‘It’s just barbarity’: Togo’s political prisoners describe torture in police custody

Reporting from Lome, Togo — Imourane Issa braced himself for the next crack of a whip across his back. His head felt heavy on the concrete floor. He estimated that he was one of about two dozen men being tortured in the garage. The lone woman lay shaking in a puddle of her own urine.

There in the the headquarters of Togo’s secret police — the notorious Research and Intelligence Service — the captives were beaten, waterboarded and forced to kneel and neigh like horses.

“Some were hit with electrical cords, some of them had their heads cracked open,” Issa said. “They were forced to take their clothes off to wipe off their own blood.”

Finally, they were all herded into the backs of pickup trucks and driven away.

It was August 20, 2017, one day after the first in a series of massive nationwide protests calling for term limits aimed at ending the presidency of Faure Gnassingbe, whose family has ruled Togo for more than 50 years.

His government has been fighting back, using the military and police to suppress uprisings and help stifle efforts by opposition legislators to make constitutional changes that would block him from running in the next election, scheduled for 2020.

Since the protests started last year, drawing tens of thousands of people into the streets, hundreds have been detained and several shot dead as soldiers have resorted to tear gas, live ammunition and mass arrests.

“It’s a military regime with a civilian figurehead at the top effectively doing their business for them,” said Jeffrey Smith, the founder of Vanguard Africa, a Washington nonprofit that works with Togolese pro-democracy activists. Gnassingbe “is putting a patina of legitimacy on an otherwise illegitimate military regime,” he said.

The Gnassingbe family rule started with the military. Gnassingbe Eyadema took power in a 1967 coup — seven years after independence from France — and ruled the tiny West African nation until his death in 2005.

His son immediately took over the presidency and two months later won an election amid violent rioting. Hundreds of people died — most of them killed in their homes by government authorities, according to the United Nations. Faure Gnassingbe prevailed again in controversial elections in 2010 and 2015.

Even on an impoverished continent where corruption and abuse of power are rampant, Togo under the Gnassingbe family has stood out for its human rights violations, slow economic development and institutional breakdown.

Human rights officials describe a culture of impunity under the current president that is reinforced by the continuing lack of justice or accountability for the killings by security forces when he first took office.

The demonstrations last year were inspired in part by the fall that January of Gambian dictator Yahya Jammeh, who had ruled for 22 years before he was defeated in an election and, after a month of refusing to step down, left the country.

The protests were organized by an opposition coalition and the Pan-African National Party, which was formed in 2014 and later gained popularity for its promises to investigate corruption and promote democracy. When torture victims are forced to kneel and neigh, it’s because the party logo features a horse.

Government officials have not responded to multiple attempts to ask them about unrest over the last year or the use of torture and other tactics to suppress it.

Among those arrested last year in the capital, Lome, was the party’s secretary-general, Dr. Kossi Sama, who said he was whipped and beaten by secret police before being sent to prison. He was found guilty of rebellion, among other charges, and spent three months in detention before being released in November, a few days after 42 other political prisoners were freed as a condition for holding a dialogue between Gnassingbe and the opposition.

“It’s just barbarity,” Sama said. “They’re not asking questions, they’re just accusing us of creating a political party that’s against Faure [Gnassingbe]. That’s what they’re punishing us for, just for being against Faure.”

Many in the capital said they no longer trust their neighbors, taxi drivers and local shopkeepers for fear of being targeted as troublemakers. Surveillance is not sophisticated in Togo, but those who oppose the government live in fear of being overheard.

Still, the opposition remains undeterred and in some ways emboldened by the crackdown.

“This is what happens to heroes. They sometimes face challenges like this because they tell the truth,” said Zoulkadou Alfa Yaya, a 25-year-old university student. “Repression, torture, that’s what we’re trying to change. Now that repression is increasing, so is resistance against it.”

He didn’t grow up in a political family. But he came to blame the government for many of the country’s problems — crumbling infrastructure, long lines at the hospital, poverty — and started attending opposition party meetings.

Party leaders promised to weed out corrupt public officials and put Togo back in the hands of the people, and Yaya became convinced that the only path forward were elections to drive the current administration out of power.

“In Togo, even if you don’t do politics, politics do you,” he said. “I prefer that I do it before it does me.”

Before one protest march last year, he woke up early, dressed in red and left his phone at home to avoid having it searched by the police. When soldiers began firing tear gas into crowds, he took cover in a stranger’s home for several hours before attempting to avoid the authorities and make his way home.

Instead, he accidentally walked directly into a group of soldiers and was arrested and charged with destruction of public property.

Tried in a group of 27 people, he was among 16 found guilty. He spent three months at Lome’s central prison, a compound of run-down buildings where many political protesters wound up last year alongside murderers, rapists and other violent convicts already there.

Outside the main entrance, a portrait of Nelson Mandela is painted on the walls, the words “prison is a school” scrawled below. During visiting hours, family and friends jockey for the best position to pass food and messages through bars to throngs of half-dressed inmates.

In photographs provided to The Times by an inmate, cells are so crowded that prisoners sleep on top of one another. Several former prisoners described cell floors littered with feces and urine and said that inmates are denied access to food and medical care.

Among the inmates is Messenth Kokodoko, a member of the opposition civil society movement Togo Debout, or Togo Stand Up.

In an interview at the prison in March, Kokodoko said officers from the secret police tortured him for 12 days, demanding information about the movement and whether it intended to overthrow the president. He said the interrogators whipped him until he bled through his shirt, then dragged him outside.

“One would stand in front of me and the other behind me, with his gun on my head,” he said. “I thought I was going to die.”

When another member of the movement, Joseph Eza, tried to visit Kokodoko to deliver food and find out more about his detention, police followed Eza home and arrested him too.

“My children are traumatized,” Eza said. “They saw all this happen and didn’t know what was going on.”

He too remains in prison.

Issa, the man who was whipped by secret police, also wound up there. Convicted of rebellion and destruction of public property, he served a three-month sentence, sharing a cell with up to 80 people.

He was forced to pay simply to lie down or take a shower. Beatings were common, and some prisoners were denied treatment for tuberculosis and died.

“Political prisoners were then treated worse than real criminals,” he said.

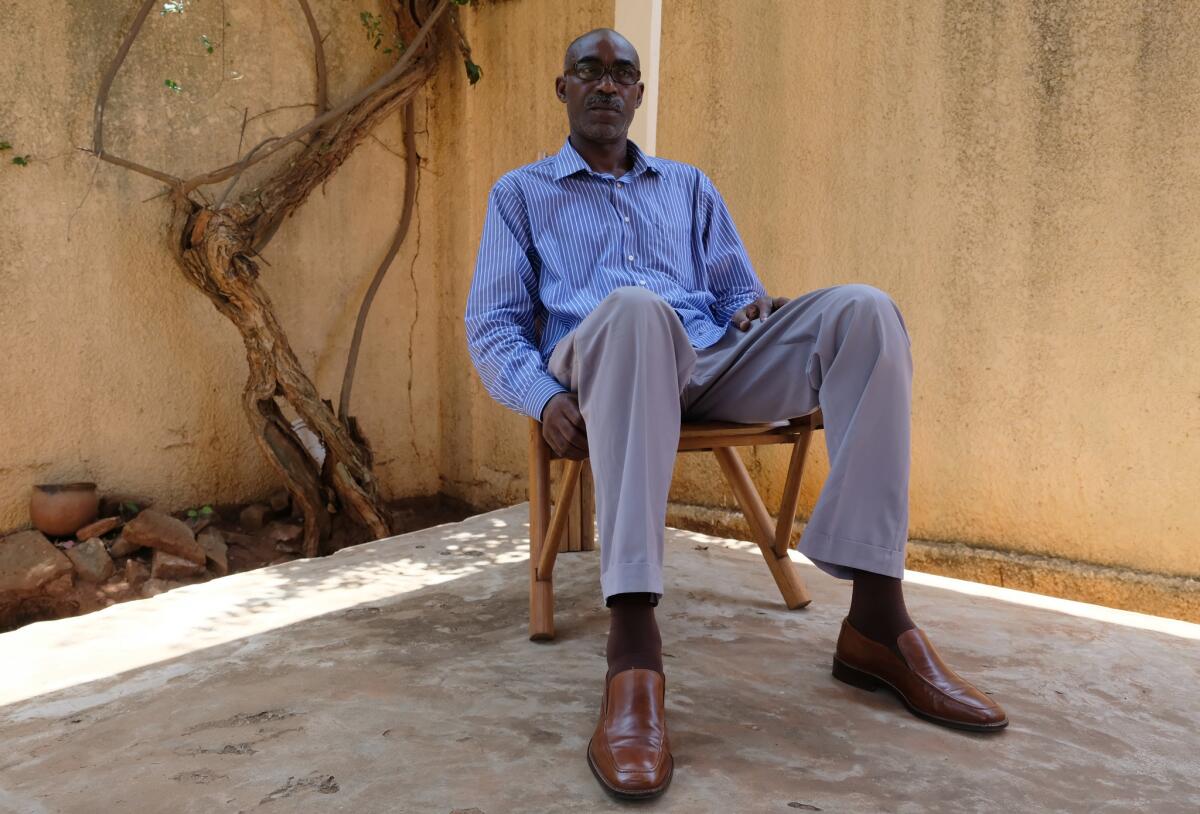

Now 33, Issa works in construction. Since his release in November, he has avoided all political activity because he worries that if he were arrested again, the government could go after his family.

“Today, if it’s me who gets hit, I feel the pain,” he said. “But if it’s my mom or wife who gets beaten, I will never forgive myself.”

Issa said he never even participated in the protest that landed him in prison. He briefly stepped away from work that day to photograph it. When soldiers grabbed him, they searched his phone and found images of the march, which were used as evidence against him.

“Everything is political. Even the trials are political,” he said. “Everyone pled not guilty, and everyone was found guilty.”

O’Grady is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.