In Karachi, Pakistan, few families are untouched by crime

Karachi is Pakistan’s economic hub and also its crime capital. If you haven’t been kidnapped, you’ve probably been mugged.

W

hen the gunmen slid in the back seat behind Saad Qaimkhani and his friend, the college student thought they were after his cellphone, or maybe the car. Then the men told them to drive.

Almost all private cars in this shoot-'em-up city have an embedded device that allows a security company to lock the engine of a stolen vehicle remotely. In this case, though, when a bystander alerted the security company and the car came to a standstill, the thugs ordered the young men into another car and drove them around Karachi to make sure they weren't being tailed.

That's when Qaimkhani knew for sure: He was being kidnapped.

He and his friend were taken to a two-room house near the Northern Bypass, a neighborhood filled with poorly built one- and two-story structures where police are as rare as snow.

Their phones and wallets were taken and their legs chained to a bed. They were interrogated about family wealth and contact numbers, then beaten so their relatives would hear their panic during ransom calls afterward. The three kidnappers demanded $300,000 for the pair.

For six weeks, Qaimkhani and his childhood friend were locked to the bed, sleeping chained together on the mattress, interrupted only by visits to a primitive toilet. The two chain-smokers squabbled over their one-pack daily allowance and ate cheap, bad-tasting food. Occasionally, they were allowed to watch Bollywood DVDs.

Karachi is Pakistan's largest city, its economic engine and financial hub. The bustling port juggles thousands of shipping containers a day, and its nine-story steel-and-glass stock exchange — whose index is up more than 40% this year, one of the world's best performers — hosts traders doing million-dollar deals.

It's also the nation's crime capital, a place where even middle-class people have personal guards and gunfights erupt among rival gangs muscling into one another's territory. Foreign Policy magazine recently ranked Karachi the world's most dangerous mega-city, topping Bogota, Colombia; Lagos, Nigeria; and Mexico City.

A string of Pakistani leaders, including Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, have pledged to clean up Karachi, where teeming millions elbow for an edge in the tropical heat. Owners don't leave their property empty, even for a few days, because they worry that gangs will take it over. Even in posher areas, residents venture out at night on unlighted streets at their own peril.

Little reform is expected, given the clout of local political bosses and their affiliated criminal gangs. Of the estimated 10,000 police officers on duty at a given time, more than half are reportedly chauffeuring VIPs around. According to a leaked 2009 U.S. Embassy cable, the armed militia of one political party alone numbered 25,000.

In March, police official Niaz Khoso reported that half the sprawling city was a no-go area for police, who routinely advise the relatives of kidnapping victims to take the lead in dealing with the criminals.

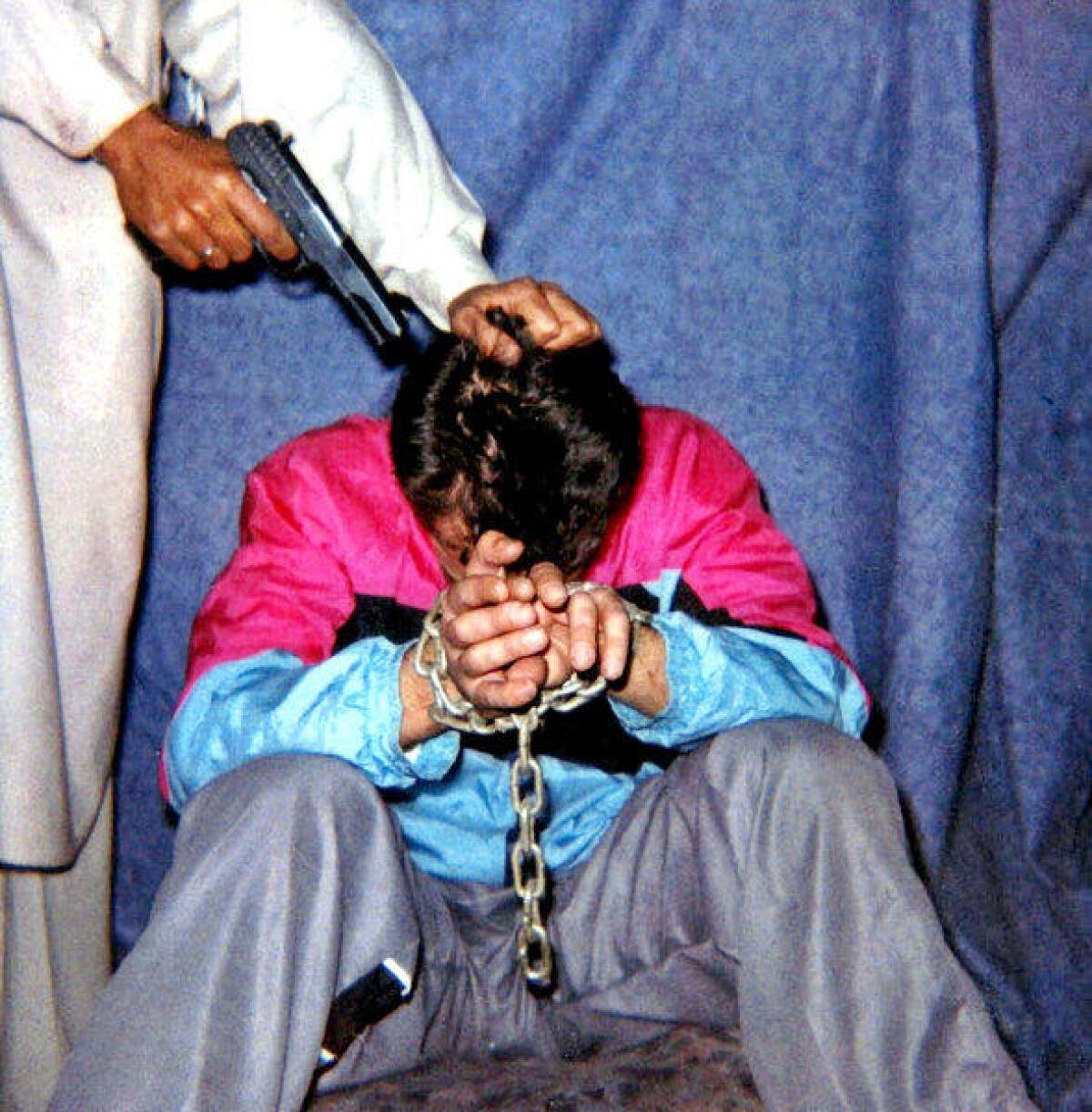

Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl is seen in this picture sent to news media organizations by his kidnappers. Pearl was abducted in Karachi, Pakistan, in January 2002 and later killed. (CNN / Getty Images) More photos

In the city where American journalist Daniel Pearl was abducted and beheaded in 2002, few families remain untouched.

On a recent afternoon at Karachi's upscale Atrium mall, where patrons are told to keep their guards outside, most customers interviewed said they had friends or family who had been kidnapped, and all had themselves been mugged. Middle- and lower-middle-class residents described a beleaguered existence, one in which they mostly stay home, hide their cellphones and jewelry in public and run red lights to avoid being set upon.

"Basically, I have no social life," said Athar Shaukat, 26, an engineer.

Hiring security guards carries its own risks. Some reportedly provide information to kidnappers, fueled by greed or resentment that their clients might spend more on lunch than on their monthly wages.

"You have to have a guard," said Noman Zafar Mirza, Karachi-based director of Zims Security, who added that they're also something of a status symbol. "But we're seeing a danger here. They know your home address and a lot about you."

Fueling this social tension is a growing economic divide. In recent years, impoverished migrants have flooded Karachi from the restive northeast, fleeing villages where U.S. drones operate and government often doesn't. The influx has expanded the city's residents by 80%, the equivalent of adding New York City's population in a decade. On the main road to the airport on a recent morning, dozens of men slept under rags in the median beneath posters for "Expo Pakistan 2013," illustrated with pictures of diamond jewelry.

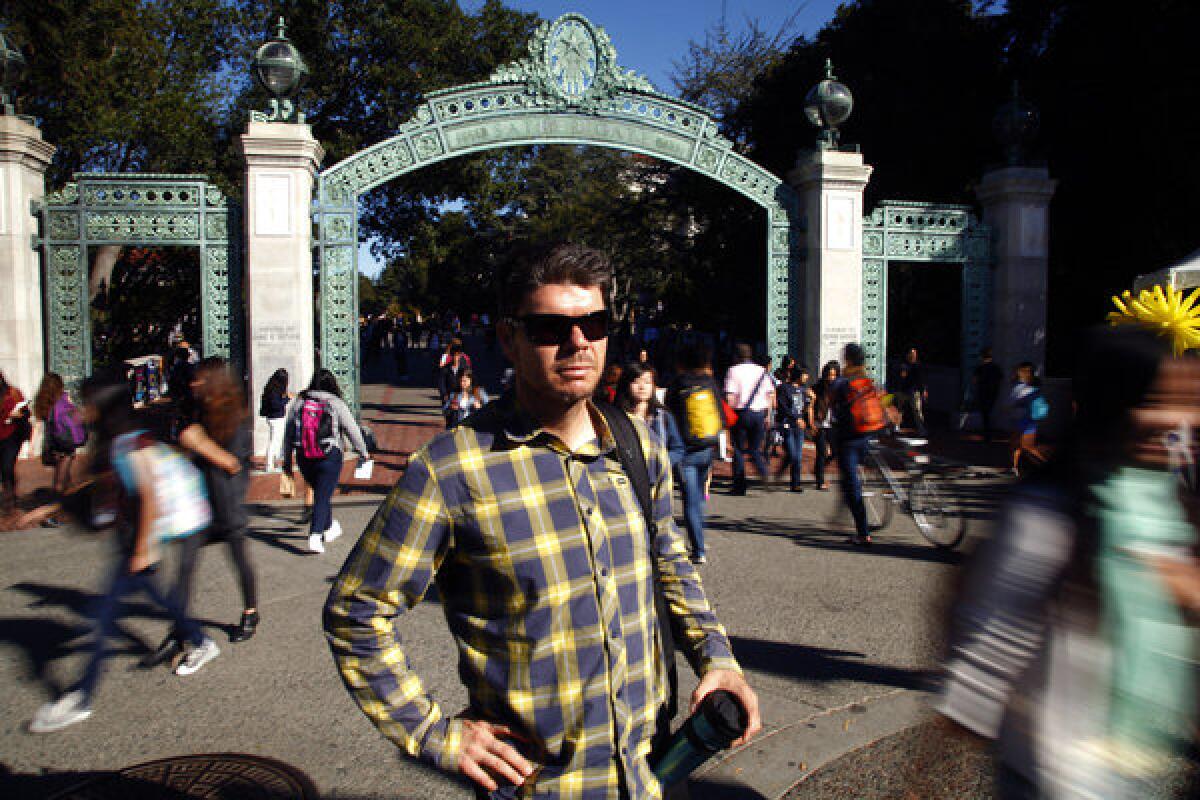

Pakistani paramilitary soldiers cordon off an area during a targeted operation in Karachi. Kidnappings for ransom, sectarian attacks and gang warfare have spiraled since 2008. (Asif Hassan / AFP/Getty Images) More photos

The latest proposal to tame Karachi involves letting security services detain suspects for 90 days without filing criminal charges, a step human rights groups oppose given the history of police and paramilitary abuses.

"It's a free-for-all," said Anjum Nisar, former president of the Karachi Chamber of Commerce. "You can't fix this by giving a Panadol. You have to go deep into the arteries."

As competition intensifies, the kidnapping business has evolved, leading to more abductions that last a day or two. Although the ransoms are lower, there's also less chance authorities will get involved — and more chance to carry out multiple kidnappings each month.

"It's better cash flow," Nisar said.

Once Qaimkhani's relatives realized that he'd been taken hostage in January 2010, they contacted a nonprofit committee that works alongside Pakistan's often-corrupt security services to help civilians cope with crimes such as kidnapping and extortion. The group, the Citizens Police Liaison Committee, was started in 1989 by businessmen tired of being targeted, and of getting little or no help from authorities.

Members of the committee trained Qaimkhani's father to act as lead negotiator for his son's release. Their advice: Wear down the kidnappers and delay without saying no.

"If you keep negotiating," said Ahmed Chinoy, head of the committee, "there's always a hope for life."

Earlier this year, Pakistani volunteers transfer the bodies of slain kidnappers to a hospital in Karachi. In a case with similarities to Saad Qaimkhani's abduction, police raided a kidnapping gang's hide-out and rescued a teenage boy being held for half a million dollars in ransom. The raid left four kidnappers dead; a fifth suspect was arrested. (AFP/Getty Images) More photos

As advised, Qaimkhani's middle-class family pleaded poverty — heavily mortgaged house, leased cars — to buy time.

In two subsequent calls, the kidnappers' price fell to $28,000, still more than the family said it could afford.

All the while, Chinoy's crew was gathering intelligence via informants, cellphone records and voice-recognition software.

Qaimkhani's kidnappers didn't seem smooth enough to be from one of the big gangs whose well-planned operations target the rich. It was more likely one of the amateur groups that pick their targets randomly, Chinoy theorized.

The committee, along with police, narrowed down the kidnappers' location, deploying agents in the neighborhood who posed as street vendors, fruit sellers and motorcycle riders — less obvious than people in cars — to watch houses and ask questions.

When police finally raided the house where Qaimkhani and his friend had been held, the young men were gone. They had been moved by the kidnappers at the last minute. But within hours, authorities found the two in a nearby house. Qaimkhani recalls hearing a loud knock on the door, followed by a short pause and then an explosion of gunfire.

It’s always in the back of my mind. But at least I’m not so afraid to go outside now."— Saad Qaimkhani

As bullets passed through the walls near their heads, the two dived into a corner. "I thought, this is it," Qaimkhani said.

One kidnapper was killed in the gunfight and the two others were arrested. A few minutes later, Chinoy handed Qaimkhani a cellphone and he heard his father's voice. "The feeling was amazing," Qaimkhani said. "I'd been given a second life."

Still, the psychological scars run deep. He's received invaluable support, he says, from two cousins who were kidnapped before he was, and his family calls every few hours when he's out and never lets him travel alone at night.

"It's always in the back of my mind," he said. "But at least I'm not so afraid to go outside now."

Follow Mark Magnier (@markmagnier) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Murder or mercy for woman with disability?

Who are the people ... vulnerable to being thought better off dead and how do we protect them?"

From prison isolation to a sense of doom

Nothing bad is going to happen ... but I still feel like there is an imminent threat."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.