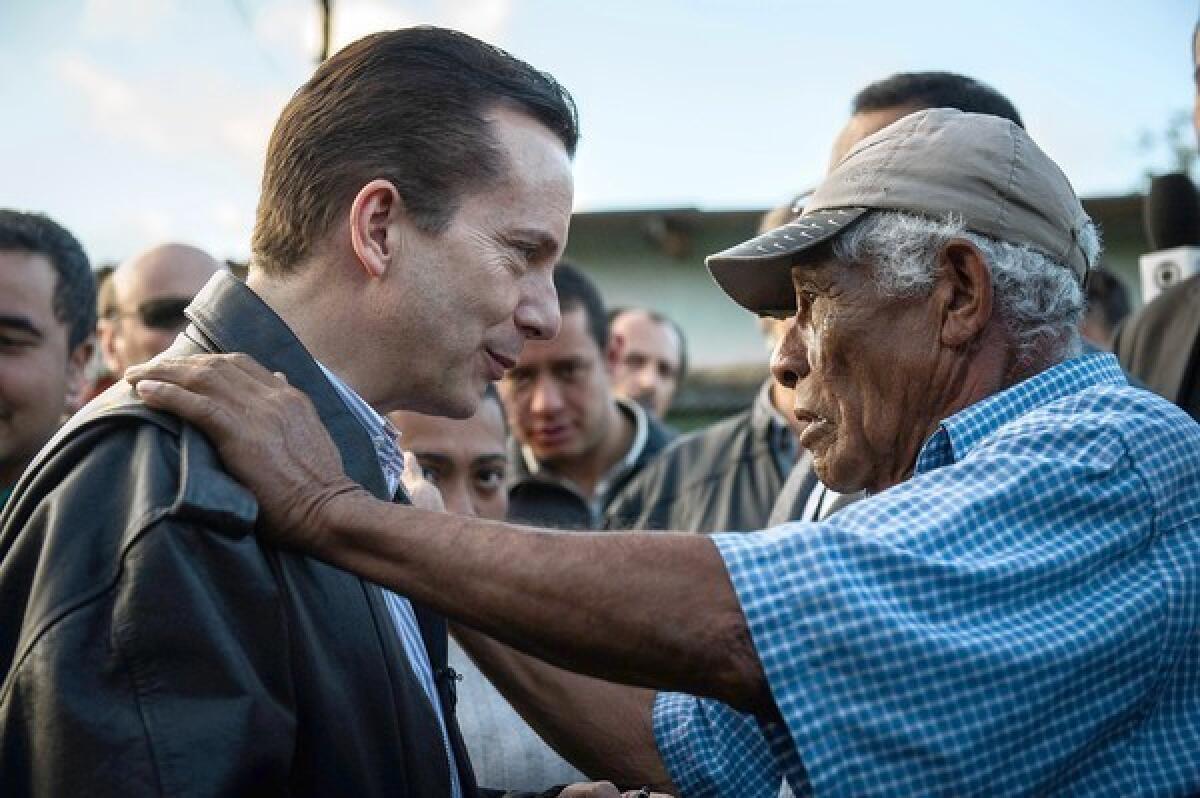

But his movement made its mark. The candidate from the ruling left-leaning Workers’ Party, Fernando Haddad, immediately sought his backing in the runoff Sunday.

Nationally, President Dilma Rousseff maintains an uneasy alliance with the evangelical bloc, which makes up about 10% of the Brazilian equivalent of the House of Representatives. The group flexed its political muscle in a big way last year when it killed Rousseff’s plan to supply Brazilian schools with anti-homophobia educational materials.

On the Friday before the first round of voting early this month, a group of artistic and cultural activists mounted a large protest against Russomanno’s sudden rise, using social media to organize a group of rock, funk, hip-hop and traditional Brazilian forro concerts. Some revelers wore shirts proclaiming “Not Serra, not Russomanno,” with Jose Serra, the center-right candidate, portrayed as Mr. Burns, the character on “The Simpsons” (he does bear a resemblance), and Russomanno as fellow character Ned Flanders.

But evangelical politics isn’t just about traditional conservative issues such as morality or abortion, which is illegal in Brazil. Elected officials at the local level also push for favorable zoning and municipal rulings that allow them to easily develop new churches. And then there is the more subtle use of political power, Fleischer said.

“The larger churches face frequent accusations of income tax evasion, money laundering and all sorts of other fraudulent activity. Edir Macedo, the head of Igreja Universal, also owns the second-largest TV network in the country, which should technically be unconstitutional,” Fleischer said, because he is a religious figure operating on public airwaves. “But the state looks the other way.”

Macedo’s Universal Church has branches in Africa and is successful throughout Latin America. In California, the local branches, which attract large numbers of Spanish speakers, are often recognizable by the slogan “Pare de sufrir,” or “Stop suffering,” a subtle dig at Catholic cultural traditions.

In Sao Paulo, many were puzzled as to why Russomanno denied he was backed by the evangelicals. Macedo also denied strong links, despite his pastors calling on worshipers to vote for him and a blog he published (anonymously) listing reasons to vote for him.

“I don’t like who is paying” for Russomanno, Sueli Machado, a 65-year-old retiree, said after voting in Penha, a poor neighborhood on the outskirts of Sao Paulo. “I don’t have anything against any religion, but the men who run those churches are millionaires rich off of donations. If he can’t admit they are behind him, how can I trust him?”

Later that week in Penha, a Universal Church pastor gave a small congregation bars of green soap that would “wash not just your body, but your soul.” Then he led the screaming crowd in a ceremony to expel demons from a middle-aged woman, who writhed at his touch.

Before ending the ceremony, he asked the parishioners to give themselves a round of applause: “Look at all the people we got voted onto the City Council!”

Bevins is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.