A chronicle of loss at Brazil’s National Museum, much of which was destroyed by fire

Reporting from SAO PAULO, Brazil — The losses could be incalculable, an entire chapter of a country’s culture and history gone up in flames.

Brazil’s Museu Nacional, the largest natural history museum in Latin America, was consumed by fire Sunday night, a jarring sight in this prideful nation. Founded by Joao VI 200 years ago, the museum was the country’s oldest and one of its most important, housing an archive of 20 million scientific and historical items, most of which are believed to have been consumed in the blaze.

The cause of the fire has not been determined, but funding cuts and inadequate maintenance already are being blamed. Upkeep at the museum had long been neglected, evident by peeling walls and exposed electrical wires. In 2015, the museum was briefly closed to the public because of what it called “problems with security and cleaning services.” Salaries hadn’t been paid in months.

The federal government has been accused of ignoring pleas for help from Museu Nacional for years, and thousands of protesters turned up outside the museum Monday, blaming President Michel Temer’s austerity measures for the loss of so much history. The president has described the damage as “a sad day for all Brazilians.”

Here are some gems of the Museu Nacional that may be lost:

Luzia Woman

At about 11,500 years old, Luzia Woman is believed to be the oldest human skeleton ever found in the Americas. Discovered in a cave in Brazil in 1975 by French archaeologist Annette Laming-Emperaire, the origins of the upper Paleolithic period skeleton caused great debate. Some anthropologists thought her skull suggested her ancestors were from Southeast Asia.

Scientists in 2010 created a reconstruction of her face, which was also on display at the museum. Neither the Luzia Woman fossil nor the replica have been found, though remnants may be hidden in the still-unexplored rubble at the base of the museum.

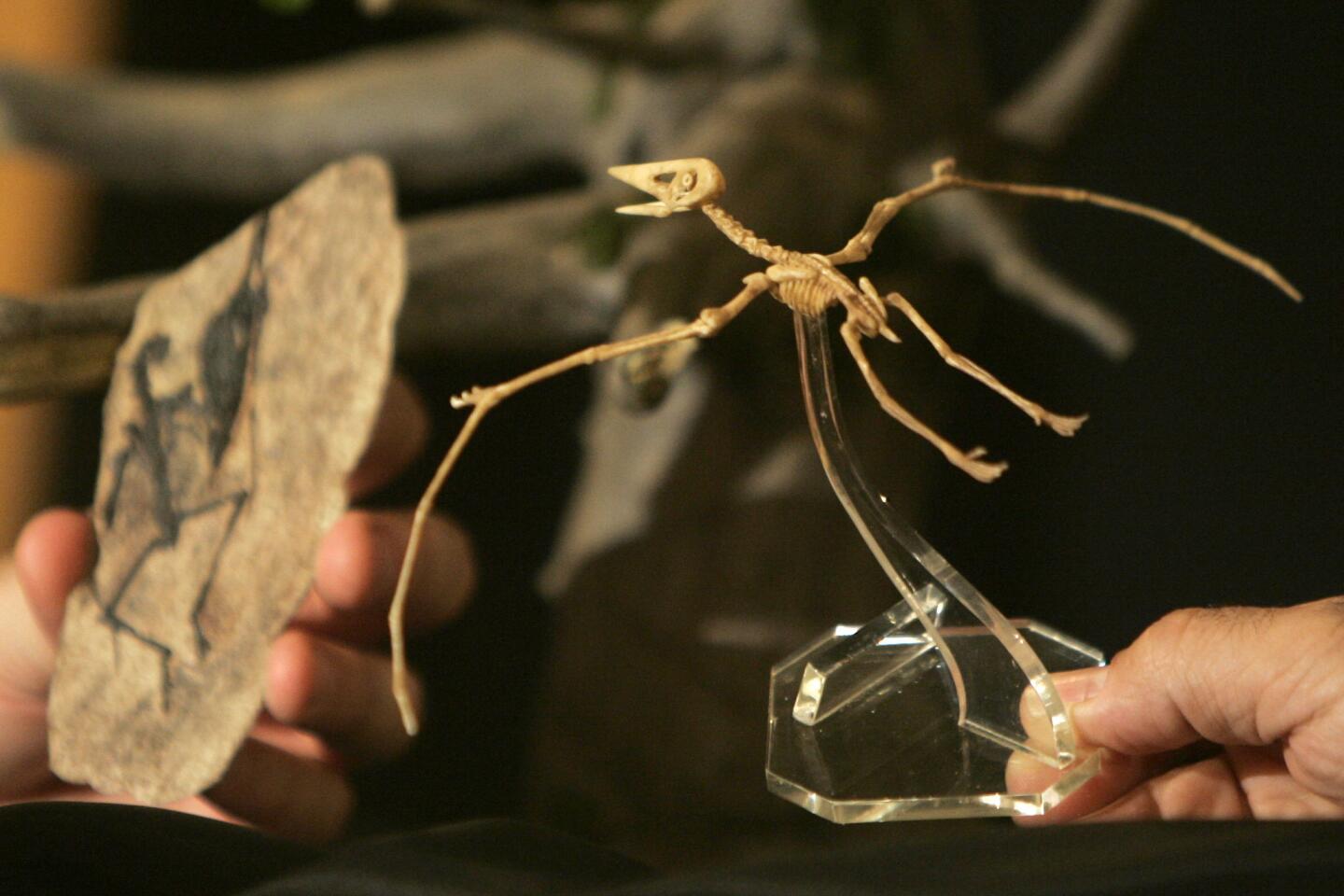

Fish-eating dinosaur

The Angaturama limai dinosaur had a long cranium and a jaw line similar to that of the modern-day crocodile, which led paleontologists to believe it spent most of its time in the water searching for food. A fish-eating carnivore known for what looked like a sail on its back, its genus name, Angaturama, was derived from the indigenous Brazilian Tupi language, meaning noble, while its species, limai, was chosen in honor of the late researcher and paleontologist Murilo Rodolfo de Lima. Fossils of its closest relatives have been found both in Brazil’s Maranhao state and in Africa, supporting the theory that South America and Africa were once one continent.

The museum’s expansive fossil collection also included a replica of a Maxakalisaurus topai dinosaur skeleton, the largest scientifically identified sauropod found in the country, and fossilized turtles from 110 million years ago. Fossils of brachipods, invertebrate animals abundant in the Paleozoic era, were also housed at the Museu Nacional. They were the first fossils of the Devonian period, about 390 million years ago, and were collected and studied in Brazil in 1870.

Francisca Keller Library

The Francisca Keller Library belongs to the postgraduate program in social anthropology at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, which has ties to the Museu Nacional. Founded in 1975, it had the most complete collection of anthropological literature in Brazil and one of the most important in Latin America, including more than 37,000 books, leaflets, periodicals, maps, theses, dissertations and other rare works.

The museum also had its own separate library, which specialized in natural sciences and anthropology. Its collection of rare items was digitized in 2008 and now can be accessed online. The actual material, though, is now probably gone.

Memory and Archive

The Memory and Archive section of the Museu Nacional had a collection of documents that recorded the beginnings of scientific work in Brazil and the changes that occurred in the world of international science. It also housed the private personal collections of several noted scientists and professors.

Among the documents that were probably destroyed in the fire is the original creation decree of the Museum Library from July 11, 1863, signed by then-Minister of the Empire Pedro de Araujo Lima, the marquis of Olinda.

Indigenous languages center

Formally created in 2004, the center specialized in indigenous languages and the various dialects of Brazilian Portuguese, with a collection of text, sound and visual materials.

Books on linguistic theory, indigenous education, anthropology, archaeology, literature and philosophy are already available online. But the tapes, CDs, photos, negatives and videos that gave researchers direct access to primary data on these languages, including narrative discourse, songs and vocabularies, were all probably destroyed in the fire.

Indigenous art and artifacts

Irreplaceable art and objects from Brazil’s many indigenous peoples were also housed in the Museu Nacional were probably destroyed.

Feather art and ceramics from the Karaja people, of which there are only about 3,000 left in central Brazil, were displayed in the museum. A collection of about 1,800 items from the Columbian era, including artifacts from the Inca and Nazca civilizations, were were probably burned too, as was the mummy of a Chilean man estimated to be at least 3,500 years old.

Egyptian collection

The coffin of Sha-Amun-em-su, dated around 750 BC, was given to former Brazilian monarch Dom Pedro II on his second visit to Egypt, and remained in his possession until Brazil became a republic in 1889. Since then, it was displayed in the Museu Nacional. It has never been opened, but X-rays show that, along with the body, there are amulets still intact inside the painted wooden coffin.

The museum held about 700 other Egyptian items, including a mummified cat and the coffin of the priest Hori, said to be 3,000 years old.

Frescoes from Pompeii

Frescoes that were originally part of the Temple of Isis in Pompeii were probably consumed in the fire, including one with two peacocks perched on stylized chandeliers and two others depicting seahorses and a dragon with a snake’s body, both flanked by dolphins.

The museum’s Mediterranean collection contained 750 items, making it one of the largest in Latin America.

Jill Langlois is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.