Putin’s best friend is at the heart of Panama Papers scandal

A 2009 photograph shows Russian cellist Sergei Roldugin, left, and his close friend Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Reporting from Moscow — Sergei Roldugin is Russian President Vladimir Putin’s closest friend. They met when Putin was training to become a KGB officer at school, where Roldugin’s brother was one of Putin’s classmates. Roldugin introduced Putin to his future wife, Lyudmila, and the couple made him the godfather of their eldest daughter in 1985.

“He is simply like a brother to me,” Roldugin said in Putin’s biography, “From the First Person,” published in 2000 just months after Putin assumed his first presidency.

While many of Putin’s former KGB colleagues and summer home neighbors followed him to Moscow, assuming key government jobs and controlling entire sectors of the Russian economy, Roldugin stayed out of sight. The 64-year-old cellist teaches at the St. Petersburg conservatory, manages a charity that helps talented children, and occasionally conducts the orchestras of the Mariinsky opera and ballet theater that was founded by Catherine the Great.

But an investigation published Sunday suggests that Roldugin hasn’t been living such a quiet life. He has allegedly amassed a fortune of more than $100 million through three offshore companies that list him as owner, according to reports published by multiple news outlets based on a trove of leaked documents from Panamanian law firm Mossack Foncesca.

An anonymous source first leaked the documents to the Sueddeutsche Zeitung newspaper, based in Munich, Germany, last year. The newspaper partnered with news organizations around the world to report on the documents, dubbed the Panama Papers.

Roldugin has allegedly acquired a 12.5% stake in a major Russian advertising company, and holds a 3.2% stake in Bank Rossiya, the reports say. The U.S. government blacklisted the bank for its close ties to Putin.

The companies under Roldugin’s name had a turnover of $2 billion, and their income mostly came from insider deals with the stock of Rosneft and Gazprom, Russia’s largest, state-controlled oil and gas companies, according to the reports. “Donations” from Russia’s wealthiest businessmen and loans from an obscure Cyprus bank were also major sources of income.

The leaked files suggest that Roldugin is not keeping this wealth for himself, but is funneling the money to Putin’s inner circle, the reports say. Although Putin is not mentioned in the documents, he appears to be at the center of a web of Russia’s most influential and powerful men who owe their posts and fortunes to nothing but their friendship and association with him.

“It’s possible Roldugin, who has publicly claimed not to be a businessman, is not the true beneficiary of these riches,” the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists wrote. “Instead, the evidence in the files suggests Roldugin is acting as a front man for a network of Putin loyalists -- and perhaps for Putin himself.”

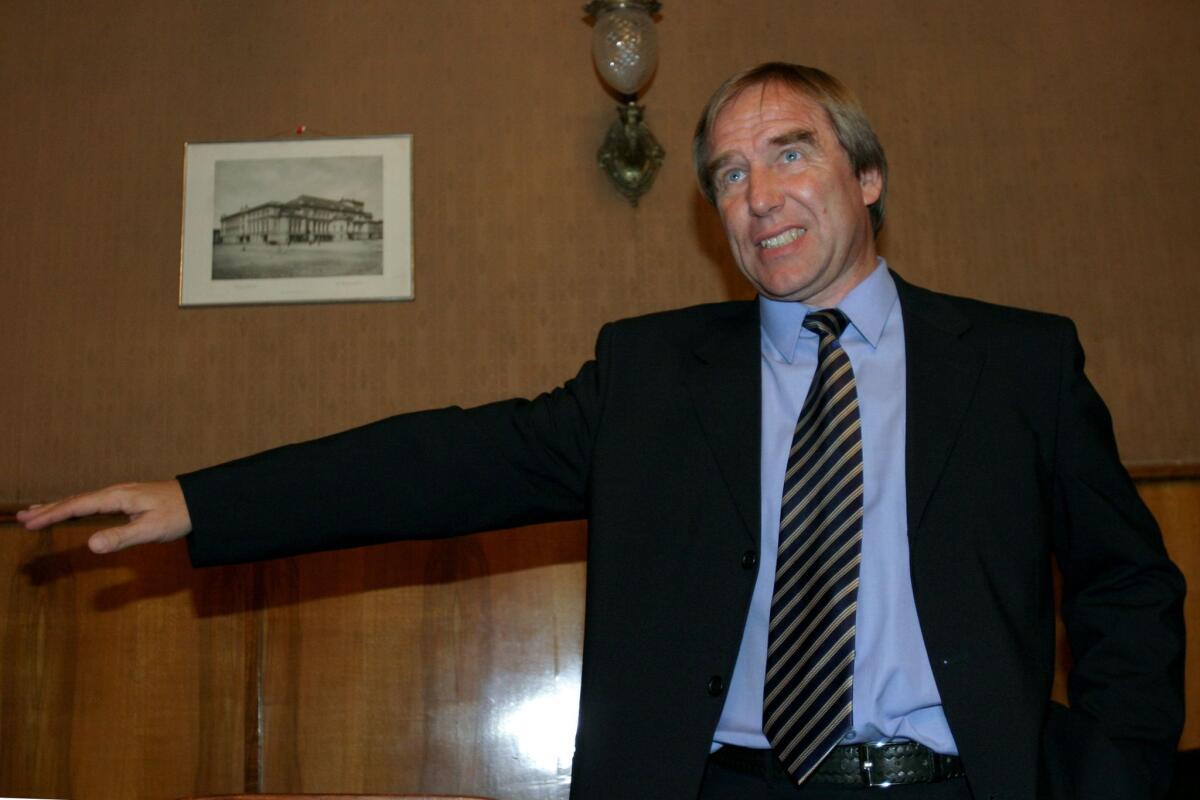

Cellist Sergei Roldugin speaks with the media in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 2000.

Roldugin is not the only friend and confidant of Putin’s mentioned in the Panama Papers. The reports mention Putin’s judo sparring partners, the wives of Putin’s spokesman and a governor, sons of economy and deputy interior ministers, four Russian lawmakers and several members of the ruling United Russia party.

But Roldugin seems to be the only person mentioned in the Panama Papers who has directly responded to the accusations against him. Novaya Gazera, one of Russia’s last remaining investigative newspapers that participated in the Panama Papers investigation, approached the cellist after a concert in Moscow on March 24.

“Honestly speaking, I can’t comment on this,” Roldugin was quoted as saying. “I have to see and understand what I can say and can’t. I am simply afraid to be interviewed.”

“Where’s the money from? Whose [money is it]? I know all that. These are delicate matters,” he told the Novaya reporter, promising to come back with a more detailed response. But he never did -- and stopped answering his phone, the paper said.

Russian officials: Panama Papers scandal is a Western plot against Russia

Russian officials met the Panama Papers investigation with rare and angry remarks that follow a popular conspiracy theory -- propagated in recent years by Kremlin-controlled television -- about the evil West plotting against resurgent Russia.

Putin’s spokesman Dmitri Peskov said that the reports “lack details.”

“The rest is based on arguments and speculations. We don’t want to and will not respond,” Peskov told Russian news agencies. “Putinophobia has reached such a degree that one cannot say anything good about Russia a priori.”

Last week, Peskov said that a major “information attack” on Putin is expected, and his warning seems to have stifled any upcoming domestic coverage.

No major television network or state-controlled media outlet covered the Panama Papers. Monday news shows on Kremlin-controlled television networks covered a deadly fire in a Siberian city, doping scandals in the United Kingdom, the Syrian war and the migrant crisis in Europe.

A top anti-corruption official called the report part of a smear campaign against Russia.

“The number of information attacks on Russia’s president and the simplicity of the lies-filled reports are like multiple injections of poison -- hopefully, at least one of them will work,” lawmaker Irina Yarovaya told the Itar-Tass news agency.

The Kommersant, an influential Russian daily, published a small commentary by its economy expert.

“The researchers failed to find direct confirmation of corrupt deals neither for Russia nor for Ukraine, or for other countries in the databases,” Dmitry Butrin wrote.

The newspaper, once one of Russia’s most respected independent publications, is now owned by Alisher Usmanov, a powerful tycoon with close ties to the Kremlin.

The CEO of one of Russia’s largest state-run banks, vehemently defended the Russian president.

“Mr. Putin was never involved. It’s [garbage],” VTB’s Andrey Kostin told Bloomberg. “There’s definitely quite a big campaign” against Russia.

A blow to Putin’s reputation?

Russian opposition figures were hopeful that the Panama Papers revelations would tarnish Putin’s image. “The report is based on the leaked data from just one of Panamanian law firms,” opposition leader and anti-corruption crusader Alexei Navalny said in statement. “Yet, this small part is good enough for [Putin’s] impeachment.”

Navalny cut his teeth as the author of detailed reports on corruption among Russian officials, including Putin’s closest friends. He recently called Putin a “czar of corruption.”

His latest investigation, a YouTube video accusing Russia’s prosecutor general, Viktor Chaika, of having ties to organized crime and corrupt businesses, has been seen more than 4.7 million times since its release in December -- or slightly more than 3% of Russians.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, center, poses for a selfie with SKA hockey club president and KHL board member Roman Rotenberg, left, and businessman Gennady Timchenko, second from right, last May.

An opposition lawmaker who was kicked out of Russia’s lower house of parliament for his criticism of Putin and United Russia said that the report has dealt a “serious blow” to Putin’s reputation. It will “contribute to the destruction of his image of an infallible president, and all the power, all the might of the government are based on Putin’s personal image,” Gennady Gudkov said.

Transparency International, an international anti-corruption watchdog, called the Panama Papers a “pleasant surprise.”

“All of this roughly coincides with what we have been dealing with,” said Anton Pominov, head of the Russian branch of Transparency International. “This is a pleasant surprise that documents of this kind surface in such quantities and with such quality.”

“There are dozens of such companies, and there’s many more offshores, and the scope [of such schemes] could be dozens of times bigger,” he added.

The group said in January that Russia ranks 119 in its global corruption index of 167 nations, between Guyana and Sierra Leone.

The Kremlin’s resurgent propaganda machine and a crackdown on independent media will keep most Russians ignorant about the Panama Papers, according to Levada Center, a Moscow-based independent pollster.

“No more than several percent of the population will learn about it,” said Levada sociologist Denis Volkov.

He said that no more than 15% of Russians knew about Russian opposition’s reports on corruption among top officials -- and added that average Russians “didn’t move beyond” the archetypal Russian idea of a “good czar” who fights corruption among his officials but is himself devoid of any wrongdoings.

“Mostly, Putin is excluded from these schemes, Putin is fighting them, although without success,” Volkov said.

Over the last decade, numerous reports by Russian and international media outlets, anti-corruption groups, opposition and critics accused Putin’s inner circle of involvement in massive corruption schemes worth billions of dollars.

The Guardian claimed in 2007 that Putin owned a fortune of “at least” $40 billion, citing political analyst and former Kremlin insider Stanislav Belkovsky.

Putin responded to the report with one of his trademark salty phrases. “They have picked this in their noses and have smeared this across their pieces of paper,” he told a news conference in 2008.

Opposition leader Boris Nemtsov published a series of reports on Putin’s implication in corruption, money-laundering and illegal businesses.

“Corruption in Russian ceased to be a problem and became a system,” he wrote in one of his reports.

Nemtsov described “The Lake Cooperative,” a group of several ex-KGB officers and close friends of Putin who built modest dachas, or country houses, outside St. Petersburg, becoming Putin’s neighbors.

After Putin’s rise to the presidency, the cooperative’s members -- along with Putin’s former colleagues and judo sparring partners -- rose too.

Within years, they became top officials in charge of Russia’s security, interior affairs, transportation, customs service, communications, migration service and anti-drugs enforcement.

Others turned into Forbes-listed tycoons controlling huge chunks of Russia’s oil and gas exports, railroads, nuclear fuel supply, hi-tech sector, gas pipeline construction, telecoms, advertising and banking, Nemtsov’s report said.

Most of the officials listed in Nemtsov’s report have not denied their friendship or collegial ties with Putin that precede his presidency.

Nemtsov was killed outside the Kremlin walls in 2015.

In 2014, the New York Times said that Bank Rossiya--– in which cellist Roldugin allegedly owns a stake -- had some $11 billion in assets and spread its “tentacles” across Russia’s economy.

The bank became a symbol of Putin’s “brand of crony capitalism” that allowed his friends and former colleagues to become billionaires who control key sectors of Russia’s economy, the report said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.