In Venezuela, U.S.-Guaido strategy flops again: Is this working?

Reporting from Caracas, Venezuela — In a moment of high drama, opposition leader Juan Guaido stood outside the La Carlota military air base here at sunrise Tuesday with an entourage including defecting soldiers and proclaimed the “final phase” of “Operation Liberty.”

By noon the would-be rebellion was effectively quashed, marking the latest high-profile failure of Guaido and his U.S. backers to enlist military support to oust the government of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro.

The armed forces high command — the traditional arbiter of power here — denounced what it called an attempted “coup” and the opposition’s latest botched plot.

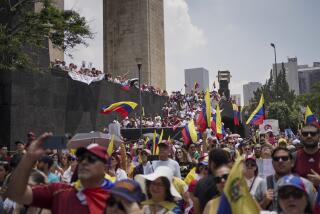

Guaido’s unsuccessful push to win the generals’ backing sparked two days of street battles between protesters and security services, leaving at least five dead, scores injured and hundreds jailed. By week’s end, the smoke and tear gas had cleared and an aura of normality returned to the capital.

The turmoil and cloak-and-dagger maneuverings here and in Washington did not outwardly reshape this beleaguered nation’s underlying power contours: Maduro remains in office and Guaido is still the self-proclaimed interim president of a parallel government controlling no territory or ministries.

Days later, there is still little clarity about what went wrong during what was touted by Guaido as a decisive moment in the history of this once-wealthy and oil-rich South American nation, battered by years of political, social and economic upheaval.

The events unfolded more than three months after Guaido, 35, an opposition legislator and industrial engineer, assumed the mantle of “interim president,” labeling Maduro — who won re-election last year in widely discredited elections -- a “usurper” and calling on the military to switch sides. The failed plot last week took place more than two months after Guaido, also with Washington’s backing, incorrectly predicted that Venezuelan armed forces would turn against Maduro and allow truckloads of mostly U.S.-provided humanitarian aid into Venezuela.

“The apparent unity of the [Venezuelan] upper command despite three visible calls by Guaido to abandon Maduro since January raises significant questions about the reasons for his [Guaido’s] apparent overconfidence,” said Jennifer McCoy, a Latin American expert at Georgia State University.

But both the opposition and its U.S. backers insist that the still-shadowy episode last week had indeed broken the generals’ heretofore seemingly resolute support for Maduro.

“The fissure that was opened on April 30 will become a chasm that will end up breaking the dike,” predicted Leopoldo Lopez, Guaido’s political mentor, sprung from house arrest on April 30, apparently by defectors within the security services, as part of the aborted uprising. “What began on April 30 is an irreversible process,” said Lopez, speaking from the gates of the Spanish Embassy here, where he has taken refuge.

Backing those sentiments were senior Washington officials, including Elliott Abrams, the Trump administration’s special envoy to Venezuela.

“He [Maduro] has to know that the high command isn’t truly loyal, and they want a change,” Abrams, speaking Spanish, told an interviewer from VPItv, a Venezuelan online outlet.

Of course, this may be U.S. and opposition spin — insinuating divided loyalties in the ranks is a time-honored destabilization technique for fomenting discord in a targeted government.

“There is no evidence of deep rifts within the [Venezuelan] armed forces,” said David Smilde, a Venezuela expert at Tulane University and the Washington Office on Latin America, a nonprofit research and advocacy group. “If there were, Maduro would quickly act upon it.”

But the Venezuelan commanders racing to display a steadfast wall of allegiance to Maduro in the aftermath of last week’s reports of treachery could also be dissembling.

Venezuelan Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino Lopez, who was among three top officials publicly named by Washington as accomplices of the opposition, seemed to confirm that Guaido’s representatives had approached him — though he mocked their offer, without providing details.

“They think they can buy us,” Padrino told troops gathered at the Fuerte Tiuna military base, where he appeared alongside Maduro in a nationally televised event designed to showcase the armed forces’ fidelity. “As if we were mercenaries. … They think they can break military honor.”

Some have speculated that Padrino may have been engaged in a devious double game: Listening to opposition feelers in a bid to smoke out who inside the government was implicated in the plot.That would imply that Guaido’s operatives were duped and misread the situation, possibly endangering their own covert collaborators.

The opposition and U.S. officials alleged that a tentative agreement had been reached with Venezuela’s top brass, including Padrino, that would have seen Maduro leave the country. Guaido would then preside over a “national unity” interim government, including top Maduro loyalists, according to U.S. and opposition officials. Venezuela’s supreme court was supposed to sign off on the matter.

It didn’t turn out that way. The deal ultimately broke down, the opposition and its Washington backers acknowledge, for reasons that remain murky.

According to Abrams, Maduro and his Cuban advisors may have gotten wind of the plot a day or two before it was supposed to launch into an operational phase, forcing Guaido to move prematurely on April 30 and stage his high-profile media event outside the La Carlota air base. The point of that gathering seemed largely symbolic, however: Guaido appeared to anticipate a kind of cascading, domino effect of uprisings that never materialized.

In Washington, meanwhile, Abrams and others seemed caught off guard by Guaido’s moves, suggesting a lack of coordination and communication.

A 15-point, written “national unity” deal between the opposition and government insiders envisioned a transitional administration, with Guaido as interim president but allowing the armed forces high command, the country’s supreme court justices and other government officials to retain their positions, according to Abrams. New elections would have been convened within 12 months, Abrams told the Venezuelan online TV network.

Despite its latest setback, the opposition does appear to have flipped one high-ranking government insider: Gen. Manuel Ricardo Cristopher Figuera, a former Maduro confidant and ex-head of the country’s Bolivarian National Intelligence Service, known as SEBIN, its Spanish acronym.

In the fallout from last week’s machinations, Maduro dismissed Figuera, a longtime aide-de-camp to the late President Hugo Chavez, Maduro’s political mentor. Figuera has dropped out of site among rumors that he left the country.

A statement attributed to the former intelligence chief circulating on various websites denounced systematic “corruption” and hinted at profound schisms in Venezuela’s leadership.

“I discovered that many people in your confidence were negotiating behind your back,” Figuera wrote in the attributed statement, addressing his “commander in chief,” Maduro. “But they weren’t negotiating for the well-being of the country. They were doing it for their own and petty interests.”

Whether Figuera’s asserted letter was genuine or part of an intelligence effort to discredit Maduro’s government remained unclear, as was much of the fallout from last week’s failed opposition effort.

--Special correspondent Mogollon reported from Caracas and Times staff writer McDonnell from Mexico City. Special correspondent Chris Kraul in Bogota, Colombia, contributed to this report.

In Venezuela, clashes continue as protesters for and against Maduro fill the streets »

Twitter: @PmcdonnellLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.