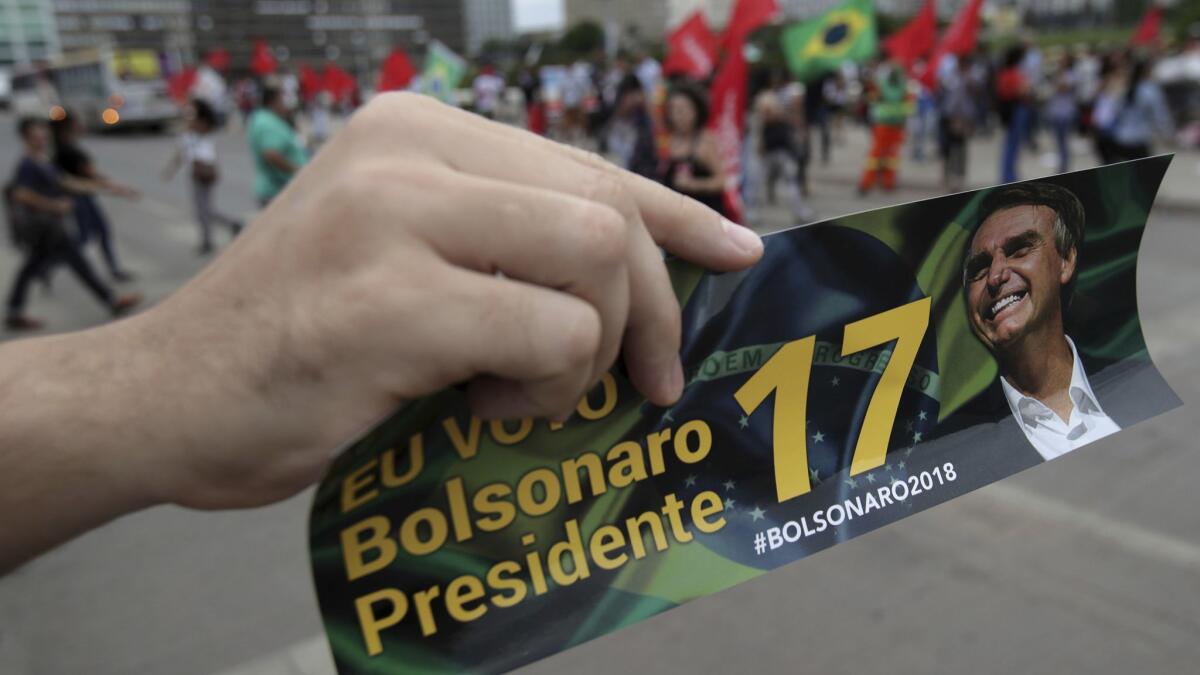

Brazil presidential candidate fires off insults, praises dictators

Reporting from SAO PAULO, Brazil — He is a bombastic candidate whose politically incorrect tirades have fired up a base of loyal supporters.

His campaign stands accused of propagating fake news and unleashing violence.

Much of the press, academics and the political establishment find him repugnant.

And on Sunday, Brazilians are expected to make Jair Bolsonaro their president.

Polls predict that he will win 57% of the vote.

Comparisons to President Trump have been unavoidable, as the Brazilian intelligentsia struggles to understand how such an unorthodox figure — a man who has praised the country’s old military dictatorship and told minorities to “shut up” and “fall in line with the majority” — has managed to hijack the political system.

A big part of the answer is crippling unemployment amid a deep recession and a billion-dollar corruption scandal known as Car Wash, in which top politicians and business elite have been accused, charged and jailed for money laundering and other crimes.

Many voters say Bolsonaro is the only way the country will get a fresh start. Despite the former army captain’s almost 30 years as a congressman, he is seen by many as an alternative to the old political class.

“Bolsonaro provides a sense of direction, protection and order,” said Oliver Stuenkel, a professor of international relations at the Getulio Vargas Foundation. “Brazil has been facing a triple crisis over the past few years: A profound economic crisis — one of the worst in the country’s history. A profound political crisis with no normal sense of being governed since 2013. And the perception of a moral crisis because of massive corruption scandals.

“The estrangement that Brazil’s society is feeling toward its institutions is so profound that somebody who can speak directly to people and who is adopting a different rhetoric has been able to find support,” he said.

It also helps Bolsonaro, of the right-wing Social Liberal Party, that his opponent is the last-minute candidate of the scandal-plagued Workers’ Party.

Fernando Haddad was little known outside Sao Paulo — where he served as mayor from 2013 to 2017 — before late August when a court ruled that the party’s preferred candidate, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the once wildly popular president, is ineligible to run from prison, where he is serving a 12-year sentence for accepting $1.2 million in bribes from a contractor.

As a substitute, Haddad finished second to Bolsonaro in the first round of voting this month. In a field of 13, Bolsonaro took 46% of the vote while Haddad took 29%.

Haddad, a former philosophy professor, has campaigned on promises to expand programs to combat hunger and create affordable housing, improve public security, and combat economic inequality by taxing the rich more and the poor less.

But his allegiance to his party, which led Brazil from 2003 to 2016, is too much of a reminder of the past for many voters.

Lula dramatically reduced poverty and had an approval rating of 87% when he left office. But corruption scandals eventually consumed the party. His successor, Dilma Rousseff, was impeached and convicted by senators of breaking Brazil’s fiscal responsibility law.

“The Workers’ Party has ruined this country,” said Alexandre Goncalves, who owns a small constructions supply business in Rio de Janeiro. “The only thing that will make our situation worse is voting them in again. They’re all corrupt.

“I voted for Bolsonaro the first time and I’ll vote for him again,” he said. “He’s honest and might actually do something for Brazil. He says a lot of crazy things, but he’s not actually going to do any of them. He’s just joking to get people’s attention.”

He has certainly succeeded in that regard.

Bolsonaro has called Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra — a known torturer from the military dictatorship that ruled the country from 1964 to 1985 — a “Brazilian hero” and said the country’s biggest mistake during that era was not killing 30,000 more people.

He has said he would rather have a dead son than one who was gay and that one congresswoman didn’t deserve to be raped by him because she was “very ugly,”

On the campaign trail, he advocates for looser gun laws. Visiting a shooting range in Miami last year, he suggested that Brazilian police officers should carry .50-caliber handguns so they could kill suspects with one shot only and avoid being accused of excessive force.

His plan to boost the economy includes kicking indigenous people off their land to expand agribusiness. He has said that “minorities have to shut up, to fall in line with the majority,” and he told a crowd of cheering supporters in Acre state to “gun down the petralhada,” a reference to the Workers’ Party.

Many voters are dumbstruck that so many of their compatriots would support Bolsonaro.

“Anybody is better than Bolsonaro,” said Gisele Sanches, a cashier at a pharmacy in Sao Paulo who planned to vote for Haddad. “The Workers’ Party has its problems, but at least it’s not out to kill anybody.”

Bolsonaro’s rhetoric has been widely blamed as a factor in a wave of political violence.

The Brazilian investigative journalism organization Publica released a report on Oct. 10 that showed at least 71 politically motivated violent attacks occurred between Sept. 30 and Oct. 10. Of those attacks, 50 were attributed to supporters of Bolsonaro.

The violence included the killing of Romualdo Rosario da Costa, a capoeira master. It was the day of the first round of voting, and he had cast his ballot for Haddad. He was sitting in a bar with his brother and a cousin when a man named Paulo Sergio Ferreira de Santana interrupted them and offered his political opinion.

Santana, who said he voted for Bolsonaro, paid his bill and left, but returned minutes later and stabbed Costa in the back 12 times.

“The advent of a candidate who preaches hatred, who normalizes violence and who preaches gun use leaves people feeling empowered to be violent in the name of their individual beliefs,” said Natalia Aguiar, a political scientist at the Federal University of Minas Gerais.

Bolsonaro too has been a victim of violence. During a campaign rally, he was stabbed in the abdomen by a man who told police that God told him to do it and has since been charged under Brazil’s National Security Law with committing a politically motivated assault.

That only boosted his standing in the polls.

Even after doctors cleared him to start campaigning again, Bolsonaro has limited the time he spends in public.

He shuns news conferences and instead speaks to voters through Facebook Live videos and the chat program WhatsApp.

Several entrepreneurs who have been bankrolling his campaign were recently accused of bombarding users on the popular chat app with hundreds of millions of messages containing false claims about Haddad.

The scandal doesn’t appear to have hurt Bolsonaro.

“They say he is the one spreading the fake news, but it’s obvious now that he’s the target,” said Yara Andrade, a manicurist in Sao Paulo who planned to vote for him Sunday. “He wouldn’t lie. He’s an honest family man and he’s going to turn this country around. He’s what we need right now.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.