A genocide overlooked: A Catholic priest works to bring attention to the mass killings of Yazidis

As he watched the television images of terrified Yazidi women and children fleeing Islamic State militants in northern Iraq, a familiar unease gripped Father Patrick Desbois.

There were no men among the fleeing villagers. This, he told himself, was genocide unfolding before his eyes.

Though Desbois had never heard of the Yazidi, the 2014 images stirred a spiritual calling to investigate the mass killings and other atrocities inflicted on this non-Muslim religious minority and raise awareness of a little-known ethnic group that has suffered so profoundly.

Islamic State, also known as Daesh, its Arabic acronym, killed an estimated 5,000 Yazidi men when it took control of Iraq’s northwest two years ago, according to the United Nations and human rights groups. Thousands of Yazidi women and children were taken captive. The women were often raped and sold as sex slaves or servants; the boys were forced to convert to Islam and become soldiers of Islamic State.

While the Yazidi stronghold of Sinjar has since been liberated, about 3,500 women, girls and some men remain captives of Islamic State, according to a recent United Nations report. The majority are Yazidis. The abuses, the report suggests, “may amount to war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.”

The priest pursues his calling

Desbois had already built a reputation as a self-made mass murder sleuth. Through Yahad-In Unum, the organization he founded in 2004 to uncover and denounce genocide, he had identified largely unrecognized sites where the Nazis slaughtered and buried Jews and Roma, also called Gypsies, in the former Soviet Union.

But the murderous treatment of the Yazidis presented a real-time cause.

“I couldn’t just stay on the mass killings of the past,” said Desbois, 61, a former mathematics teacher and government worker. “But I had no door to enter into Iraq.”

That opening arrived unexpectedly. On business in Brussels in the winter of 2015 and searching for a barber, Desbois stepped into the only open shop he could find — one run by Arabs. When the priest told the barber that he was interested in learning more about the tragic Yazidi situation, the man whispered in his ear that he was a Yazidi.

The barber and his family helped initiate the primary contacts that Desbois needed to begin his mission, and two months later the priest was en route to northern Iraq.

Documenting genocide

Today, through a project called Action Yazidis, Desbois collects testimony from survivors who escaped slavery and imprisonment by Islamic State. The accounts are pieced together through interviews that are cross-referenced with separate statements, photographs and other sources and written material.

Every nugget of information comes from the victims: What day, date and time did the Islamic State fighters arrive? Where exactly were you — in the house, in the yard, at school? Were you alone? Who was with you?

The survivors are asked to draw details of what they remember: An illustration of the camp where they were held, where they entered, whether they could sit down, the number of seats. The interviews last hours.

The goal is not only to document the horrors but also “to rebuild the topography from the first day of being captured to the day of escape,” Desbois said.

Each story paints a grim picture of Islamic State’s methodology. The militants typically arrive toting three bags: one to collect money from their captives, one for jewelry and the third for cellphones. Desbois was familiar with the tactic; the Nazis also stole from their victims.

Families are separated. Newborns are taken from mothers and given to Muslim families. Boys, many as young as 9, are taken to prison, forced to convert to Islam and sent to terrorist training camps to learn to shoot Kalashnikov rifles, fire rockets and — if necessary — blow themselves up.

Girls are examined to determine whether they have entered womanhood, Desbois said. Virgins are sold to the highest bidder. Young mothers are forced to become servants. Older women are saved for use as human shields against attacks.

“In Daesh everyone has a purpose,” Desbois said.

The effects of the terror and abuse

One 42-year-old woman who spent almost two years in Islamic State captivity with her four children recalled one fighter breaking her 6-year-old son’s teeth and laughing at him, and then hitting her 10-year-old daughter so hard she urinated.

“He would beat my children up and lock them up in a room,” the woman told Amnesty International. “They would cry inside and I would sit outside the door crying. I begged him to kill us, but he said he didn’t want to go to hell because of us.”

Her account, as those of 17 other women and girls who survived Islamic State captivity, was published in a recent Amnesty International report that concludes victims are in desperate need of financial assistance and psychological counseling.

Last year, dozens of Yazidis committed or attempted suicide in northern Iraq’s Kabarto refugee camp, according to Alex Bartoloni, Baghdad-based community health manager for the International Medical Corps, a Los Angeles humanitarian medical group.

“We had never seen this level of suicide in another refugee population,” said Bartoloni, whose group provides mental health and psycho-social support for about 30,000 displaced Yazidis in the camp. “It was quite shocking to us.”

Although the suicides have decreased in recent months, Bartoloni said the level of anxiety, depression and extreme distress had “taken a large toll on family dynamics.”

Justice delayed by international inaction

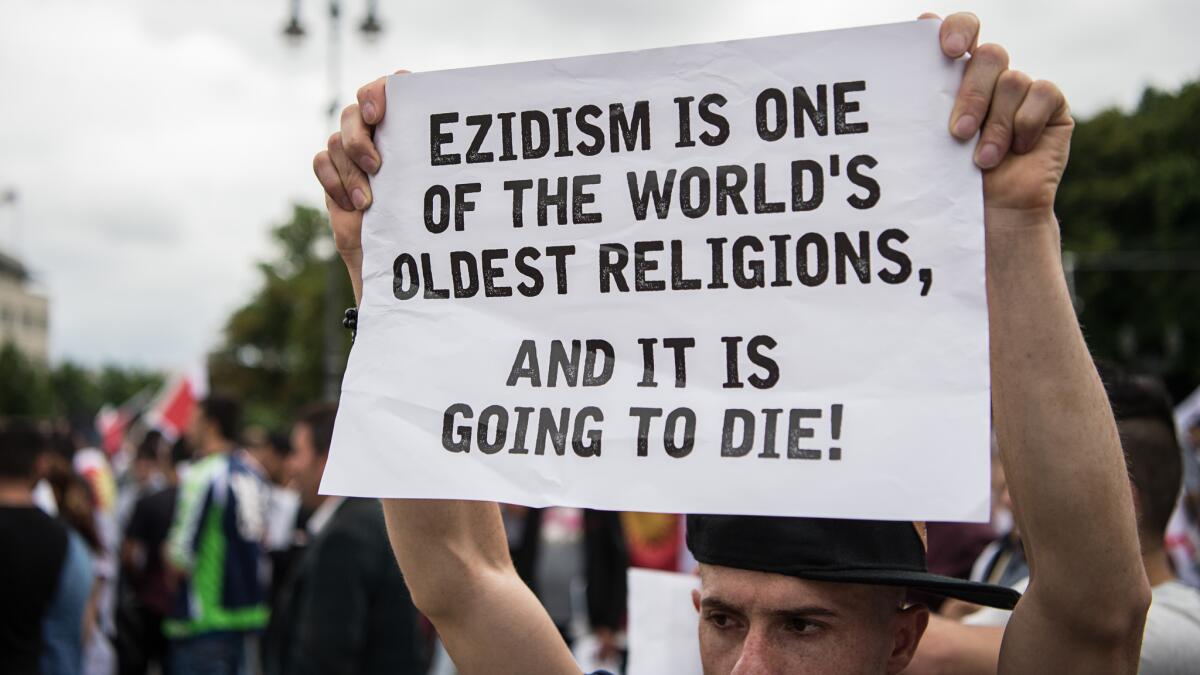

Among the Yazidis, there is a sense the world has turned its back on them. Or, worse, is not even aware of what is happening.

Mirza Ismail, chairman of the Canada-based Yezidi Human Rights Organization-International, called on people in the West to press their governments “to stand for accountability and justice.”

Ismail’s group wants the world to acknowledge that Yazidis, a predominantly ethnic Kurdish religious minority that is widely believed to have suffered 74 genocides throughout its history, are being targeted solely because they are non-Muslims.

“What has the West done to save the non-Muslim minorities, if anything at all?” Ismail asked.

Gulie Khalaf, treasurer of Yezidis International, a nonprofit based in Lincoln, Neb., which is thought to have the largest Yazidi population in the U.S., stressed the importance of survivors keeping their stories alive by sharing testimony.

“They are documents to help study and understand what happened and how and why we failed to protect hundreds of thousands of people,” said Khalaf, whose group works to educate the public about the Yazidis. “It holds the authorities accountable for their actions and future action. It helps lawmakers make better decisions for prevention of genocides.”

Desbois said the first step toward justice is capturing and punishing Islamic State leader Abu Bakr Baghdadi, who has exploited the world’s seeming indifference toward the plight of the Yazidis.

“If we begin not to care about the genocide of people we don’t know about, we open the door for much worse,” Desbois said.

For more on global development news, follow me @AMSimmons1 on Twitter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.