Why a ban on Huawei is being ignored by some of the oldest U.S. allies in Asia

Reporting from Manila — On the site of a former World War II garrison where the U.S. Army trained local troops — and later firebombed tunnels to drive out occupying Japanese soldiers — the Philippines has built a shining symbol of its modern ambitions, a master-planned commercial district billed as one of the safest in the country.

Watching over Bonifacio Global City — a square-mile oasis of glinting high-rises and tree-lined streets southeast of Manila — are more than 200 high-definition security cameras. They were furnished by a company that has become a target in a new U.S. war: the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei.

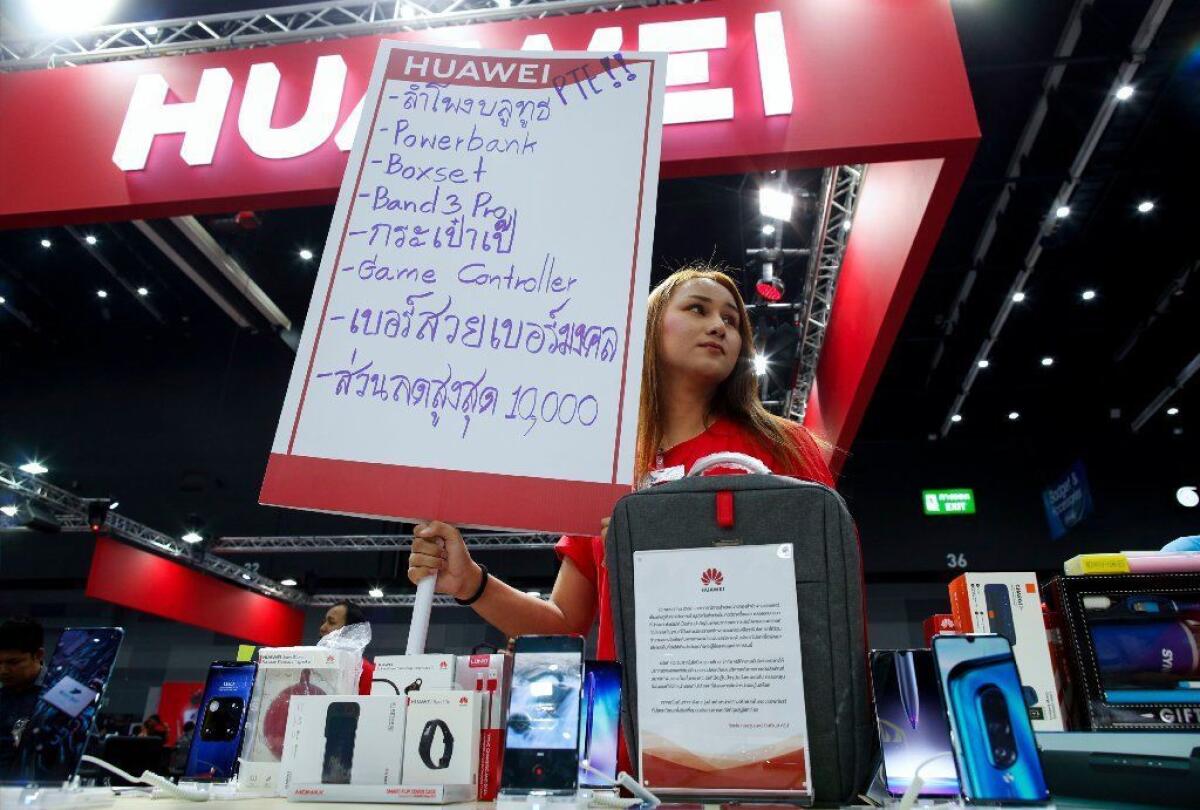

The surveillance network is one example of Huawei’s extensive inroads in Southeast Asia, where it has supplied much of the digital infrastructure and devices that have helped drive a decade of economic expansion: laying undersea cables, building mobile networks, establishing research labs, wiring government offices and commercial hubs, and selling more smartphones than almost any competitor.

Now the United States, locked in a trade war with China, is urging countries to cease doing business with Huawei, citing security risks posed by its alleged ties to the Chinese government.

Who is the man behind Huawei, and why is the U.S. intelligence community so afraid of his company? »

But the Philippines — one of the oldest U.S. allies in Asia — has not signed on to the U.S. ban and is moving ahead with plans to use Huawei equipment in upcoming trials of ultrafast 5G wireless systems and a multi-city surveillance program far more advanced than that of Bonifacio Global City.

The Philippines’ approach illustrates how the U.S. effort to cripple Huawei “has really fallen flat in Southeast Asia,” said Brian Harding, a fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

It also suggests a further erosion of U.S. influence in a region where its longtime security partners are increasingly swayed by Chinese investment.

“There’s a skepticism of whether the U.S. arguments about the nefarious nature of Huawei and its connections to the Chinese government are actually valid,” Harding said. “And there’s a frustration the U.S. government isn’t bringing a viable alternative to the table.”

With 650 million people — roughly half of them younger than 30 — and an economy whose output has nearly doubled in the last decade, Southeast Asia has emerged as an important market for tech companies. It is particularly crucial for Huawei because mature markets such as Japan, Australia and parts of Europe have already heeded Washington’s call to limit dealings with Chinese tech suppliers.

So far, no country in the region has banned Huawei devices. All but one are still planning to use the company’s technology for 5G, the next-generation wireless network seen as crucial to driverless cars, digital medical services, smart cities and other innovations.

Analysts say such countries are reluctant to exclude Huawei — whose products are considered equal to or better than those of Western rivals such as Nokia and Ericsson, and often 20% to 30% cheaper — if it means falling behind in the 5G race.

“Huawei has established its reputation for value-for-money networking equipment and that is highly attractive to developing and growth markets,” said John Ure, director of the Telecommunications Research Project at the University of Hong Kong.

Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad said last month that his country would use Huawei technology “as much as possible.” He dismissed concerns that it could be used for espionage by half-joking: “What is there to spy in Malaysia?”

Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong told an audience at the Shangri-La Dialogue, an annual regional security conference, that while the island city-state had yet to decide which 5G providers to use, “it’s quite unrealistic to expect 100% security from any telecommunications system you buy.”

Telecom companies in Cambodia, Indonesia and Thailand — another long-standing U.S. military ally — have also signed agreements with Huawei and rivals to develop 5G networks. Japan is alone among Asian countries in barring Huawei from 5G contracts.

At the Shangri-La gathering this month, U.S. officials warned defense leaders that they would stop sharing information with countries that used Huawei for 5G.

Andrea L. Thompson, the top State Department official for international security affairs, said that persuading countries to boycott the Chinese company, “like any diplomatic effort, takes time.”

“If you want to expose your network to be a dirty network,” Thompson said, “there’s a price to pay with that.”

The debate over Huawei is particularly fraught in the Philippines. A former U.S. colony that has a seven-decade treaty alliance with the United States, the country of 105 million people has moved closer to China under President Rodrigo Duterte, who has downplayed maritime disputes with Beijing in order to secure greater economic cooperation.

Huawei’s involvement in the Philippines began in 2010, under a previous government, with a $700-million deal to modernize domestic telecom giant Globe’s network. Globe officials have said they believe security concerns about Huawei are overblown and are continuing plans to roll out 5G service using Huawei equipment this year.

“Huawei remains an important partner,” said Globe spokeswoman Maria Yolanda Crisanto.

Some in the Philippine military establishment “share U.S. concerns about Huawei, but for now they are giving the administration the benefit of the doubt,” said one senior security official, who requested anonymity to avoid being seen as criticizing the president.

Still, the decision over Huawei represents a challenge to Duterte’s bid to balance his relationships with China and the United States.

“Duterte is trying to maintain the political status quo,” said Jake Saunders, a Singapore-based analyst for ABI Research. “America’s economic and political connections go back multiple decades, but China has got a lot of money. That duality is putting a lot of friction on” the decision over Huawei, he said.

Huawei is also playing a major role in the Philippine strongman’s anti-crime push.

One sign of the shift away from the U.S. is Bonifacio, a privately run district built on the site of Ft. McKinley, an Army base established after the Spanish-American War ended in 1898. After flushing out Japanese troops during the bloody Battle of Manila, which helped bring an end to World War II, the U.S. handed the base to local control in 1949. The land was eventually razed for a business hub to relieve congestion in Manila.

In a second-story office across the street from the Philippine headquarters of Unilever, security officers watch a wall of television screens showing images beamed wirelessly from closed-circuit Huawei cameras.

If there’s a road accident, traffic wardens are alerted to reroute vehicles. Crime is virtually nonexistent.

Huawei’s corporate website touts the development as “a model of pristine city planning.” Developers hope 5G networking will allow for further advances such as facial and vehicle recognition.

“The dream is to become a truly smart city, but 5G is one of the bottlenecks,” said Sean Luarca, a spokeswoman for the development authority. What’s happening to Huawei, she added, “is unfortunate, because their products have served their function well. We trust them until proven otherwise.”

Duterte’s government has also announced a $397-million deal with a Chinese state-run company for a project called Safe Philippines, which will install more than 10,000 high-definition security cameras across Manila and in the city of Davao, the president’s hometown. Federal officials say the surveillance system will help reduce crime and improve police response times.

Analysts expect that some equipment will be supplied by Huawei. Officials in charge of the project said sensitive data would not be stored and the system would include “the necessary firewalls to protect the system from hackers and other threats.”

In an interview, Diosdado T. Valeroso, a senior official in the Department of the Interior and Local Government, said authorities were “very confident” about being able to protect data no matter which company supplied the technology.

Huawei “is big, it has a big market share, and anyone can go to them and buy the equipment they need,” Valeroso said. “We welcome the contractor using any brand they want, as long as it conforms with our specifications.”

The major outlier in the region is Vietnam, which is shunning Huawei in favor of developing its own 5G technology, probably in partnership with Nokia and Ericsson. Vietnam is deeply suspicious of China after long periods of war throughout their histories and shares Washington’s concerns that Huawei could serve as a tool for Chinese intelligence.

“Security is one of the foremost considerations not to rely on Huawei,” said Le Hong Hiep, an expert on Vietnam at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore. “Secondly, Vietnam desires to be self-reliant in the long term in technology and that’s particularly true of 5G.”

Huawei’s rivals haven’t given up on the region. Nokia of Finland has signed agreements to run 5G trials in Thailand and Malaysia, as well as in the Philippines, where it reached a deal with the country’s biggest telecom operator, PLDT.

Other companies were delaying 5G decisions, especially after President Trump suggested he might lift sanctions against Huawei as part of a potential trade deal with China. That remark appeared to undercut U.S. arguments that the company couldn’t be trusted.

“The obvious conclusion is to take the security issue with a pinch of salt,” said Ure, of the University of Hong Kong, who added that most countries’ economic ties with China could prove more potent than fading U.S. leverage.

“China is the elephant in the room,” Ure said, “while the U.S. sends out too many mixed signals.”

Bengali reported from Manila and Pierson from Singapore.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.