A brazen job scam exposes an employment crisis in India

Reporting from New Delhi — The two young engineering graduates had just been told by a job recruiter that they’d aced their interviews, but on the overnight train back to their hometown in southern India, they began to wonder if it was too good to be true.

After struggling to find decent work, the 26-year-olds seemed close to landing good jobs with the state-owned Oil and Natural Gas Corp., one of India’s biggest companies. Pulling out a cellphone in the clattering train car, they tapped out a web search for “ONGC” and “fake jobs.”

They had heard about graduates conned into paying recruiters for jobs that didn’t exist. And the recruiter who summoned them was asking for thousands of dollars.

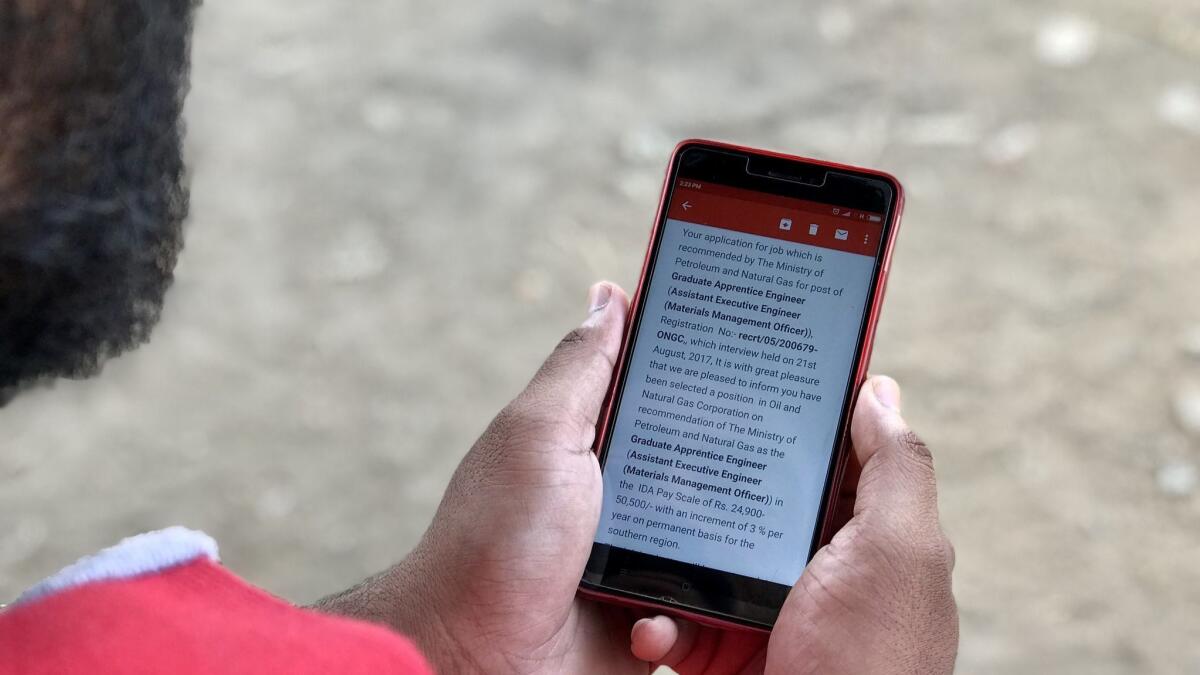

But their search turned up nothing nefarious, so they relaxed — and emptied their parents’ bank accounts before reporting to work in March, offer letters in hand.

Their initial suspicions proved well-founded: The letters were fake. The pair had been taken in by a job scam, the kind that has swept India as con men capitalize on the anxieties of a young generation struggling in the shadows of the world’s fastest growing major economy.

India’s shiny growth statistics mask a gloomy paradox: Surveys show unemployment is rising, wages remain low and the most educated are the least likely to find work.

More than four years after Prime Minister Narendra Modi swept into office pledging to meet the demands of the millions of fresh graduates entering the labor market every year, his efforts to boost manufacturing and the digital economy have failed to generate significant numbers of new jobs. And the share of Indians who are gainfully employed appears to be shrinking.

About 426 million Indians were employed or looking for work this year, down from nearly 440 million in 2016-17, surveys show. In 2015, the most recent year for which data were available, more than 16% of Indians with graduate degrees were jobless, three times the national average, according to a report by the Center for Sustainable Employment at Azim Premji University in Bangalore.

The only bright spot is a vast government sector, which pays better and affords more stability than nearly any private industry — resulting in intense competition for posts. This year, when state police in northern India posted an opening for a peon — a lowly messenger job requiring a fifth-grade education and paying less than $300 a month — more than 93,000 people reportedly applied, including 3,700 PhD holders.

Many public sector applicants turn to recruitment agencies, an unregulated market rife with cheaters.

“We have a very deep and large unmet demand for work, and for jobs of a particular kind, and criminals are preying on that,” said Amit Basole, an associate professor of economics at Azim Premji University.

A recent story in the Economic Times described job rackets as “a booming industry” and described how scammers created fraudulent websites, disguised their email addresses and infiltrated company offices to trick job seekers.

The New Delhi hoax was particularly audacious because the crooks lured graduates to interviews inside the secured offices of a government ministry in the heart of the capital. Conspiring with low-level ministry staff, they created fake offer letters using the oil company’s logo, email addresses and digitized copies of official signatures.

Investigators believe at least 20 job seekers were duped, forking over hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“This scam was not just daring but also intelligently executed,” Delhi deputy police commissioner Bhisham Singh said.

We have a very deep and large unmet demand for work...and criminals are preying on that.

— Amit Basole, economics professor

Victims say their lives have been ruined.

“My family doesn’t want to speak to me,” said Sampat, who lost more than 1.2 million rupees, or about $17,000, including all the money his parents had saved for his sister’s wedding.

His friend and former classmate Jivan — both men, fearing retribution from the scammers for reporting them to police, spoke on condition that their full names not be published — liquidated his own family’s long-term savings account, about $8,000. They had received the money in 2010 as a settlement when Jivan’s father died in a workplace accident at a rice factory.

Jivan, while an undergraduate, had worked evenings at the factory to support his mother and two siblings, earning about $5 per day. In 2016, he earned a master’s degree in civil engineering from a private college a few miles from his house in Telangana state. The school is among many of questionable quality that have sprung up across India to meet the growing demand for higher education.

Jivan was unemployed when a recruiter who identified himself as Ravi Chandra phoned in April 2017. Together, he and Sampat went to visit Chandra in an office inside a glass building above a BMW dealership in the city of Hyderabad.

As about a dozen other young applicants milled about, Chandra — trim, well dressed, pleasantly chatty — showed copies of offers he said he’d gotten for recent graduates.

“It looked good,” recalled Jivan, his square jaw twitching. “He had other clients, and he said there were lots of government jobs.”

Chandra eventually introduced them to another man, identified as Randhir Singh, who said he was recruiting for the oil company. Singh and Chandra said their fees would total $20,000 each — more than double what the jobs would pay in a year.

Still, the young men believed they were being offered tickets to stability for their families. Jivan’s mother could quit the janitorial work she had taken on after his father died; Sampat, the eldest of three, figured he could finance his brother’s studies.

After each had paid about half what the recruiters were asking, they were invited to New Delhi for further interviews. The emails came from an oil company address and told them to report to Krishi Bhavan, a sprawling government office complex near the Indian Parliament.

Last August, after a 26-hour train journey, Sampat and Jivan met a clerk outside Krishi Bhavan who led them through security and into the building. Another took them to a ground-floor office where five people were seated around a table.

A metal plate reading “ONGC” hung from the wall, but Sampat recalled being confused — signs outside the door said the office belonged to the Ministry of Rural Development.

The interviewers said a certain number of jobs at the oil company were set aside for the ministry, which would be making the selections.

Investigators would later learn that the scammers had used “spoofing” technology that made it seem like their calls and emails were coming from ONGC offices. The ministry clerks were in on the con too, tasked with finding offices whose occupants were away.

“In such a large building, nobody noticed what was happening,” said Singh, the police official.

After they got back home, Jivan brought his mother to meet Randhir Singh. By this point he had spent the entire payment from his father’s death and they’d had to borrow more from relatives.

Five months would pass before they were called back to New Delhi in early February. The same clerk met them at the entrance but led them on a circuitous path to a different meeting room.

Only later would Sampat reason that the clerk was probably trying to avoid CCTV cameras.

The interviewers presented them with photocopies of offer letters, printed on bond paper with the oil company logo. They traveled to a famed Hindu temple at Rishikesh, north of New Delhi, to receive blessings, and the following month they took an eight-hour bus trip to the coastal city of Kakinada to report for work.

Recalling the moment an ONGC human resources officer told them their letters were fake, Jivan’s voice grew quiet. Tears welled in his eyes. He wondered why he’d fallen for the scam.

“People started questioning me when I got home, saying, ‘Why did you have to give them so much money?’” he said. “I thought, this is India. This is what you have to do.”

He locked himself in the family’s one-room apartment for a week. His mother was hospitalized for stress.

Even seven months later, he sometimes hears her lying awake at night, crying.

Read more: Why millions of Indian workers staged one of the biggest labor strikes in history »

In September, acting on the pair’s information, Delhi police arrested seven suspects, including the clerks and the man who called himself Randhir Singh, a name that turned out to be fake. Chandra and another suspect, who took part in the interviews, remain at large.

To fight scams, some companies have begun posting samples of fake letters on their websites, stamping their correspondence with digital QR codes and reminding applicants that they don’t demand money from potential hires.

Investigators have yet to trace the money Jivan, Sampat and other victims lost. Sampat’s parents were so angry that he moved out and has yet to return, even after he found a job.

Jivan, too, recently found work through a relative, a construction job that pays one-quarter of what he thought he’d make at the oil company.

“Catching the criminals makes no difference,” he said, “unless we get our money back.”

Masih is a special correspondent.

Shashank Bengali is South Asia correspondent for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @SBengali

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.