Russian millennials look to their future: ‘If we don’t do anything now, we will keep living like our parents’

Russian millennials have really known only one leader: Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin.

They have no memories of the Soviet Union. They were in diapers when Boris Yeltsin was president.

On March 18, some will be voting for the first time. They will do so with the certain knowledge that President Putin, who has been either president or prime minister since 1999, will win again.

And yet, it could be a pivotal moment for this generation.

The next six years under Putin could be when millennials develop their political voice — whispers of which can be heard already in rap lyrics and in the demonstrations organized by opposition figure Alexei Navalny. Alternatively, Russia’s autocratic government could continue to tamp down youthful restlessness.

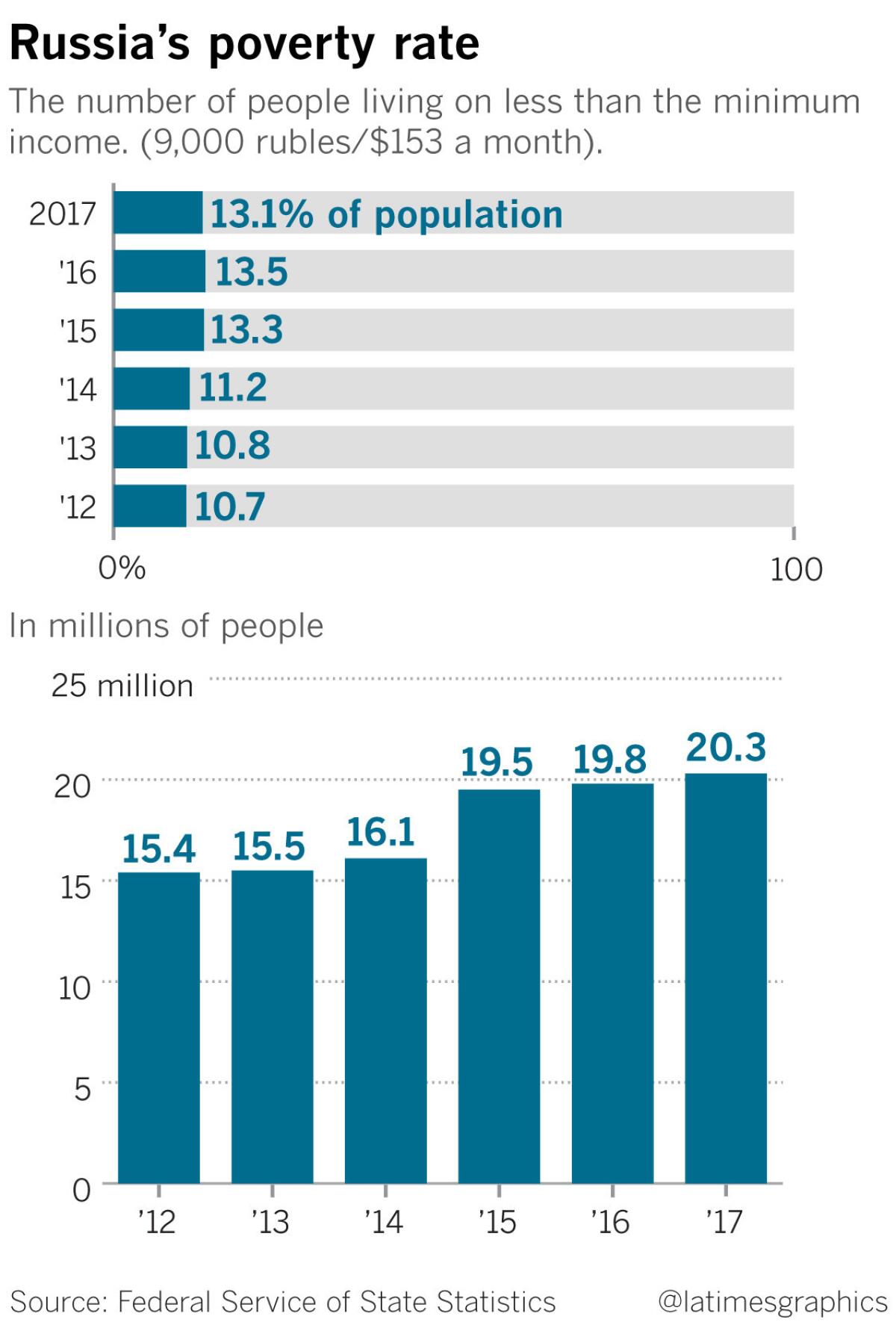

The millennial generation is inheriting a Russia in decline. Low global oil prices and Western sanctions aimed at punishing the Kremlin’s illegal annexation of Crimea have hurt the economy. Global oil consumption, which feeds Russia’s economy, is expected to continue its downward trajectory, and so is Russia’s birthrate.

Putin said recently that it was not his responsibility to “foster the opposition,” and he has made sure that Navalny is barred from running. The core of Navalny’s support has been the urban young, and he has managed to rally supporters in the street like no other candidate in post-Soviet Russia. Putin still commands overwhelming support among older generations.

Still, although thousands of young Navalny supporters risked arrest at anti-Kremlin demonstrations around the country during the last year, the ranks remain small, if growing. Recent polls indicate that 65% of people ages 18 to 23 would vote for Putin — if they go to the polls.

The Times interviewed young Russians across the country’s nine time zones to hear what was on their minds in the run-up to the election.

The rap star

Edik “Kingsta” Levin, St. Petersburg

Edik Levin came to St. Petersburg to be a student, but he stayed to become a rap star.

He arrived six years ago from the Siberian city of Tomsk, where he had decided at age 13 that he wanted to become a rapper, like Dr. Dre and other American stars. He called himself Kingsta.

His mother didn’t have much tolerance for his rap star dreams.

“She would always tell me, ‘Stop sitting writing; think about your future; you need to pay attention to school,’” Levin, 24, said.

Levin was convinced that if he wanted to be an artist or be in show business, he needed to be in St. Petersburg, the country’s second-largest city and, in many ways, its artistic capital. So he entered a university there to study international relations, but he wrote rap lyrics in his dorm room whenever he could.

“If I had told my mom that I was going here to write rap, she would have said I was an idiot,” he said.

Like most young Russian rappers, Levin was inspired by the lyrical sparring of Oxxxymiron, an Oxford University-educated Russian rapper known for his aggressive, curse-ridden verses. His lyrics frequently include offhand criticism of modern-day Russia and Kremlin policies.

The digital age has changed the way young Russians get their information. Millennials forgo the state media’s patriotic and anti-Western propaganda for YouTube channels and social media feeds. They exchange video bloggers’ and rappers’ links on VKontakte, the Russian version of Facebook.

A “battle” between Oxxxymiron, whose real name is Miron Fyodorov, and another rapper in August gained 3 million views overnight. It’s since been viewed almost 29 million times.

Rap battling, with its profanity-laden rhyming insults, started as an underground movement in Russia. It has now emerged as the millennial generation’s outlet for free speech.

“The older generation is used to being under control. They think if you have your small, family home, just be happy with that and don’t risk anything,” Levin said. “The youth is more progressive. School kids are going to [Navalny’s] rallies not because it is trendy, but because they have realized that if we don't do anything now we will keep living like our parents.”

After Oxxxymiron’s battle went viral, a lawmaker called for legislation to rein in media promoting rap, which he said represented “moral squalor.”

“We are a bit afraid now,” Levin said. “Before, we didn’t care when only 100,000 people watched our videos.” Now their battles get more views on YouTube than some TV stations have viewers, he said.

Levin’s YouTube channel contains a battle in which an insult to Putin is repeated several times in the back and forth between opponents. Levin considered bleeping it out, but then decided a few hours before posting it to keep it.

“I thought that what’s happening in the country is horrible. I am not planning to lead crowds and organize a revolution,” he said. “But if people such as the well-known rappers are afraid and keep silent, then nothing will change, then ordinary people will be silent as well.”

The frustrated

Arsen Avanesov, Volgograd

When Arsen Avanesov graduated from university last spring with a degree in psychology, he made a promise to himself: Stay in Volgograd, where he was born and raised, for a year and look for a job in his profession.

Avanesov wants to be a counseling psychologist, but in Volgograd, such a profession is looked down upon as some kind of scam, he said.

“In large regions like Moscow or St. Petersburg, the psychologists are trusted, they are visited,” he said. “But for Volgograd, I can say, people just don’t get it here.”

He’ll wait tables in the meantime, but if he can’t find a job within a year, he’s going to join the ranks of thousands of other young Russians from Volgograd and other provincial Russian cities and leave. His Plan B is to go to Moscow or St. Petersburg first and then try his luck in Western Europe, where several of his friends have found jobs in software design and programming.

Avanesov was 4 when Yeltsin resigned on New Year’s Eve 1999 and appointed then-Prime Minister Putin as acting president. Now 22, he has no memory of that transition of power and doesn’t see another one coming any time soon.

“I respect Putin as a person because when he took over Russia; times were hard and his methods have helped the country overcome the disorder,” Avanesov said. “But now the country definitely needs someone more modern, and I would say with different methods of governance.”

Avanesov doesn’t believe Navalny is the answer. “He can’t bring anything constructive,” he said.

“If someone were to ask me whom would I vote for today — although I won’t vote because I don’t want to — but I would vote for Putin,” he said. “I don’t see any other challengers who could do something better than Putin.”

History runs deep in Volgograd and its long embankments along the mighty Volga River, an important strategic and commercial artery in Russia. During the Soviet era, the city was a large industrial center with weapons, aluminum and shipbuilding factories.

But with the collapse of the Soviet infrastructure, many of Volgograd’s industries closed. Thousands of people were left without jobs. The city is now one of the poorest of Russia’s 15 cities with populations over 1 million.

This year the city, formerly known as Stalingrad, celebrated the 75th anniversary of the pivotal World War II battle fought here between the Soviet Red Army and Hitler’s troops. The city is still pockmarked with the scars of that battle, widely considered the greatest of the war and one of the largest in history. It lasted 200 days, cost nearly 2 million lives and nearly destroyed the city’s landscape before it ended on Feb. 2, 1943.

You can’t turn your head in Volgograd without seeing a war memorial. The tallest one, the Motherland Calls, is 279 feet from the base of the female figure to the tip of her sword thrust into air. She overlooks the city’s new $278-million stadium built for the 2018 soccer World Cup.

The global event will bring some temporary work for Volgograd’s young, especially those who can speak foreign languages and can feed the short-term tourist economy. But long-term opportunities for young people like Avanesov remain centered in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

“When I’ve been to Moscow, I realize that Moscow and Volgograd are two absolutely different towns of absolutely different countries,” he said. “No one is paying attention to us. We just grow up and we don’t know what to do here.”

The economic future: Russia’s petroleum engineers

Katerina Borodina, Tyumen

To get a sense of how important the oil and gas industry is to the city of Tyumen, and indeed the whole of Russia, consider a November ceremony honoring 17 young petroleum industry professionals after the completion of a vigorous training course at a subsidiary of Rosneft, Russia’s largest oil company. After swearing allegiance to the profession and promising “to achieve high results,” the trainees stepped across a stage to where a company executive dipped his finger into a hard hat full of sweet crude oil and swiped the forehead of each graduate.

With that, a new cohort of oil and gas professionals was indoctrinated into Russia’s most important industry.

It is an industry in which Katerina Borodina, 27, sees opportunities for young people to help develop Russia’s new oil and gas frontiers.

“What’s happening now on the offshore shelves can be compared with western Siberia 70 years ago, when we were starting to discover massive fields of oil and gas,” she said. “Now the shelf represents the same prospects.”

Borodina, raised in Tyumen by her mom after her dad died, surprised herself by becoming a geological engineer for Rosneft. She had good grades in school, loved to sing and wanted to become a doctor. But her chemistry scores earned her a full scholarship to the local university’s geological engineering department, and she fell in love with the subject within the first week of classes.

Tyumen is more than 1,000 miles east of Moscow in the heart of western Siberia. It was founded in the 16th century when the Russian Empire was pushing its expansion east of the Ural Mountains. Today, the city is developing rapidly around the oil and gas industry. Average salaries are higher here than in other parts of Russia. The city may lack the glamour of Moscow, but it has enough cafes, restaurants and shopping malls to cater to its newly prosperous population.

Borodina isn’t much on the bar and club scene. She works a lot, even on the weekends. She spends a lot of time with her mother, Tanya, whom she likes to take out for a night of karaoke.

She worries about her mother, who has struggled to raise her and her half brother, who’s 14. She especially worried about her grandmother, whose pension is about $200 a month. Borodina said her salary is slightly higher than the $700 average monthly salary for young professionals in Tyumen, so she can afford to help out her family.

“I think Russia offers a lot of opportunities for young people, but it’s completely forgotten about its older people, the people who worked all their lives for the state,” she said. “It’s not right how hard it is for them to get by now.”

Borodina says she hasn’t given much thought to voting this time around. She said she probably will vote, but she doesn’t know for whom. It doesn’t really make much difference whether she votes or not, she said.

“We know who’s going to win, don’t we?” she said.

Anastasia Reunova, Tyumen

Anastasia Reunova, 27, is one of the few women who works in the data analysis department of a major oil services company in western Siberia. When she was in college, professors would tell her to pick another profession because going into this business as a woman would be too hard.

She proved them wrong, was hired by Salym Petroleum Development, a joint venture between Royal Dutch Shell and Russia’s Gazprom Neft, and her career soared. She’s done stints in the company’s field offices in Salym, a remote oil field deep in the Siberian wilderness. It’s a 14-hour trip to get there from Tyumen. Once there, the workers stay in dorm-like accommodations with modern amenities such as gyms. Though the fieldwork could feel isolating after six weeks, the camaraderie made it worth it, she said.

So did the pay. Fieldworkers make 1½ times the monthly salary of a typical home office worker in Tyumen. After two years of working monthlong field shifts, Reunova was able to save enough money to buy a car and make a down payment on a one-bedroom apartment.

“It’s not bad, right?” she said as she walked around the unfinished, bare walls of the new apartment she will share with her 18-month-old son and her boyfriend.

Reunova’s life is something that her mother could have never imagined. Her generation didn’t grow up with the benefits of the Soviet system, in which apartments and jobs were assigned by the state.

“We’ve had to be more creative and figure things out on our own because the state doesn’t do that anymore,” she said. “I think our generation is more self-sufficient. We’re figuring things out on our own because we’ve had to.”

The anti-corruption protests that rattled local authorities across the country this spring and summer didn’t get much traction here.

“Russia will always be Russia with or without corruption,” she said. “Everyone knows it exists.… But we can’t change things, so we just accept that it exists and work around it. Our generation has figured out how to do that.”

Reunova doesn’t know whether she will go to the polls on March 18, although she might be enticed by the promotional giveaways that authorities use to lure people to vote. “They give you all these incentives to go, you know, like cakes and prizes, so … maybe I will just go to see what is there,” she said.

The Navalny activist

Nikita Panfilov, Vladivostok

The volunteers in Navalny’s campaign office in Vladivostok tell stories of police harassment like soldiers rehashing battle scenes. Of the dozen young volunteers sitting around the conference table, at least half have been dragged into police vans and held for hours for participating in unsanctioned protests. One has served three stints of 20-day jail sentences. Another had police from the anti-extremist unit search his apartments without a warrant.

Nikita Panfilov, 20, eluded arrest for months as a volunteer, but the hours he has spent waiting outside police stations for his friends to be released have changed the way he views his country. He has become a devoted member of Navalny’s campaign, whose nationwide appeal to Russian youths has shaken the Kremlin.

Then on Jan. 23, 10 months after Panfilov started volunteering for the Navalny campaign, police came to the campaign office and escorted him to a police station for questioning. They threatened to charge him with trying to organize an unsanctioned rally but released him after several hours with no charges.

“Interesting part is that I don’t even feel nervous,” he wrote on Telegram, a messaging app, shortly after being released. “Just a bit disappointed. Horrible things are happening.”

The police are now harassing his parents and grandparents, and that has him worried, he said.

Navalny has little chance of becoming president; the Kremlin won’t even give him permission to register his campaign. But his anti-corruption campaign has gathered more than 100,000 volunteers across the country, most of them young, and is teaching members of an otherwise apolitical generation how to organize politically.

“For young people in Russia, Navalny’s campaign is first of all an opportunity and also something very new,” Panfilov said. “We hadn't seen anything like this before. All our childhood, all our youth, we had that strong understanding that nothing will change.”

Panfilov was born and raised in Vladivostok, Russia’s most important port in the Far East. People in Vladivostok frequently compare their city to San Francisco because it’s tucked into a scenic bay and spread out among rolling hills.

The city also has a bit of an iconoclastic spirit; it was one of the last cities in the Russian Empire to support the Bolsheviks.

Located about 4,000 miles east of Moscow, the region surrounding Vladivostok shares a border with China and North Korea. Ships come in from the Sea of Japan, also known as the East Sea, to transport goods west on Russia’s Trans-Siberian Railway.

Panfilov understands why his parents see Putin as their savior, having struggled through the crime, banditry and chaos of those turbulent, post-Soviet years. But the cost of Putin’s economic stability is now bumping up against young Russians’ desire for a different future.

When he looks around, Panfilov said he sees the scars of the breakup of the Soviet Union. Factories aren’t working, young people leave to work in China or Korea. Some make it to Europe. Russia’s best computer programmers work outside the country, he said.

The world sees Russia as one big gas station, he said.

Panfilov studies Korean at one of Vladivostok’s universities. When he’s not studying, he’s often hunched over a notebook, drawing detailed, pen-and-ink sketches in the one-room apartment he shares with his girlfriend.

Most of his free time is spent at the Navalny headquarters helping campaign for signatures to allow Navalny to register his candidacy. Many of his Saturday mornings are devoted to handing out leaflets on commuter trains.

What bothers him most is that many are willing to complain but not look for solutions.

“Either people will live worse and keep believing the propaganda ... or people’s anger will get so bad that any peaceful change of power will become impossible,” he said.

Ayres is a special correspondent.

This story was supported with a grant from the United Nations Foundation

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.