U.S. foreign aid: A waste of money or a boost to world stability? Here are the facts

It has long been a divisive issue: how much money the United States gives to foreign nations in aid, what kind of effect development assistance actually has on recipient nations, and whether America should be involved in the aid-giving business at all.

Advocates of foreign aid say programs backed by U.S. funding help feed the needy, promote social and economic progress, and foster political stability. Critics, on the other hand, point to fraud and the misuse of aid, inadequate tracking of provisions, and the prospect of nations becoming dependent on U.S. handouts.

So what’s true and what’s false about one of politics’ most contentious issues?

More than 20% of America’s federal budget goes to foreign aid.

False

The amount is actually about 1%. The current projected spending for fiscal year 2017 is $4 trillion. The Obama administration had planned for $41.9 billion in foreign aid for this year. Polls show that Americans typically believe that the U.S. spends 25% to 27% on foreign aid.

Afghanistan is slated to be the biggest recipient of U.S. foreign aid this year.

True

The planned amount of American aid for Afghanistan in 2017 is $4.7 billion, according to the website ForeignAssistance.gov, a tool for tracking U.S. foreign assistance spending. Funding to this Asian nation is intended to support the agricultural sector by creating jobs; build a national education system; assist reproductive health; and establish basic infrastructure, such as schools and hospitals, according to information published by the U.S. Agency for International Development, or USAID. In 2014, Afghanistan received $7.3 billion in foreign assistance from the U.S., of which more than half went toward conflict prevention and security, according to USAID.

Israel comes in second among U.S. aid recipients, with a planned disbursement of $3.1 billion in 2017, according to U.S. government statistics. Jordan is third at $1 billion.

Slashing foreign aid would reduce the federal deficit by as much as 20%.

False

Experts say cutting the foreign aid budget, which currently amounts to $50.1 billion, would do very little to reduce the deficit, which in 2016 was $552 billion.

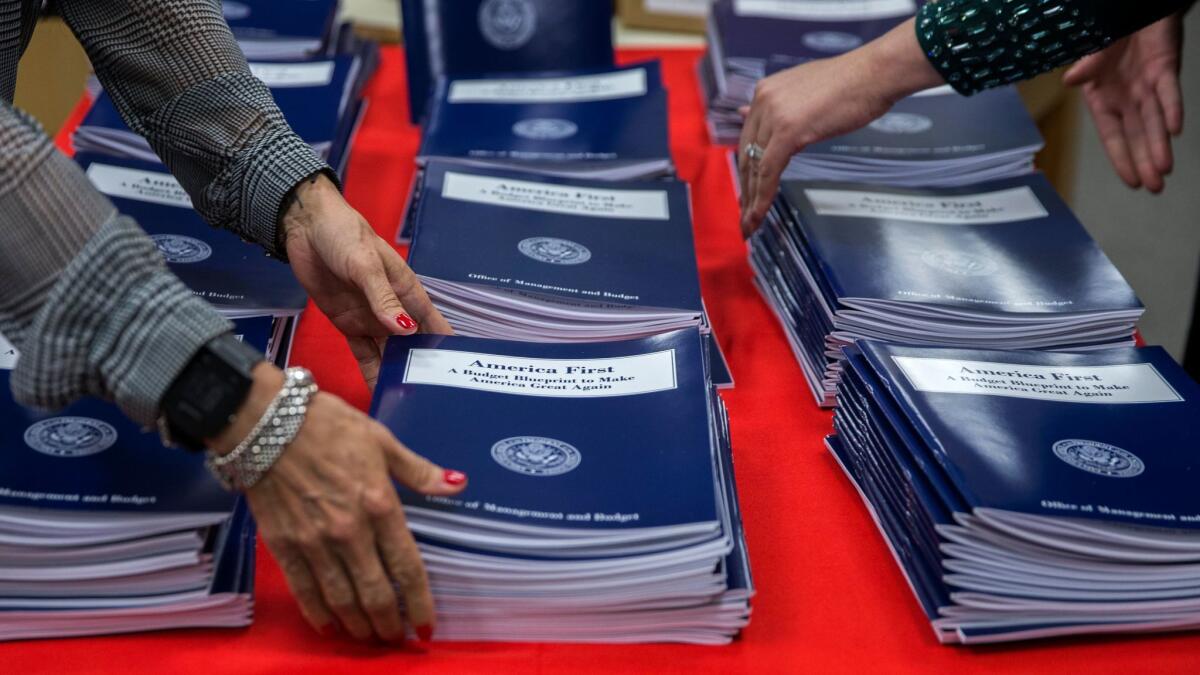

President Trump wants to slash the U.S. foreign assistance programs by more than 20%.

True

In March, as part of his suggested budget for fiscal year 2018, President Trump proposed a combined budget of $25.6 billion for both the State Department and that U.S. Agency for International Development. That would be an estimated 28% cut in current spending on foreign assistance programs and U.S. diplomatic engagement, which total $50 billion for the current fiscal year.

According to a 15-page State Department budget document obtained by Foreign Policy magazine and detailed in a report by the publication in April, global health programs would take a 25% cut in aid while, among other sectors, the Bureau for Food Security, which works on eliminating hunger, would lose 68% of its funding.

Aid to Israel will face the ax next year.

False

Aid to Israel is safe — at least under Trump’s proposed budget. Last year, the U.S. signed a 10-year defense deal with Israel that promises to provide the Middle Eastern nation a record $38 billion in security aid.

Scandals that have beset U.S. aid programs include theft of malaria drugs and laundering of HIV/AIDS program funds.

True

Millions of dollars worth of antimalarial drugs provided by the U.S. government are being stolen and resold on the black market in Africa, according USAID’s office of inspector general, which monitors the agency. The U.S. government fights malaria in 19 African countries through a program called the President’s Malaria Initiative.

In January, the inspector general’s office reported that an investigation it launched in the West African nation of Guinea led to the arrest of eight people on suspicion of illegally selling USAID-issued antimalarial drugs in public markets of Conakry, the country’s capital. U.S. funding for combating malaria has exceeded $72 million since fiscal year 2011 and amounted to $15 million in fiscal year 2016, according to the office.

Last year, the monitoring agency announced the relaunch of its Make a Difference Malaria hotline to make it easier for Nigerians to report stolen, counterfeit or resale antimalarial drugs. The hotline offers rewards of $100 to $10,000. A similar program is underway in Malawi, according to the office.

USAID’s funds have also fallen victim to money laundering. In February, the agency announced the arrest of a South African doctor, Eugene Sickle, who served as deputy executive director of the Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute program. Sickle is being investigated for his alleged role in a fraud scheme that targeted funds from USAID, which since 2012 has awarded grants worth nearly $77 million to help strengthen treatment programs for HIV/AIDS patients, according to the agency.

Once a foreign aid recipient, always a foreign aid recipient.

True and false

Critics have contended that foreign aid make nations perpetually needy and unable to break the cycle of dependency.

“Perhaps the largest reason is corruption,” James M. Roberts, a research fellow for economic freedom and growth at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank that has called for a scaling back of USAID funding, wrote in a 2014 commentary. “It’s the ‘pre-existing condition’ that keeps many aid recipients from ever recovering. It’s a major obstacle to economic growth.”

Some critics single out Afghanistan, where international aid has become the backbone of its economy, as a likely candidate for dependency on aid. They point to a 2014 report from the the office of special inspector general for Afghanistan reconstruction, which said “evidence strongly suggests that Afghanistan lacks the capacity — financial, technical, managerial or otherwise — to maintain, support and execute much of what has been built or established during more than a decade of international assistance."

But several of America’s key trading partners were once recipients of U.S. aid and today receive limited, if any, assistance from USAID, according to data from the agency. South Korea, for example, has been dubbed by some analysts as “a poster child for successful poverty eradication” and is today itself a donor of humanitarian assistance. USAID calls the Asian nation “a textbook example of aid-recipient-turned donor.”

According to a 2012 report from the Center for Global Development and the Center for American Progress, “nations need not be aid recipients forever.”

“In the 1960s, nations across Latin America and Asia were dismissed as perennial basket cases yet countries in both regions combined sensible reforms with a jump-start from U.S. assistance programs to achieve dynamic, lasting growth,” according to the report.

Foreign aid has long enjoyed bipartisan support among Republicans and Democrats.

True

In the 1990s, foreign aid bills had a hard time passing through Congress, but that changed with Presidents George W. Bush and Obama, said George Ingram, a senior fellow in the global economy and development program at the

Speaking during a “Brookings Cafeteria Podcast” last month, Ingram said the last Congress had passed eight bills supporting foreign aid. After Trump proposed cuts to foreign aid and international diplomacy in his budget, 43 U.S. senators signed a bipartisan letter urging against the reductions.

Foreign aid does more harm than good and is a waste of money.

Depends on whom you ask

Supporters’ arguments include:

— Helping to end maternal and child mortality. At least 4.6 million children and 200,000 mothers are alive today in part because of USAID-funded programs, agency officials said.

— Ensuring that people don’t go hungry. The U.S. government’s Feed the Future initiative has helped more than 9 million farmers gain access to new tools or technologies such as high-yielding seeds, fertilizer application, soil conservation and water management, according to USAID.

— Improving reading instruction and creating safe learning environments for more than 41.6 million children from 2011 to 2015.

— Providing access to clean water and sanitation. As of 2015, more than 7.6 million people had received improved access to drinking water and more than 4.3 million people had improved sanitation.

— Helping to stabilize nations by promoting democracy, human rights and good governance around the world.

Detractors counter that:

— U.S. aid shouldn’t go to countries that harbor terrorists who want to harm Americans, such as Pakistan, where Osama bin Laden had taken refuge not far from a Pakistani military compound before U.S. intelligence discovered him there. The U.S. has drastically cut aid to Pakistan in recent years, but the South Asian nation still received $383 million in 2016, according to U.S. government data, and $742,200,000 is planned for Pakistan in fiscal year 2017.

— There is too little accountability for those who abuse U.S. aid through theft or misuse.

— Foreign aid encourages corruption and conflict and stifles the will to pursue free enterprise, because recipients become dependent.

— A saturation of food aid can undermine opportunities for local agricultural markets to develop.

— American money should be spent on aiding Americans, such as the almost 50,000 U.S. veterans who are homeless, according to data from the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

For more on global development news, see our Global Development Watch page, and follow me @AMSimmons1 on Twitter

UPDATES:

5:05 p.m., May 10: This article has been updated to reflect current data from the U.S. Agency for International Development and the website ForeignAssistance.gov.

This article was originally published at 6:45 p.m. on May 3, 2017.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.