Ties between the U.S. and Philippines run deep. It won’t be easy for Rodrigo Duterte to unravel them

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, 71, passed his 100th day in office on Oct. 8.

Reporting from Beijing — Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte arrived in China this month and declared his “separation” from the United States. Then he went to Japan and threatened to kick American troops out of his country, throwing the future relationship of two longtime partners into doubt.

His rancor tests one of America’s most crucial alliances in Asia. Duterte’s comments stoke indignation about U.S. treatment of its former colony, but they also discount deep economic and military bonds — ones that would prove difficult for the tough-talking leader to unravel.

“It’s quite hard to underestimate the depth and complexity of the relationship,” said Malcolm Cook, a senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore.

“The harm would be much more on the side of the Philippines than the U.S.”

How close are the two countries?

The U.S. is the nation’s second-largest trading partner after China and one of its biggest foreign direct investors. A predominately Catholic population has absorbed America’s fast food, basketball and pop culture.

More than 90% of Filipinos regard the U.S. favorably, according to a 2015 Pew Research Center survey, a larger percentage than any other country polled — including the U.S.

That relationship extends to California, which holds the majority of some 4 million Filipinos and Filipino Americans who live in the U.S. The money they send back makes up nearly half of all remittances from overseas Philippine workers. Total payments home contribute about one-tenth of the nation’s gross domestic product.

The U.S. provides some equipment and training for the military, and American troops have helped fight Islamic separatists in the southern Philippines. A defense treaty affirming support against outside attacks dates back nearly seven decades.

“It’s clear Duterte’s special sensitivities to the U.S. may not be shared by the vast majority of Filipinos,” said Gerard Finin, director of the East-West Center’s Pacific Islands Development Program in Honolulu.

What are the origins of this relationship?

The U.S. paid Spain $20 million for the Philippines in 1898 following the Spanish-American War. The purchase drew the U.S. into an ongoing battle with Philippine rebels over independence. The violence led to tens of thousands of Filipino solider deaths and, in some instances, massacres of women and children. Then-Indiana Sen. Albert Beveridge justified the conflict when he said the U.S. had a duty to civilize “a barbarous race.”

Relations improved during World War II when American Gen. Douglas MacArthur helped rid the nation of Japanese invaders. Soon after, the U.S. granted the Philippines independence.

But left-leaning nationalists like Duterte, a former prosecutor and populist mayor, believe America has failed to atone for its conquests. Some still seethe at its support for autocratic ruler Ferdinand Marcos, which allowed the U.S. to operate its largest overseas military bases: Clark Air Base and Subic Bay Naval Base.

The next government eliminated foreign military bases.

Philippines’ foreign minister, Perfecto Yasay, in September demanded the U.S. stop viewing the nation as its “little brown brother,” a reference to the term used for Filipinos when Americans controlled the island.

Some think “it’s time for the U.S. to wake up and not treat the Philippines as a doormat … but more maturely as a friend,” said Eduardo Araral, vice dean of research and associate professor at the National University of Singapore’s public policy school.

What could a breakdown in relations mean for the U.S.?

The U.S. considers the Philippines a vital partner in the face of China’s swelling ambitions, particularly in the South China Sea.

Duterte’s recent call to evict American troops takes aim at a 2014 agreement, which allows the U.S. to return soldiers to five Philippine military bases. The deal offered the Obama administration a strategic spot to boost its Asia Pacific influence, a move Chinese leaders view as an attempt to contain it.

Duterte’s predecessor, Benigno Aquino III, inched closer to Washington out of fears about China’s assertiveness in the contested waterway. An international tribunal this summer ruled in favor of the Philippines and invalidated China’s claims to the South China Sea. But Duterte has downplayed the decision, instead connecting himself with the communist country’s “ideological flow” on a recent visit and signing a whirlwind of trade deals.

“China is the clear winner in this,” Araral said.

The apparent realignment also may benefit its Southeast Asian neighbor. Philippine officials on Friday said China appears to have stopped blocking Filipino fishermen from entering waters near the disputed Scarborough Shoal.

But analysts caution against reading too much into posturing from a president new to foreign policy and just four months into office.

Duterte later couched his U.S. separation comments and said he wanted to maintain diplomatic ties.

Otherwise, “the Filipinos in the United States will kill me,” he said.

How is the White House responding?

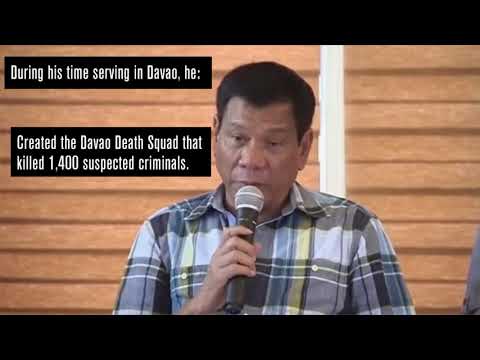

Duterte’s threats are compounded by his bloody campaign against drugs, a spate of extrajudicial killings that has left more than 3,000 dead.

The Obama administration has responded cautiously, labeling his rhetoric “troubling” and gently reinforcing a decades-long partnership.

White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest last week said the administration has received no formal indication that relations will shift.

Duterte’s comments have “injected some unnecessary uncertainty in the relationship,” he said. “It’s not indicative of the seven-decade-long alliance between our two countries. It’s not indicative of the deep cultural ties between our two countries.”

Administration officials are caught. They can respond and incite further outbursts, or wince and wait to see whether his rhetoric will spur actual changes.

“While Duterte is more talk than policy, there are going to be some policy implications,” said Richard Javad Heydarian, assistant professor of political science at Manila’s De La Salle University, “but it’s not as severe as his language suggests.”

Meyers is a special correspondent.

ALSO:

Meet the Nightcrawlers of Manila: A night on the front lines of the Philippines’ war on drugs

Philippines president cozies up to China after talking tough about the U.S.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.