Tibet’s Road Ahead: Immolations are just one sign of tension over Communist rule

Reporting From Aba, China — By the time Dongtuk arrived, the body was gone. A pack of matches lay on the ground, the only sign of the horror that had taken place. Dongtuk picked them up and fingered them.

About an hour earlier, one of the teenager’s best friends had siphoned gasoline from a motorcycle, swallowed part of it and doused himself with the rest. Then he had set himself on fire.

Standing at the scene near Kirti Monastery, where both had been apprentice monks, Dongtuk, then 17, considered the pack of remaining matches.

“At that point, I felt no doubt at all,” he said. “I wanted to die myself.”

Dongtuk’s friend, Phuntsog, was among the first of more than 140 ethnic Tibetans who have taken their lives through self-immolation, an act designed to telegraph the desperation of a people so marginalized as to have nothing left to lose.

On the cusp of the Dalai Lama’s 80th birthday, many Tibetans wonder whether their struggle for autonomy and religious freedom will soon be lost. Desperation can be seen in the number of self-immolations that have occurred since the religious uprisin

Six million Tibetans live in China, many chafing under the stifling rule of the Communist Party.

In few places are the tensions so palpable, or the resistance so stubborn, as in Aba, known as Ngaba in Tibetan. With only 65,000 people, Aba has been an outsized source of trouble for the Chinese Communist Party for almost as long as the party has been in existence.

To avoid outside scrutiny, Chinese authorities restrict visits by foreigners to Aba unless chaperoned by the government. Nevertheless, a reporter from the Los Angeles Times has visited several times in the last few years, trying to understand what made the outwardly tranquil town such an engine for unrest.

Tibetans complain that they live, essentially, as second-class citizens in their own land. Their language, culture and faith are all under pressure. They attend substandard schools and, if they manage to get an education, lack the same job opportunities as the Han, the Chinese majority.

“The town is now packed with Chinese — the vegetable sellers, the shopkeepers, the restaurant owners. They don’t speak Tibetan at all,” said Dolma, 18, whose parents are farmers and, who, like many Tibetans, uses only one name. “My parents can barely speak Chinese. When they go to town to buy things, they can barely communicate.”

Aba is located in China’s Sichuan province, outside what is known as the Tibet Autonomous Region but inextricably part of what Tibetans consider their homeland. The 10-hour drive from the provincial capital, Chengdu, follows winding canyons that eventually open up, at 12,000 feet, to grassland under a horizon-to-horizon stretch of Himalayan sky.

The town is composed of one long road, officially Route 302, although Tibetans now call it the “Martyr Road.” It is lined on both sides with red-metal shuttered storefronts — tea shops, shoe stores, businesses selling cellphones. Tibetan men wear long cloaks over their jeans; the women favor ankle-length skirts and floppy hats, with glossy black braids that cascade down their backs, and an occasional flash of coral jewelry.

Rising up like bookends on each side of Aba are gold-roofed Buddhist monasteries with white stupas, or prayer towers, that loom over the skyline. The largest, Kirti, is now known as the place people go to set themselves on fire.

After any self-immolation or protest, Aba is transformed into a military garrison. Checkpoints seal off travel in and out of town. Out come the security forces: the People’s Liberation Army and the Chinese paramilitary forces known as wujing in khaki uniforms, the SWAT teams in black and the regular police in blue.

Along with the riot shields, guns and batons, they carry another essential tool: a fire extinguisher.

Aba is a special place. Three generations have suffered from the excesses of the Chinese Communists, and their attitudes have been passed down from generation to generation.

— Kirti Rinpoche, the head of the Kirti Monastery who lives in exile in India

Huge new compounds girded by barbed wire house the police and courts. In a 2011 analysis, Human Rights Watch reported government spending on security in Aba had increased 619% between 2002 and 2009.

“You always feel like you’re being watched,” said Dawa, a widow in her 50s who lived in Aba near the Kirti Monastery until four years ago. “I was never interested in politics. I never got involved. But at the back of my mind, I never felt relaxed. I always thought I could be arrested any moment.”

Aba has a long history as a town of troublemakers. For centuries, it was ruled by tribal kings who reported neither to the Tibetan government in Lhasa nor to the Chinese. In the 1930s, Aba was the first place where Tibetans collided with Mao Tse-tung’s Red Army, which was fleeing Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists in what became known as the “Long March.”

Aba became a center of resistance in 1959, and nomads fanned out into the mountains, launching guerrilla raids on Chinese installations with ancient hunting rifles or spears fashioned by local blacksmiths. In 1966, Mao’s Cultural Revolution brought more violence. Monasteries were turned into warehouses or government buildings or demolished. Monks were forced to shed their robes and live lives for which they were ill-prepared.

The terror ended with Mao’s death in 1976. The Chinese government started rebuilding the monasteries. With the country’s economic opening, Tibetans saw their standard of living rise along with that of others in China.

Aba became famous in the 1980s for exporting entrepreneurs, who spread out across China and beyond, selling Tibetan products such as wool and medicinal herbs and introducing Tibetans to bluejeans, coffee and the Sony Walkman.

Even as they prospered, the Tibetans couldn’t help but notice the Chinese were getting even richer. And the divide grew as the government began denying travel permits to Tibetans.

“The Han people have all the advantages. All the factories are located in Han areas. We don’t have passports so we can’t travel across borders,” complained one envious businessman.

Yangchen, a rail-thin Tibetan woman in her early 30s pushing a wheelbarrow of concrete blocks up a staircase, said she was unable to find anything other than manual labor despite being able to speak excellent Chinese. Even with that, she said, the going rate for such work for Tibetans, about $16 a day, was half of what ethnic Chinese are paid.

“Most of the businesses are owned by Han Chinese,” she added, “so they naturally prefer to hire other Chinese.”

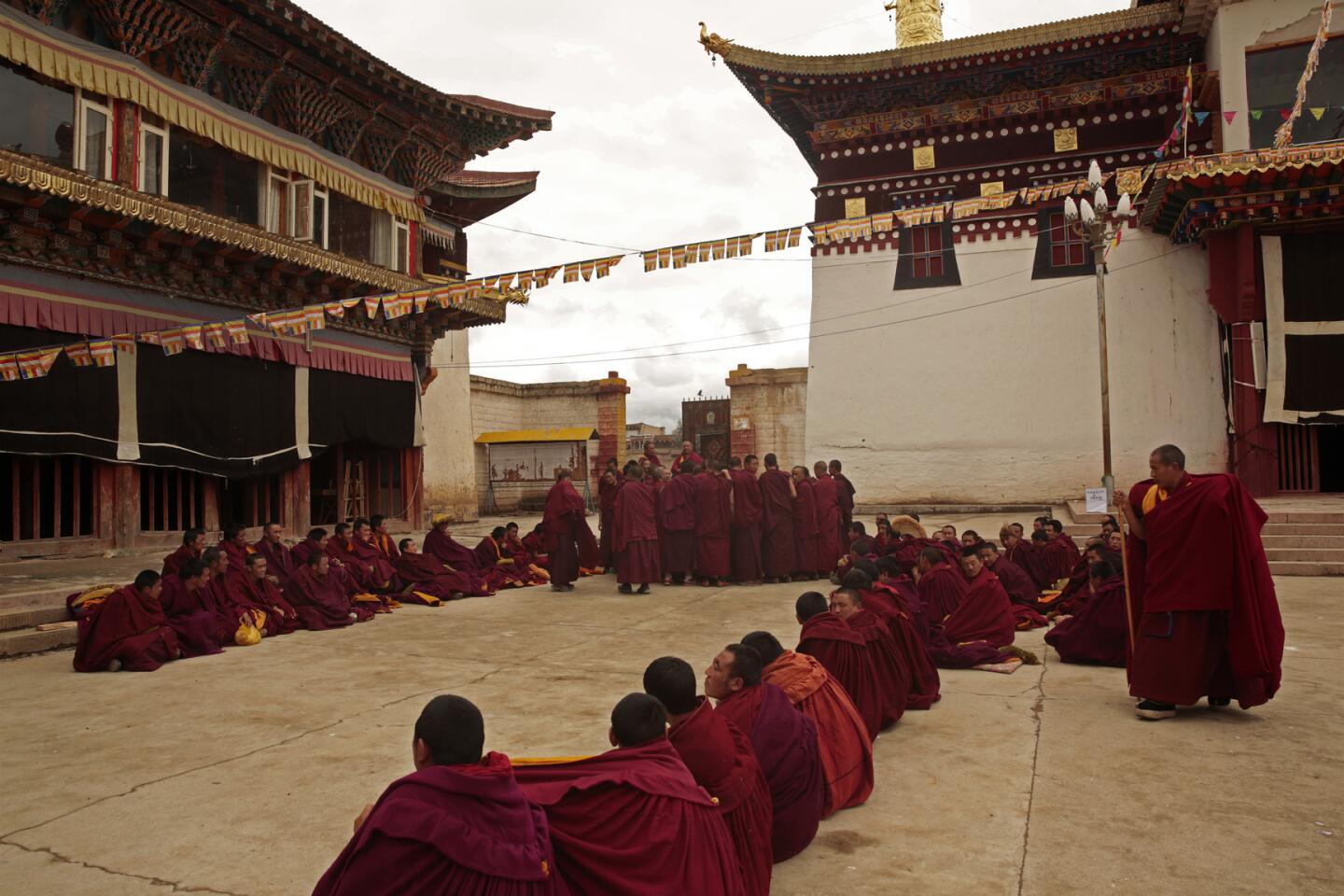

The undercurrent of unhappiness with Chinese rule exploded on a Sunday morning in March 2008, in the courtyard in front of the Kirti Monastery, where monks were conducting prayers for the upcoming Tibetan New Year.

In the middle of the chants, one monk started speaking about independence. People shouted along, raising their fists in the air, ignoring the entreaties of older monks. It degenerated into a riot, with Tibetans hurling rocks at the police and trashing Chinese-owned shops, including the fanciest department store, which happened to be owned by a former People’s Liberation Army soldier.

Chinese troops used tear gas and smoke bombs, then switched to live ammunition.

At least 18 Tibetans were killed, including a 16-year-old schoolgirl. It was a galvanizing moment for a small town in which almost everybody knew somebody who died.

Dhukar, now 18, a slip of a teenager with a ponytail and chipped nail polish, was a student at a Chinese-language public school and so pro-Chinese that she could have been a poster child for the Communist Party. She spoke Chinese better than Tibetan, rarely wore traditional clothing and loved the war movies on television with the matinee idols playing Chinese soldiers.

Watching the riot from a second-floor tea shop overlooking the main street, Dhukar was horrified to see Tibetans throwing rocks at the soldiers. “I thought: ‘These soldiers are here to protect us,’” she said.

But she found out later that three young people she knew had been shot, two fatally. That night the Chinese television news “talked only about Tibetans throwing rocks, nothing about Tibetans getting shot,” she said. “I knew it was lies and that I couldn’t believe Chinese television again.”

Dongtuk was a 14-year-old monk at Kirti at the time. After the protests, the monastery was placed under siege, with barracks built on the grounds. The school he had attended was closed. Police conducted regular inspections, searching for banned photos of the Dalai Lama, the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader. A closed-circuit camera was erected directly outside Dongtuk’s window.

“It was really a period of crisis,” he recalled.

The first self-immolation took place in February 2009. Religious authorities were threatening to prohibit the monastery from observing a scheduled prayer ceremony, especially infuriating one monk in his late 20s who set himself on fire.

That monk, named Tapey, didn’t die, but was left badly disabled and in police custody. There were no more self-immolations in Aba until 2011, when Dongtuk’s friend, Phuntsog, killed himself.

Dongtuk explained why he nearly followed suit.

“I thought somehow if I self-immolated, the news would spread overseas and it would gain support for Tibetans, and in the end it would help people live happy and peaceful lives,’’ he said.

Although he ultimately held back, many others didn’t. Among them were Dongtuk’s half-brother and Phuntsog’s brother, both of whom later burned themselves to death.

The most recent self-immolator in Aba was a 45-year-old barley farmer with seven children. He set himself on fire April 16 in the courtyard of his home so that firefighters would not be able to reach him before he perished.

Many of those who died were the descendants of Tibetans who had fought the Chinese in earlier generations. Phuntsog, 20, was the grandson of a resistance leader who fought the Chinese Communists in the late 1950s.

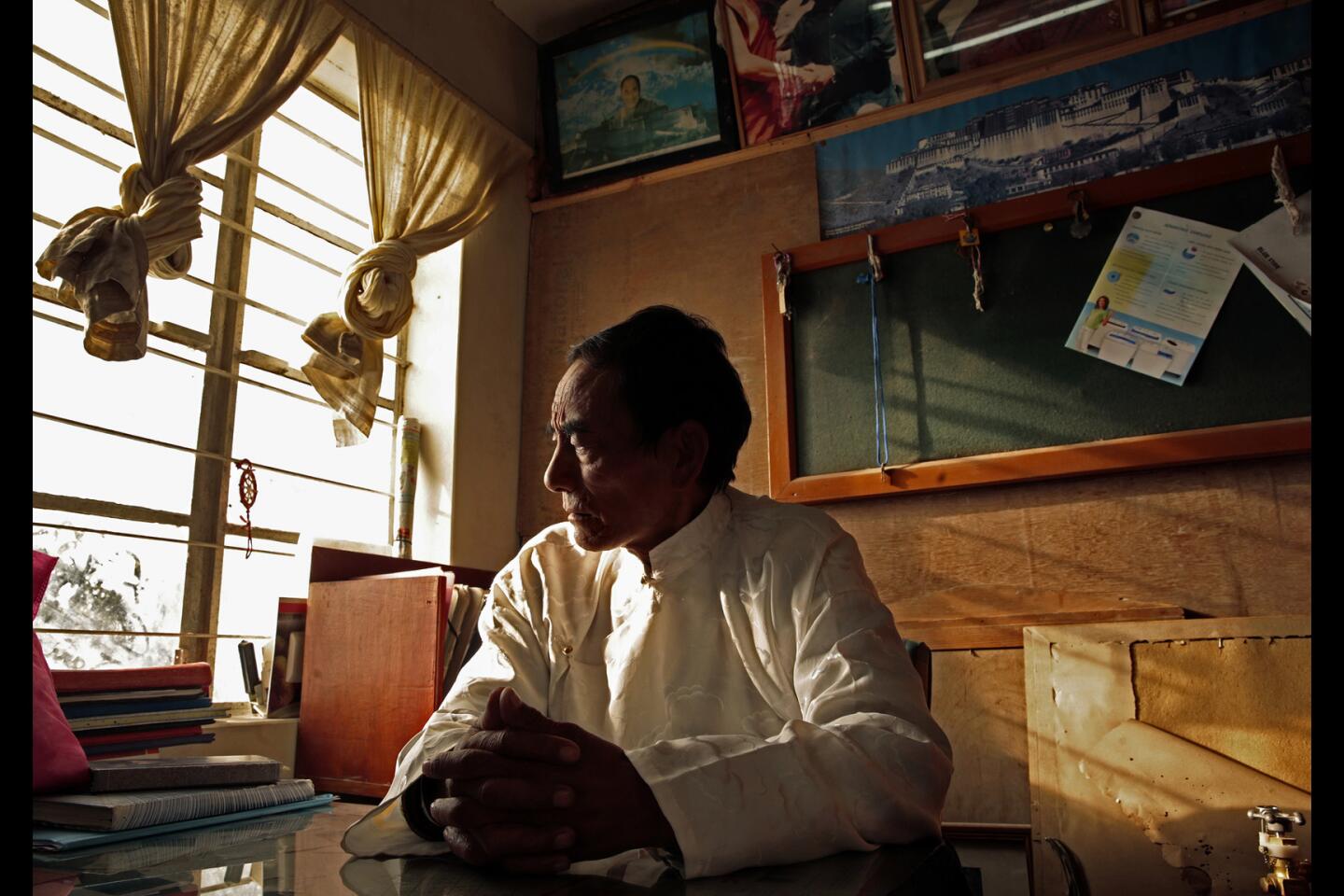

“Aba is a special place. Three generations have suffered from the excesses of the Chinese Communists, and their attitudes have been passed down from generation to generation,’’ said Kirti Rinpoche, the head of the Kirti Monastery, in an interview this year in India, where he lives in exile.

Out of 140 self-immolations in the last several years, more than a third took place in and around Aba. Hundreds of Aba residents have been arrested — and at least a dozen are still in prison — on homicide charges for helping self-immolators. These include shopkeepers who sold gasoline and people who helped with Buddhist funeral rites.

A 29-year-old homemaker, Dolmatso, was arrested in 2013 and held for more than 18 months on charges of being an accessory to murder, according to her brother. She had been on her way to pick up her daughter from school when a man burned himself.

“My sister didn’t know this man,” said Kunchok Gyatso, a Tibetan activist who works with an association of former political prisoners in Dharamsala, India. “Tibetans tried to load his corpse into a truck so that they could do a Buddhist funeral. She was helping.”

One result of the recent turmoil has been growing self-awareness of Tibetan identity. Unable to directly confront the Chinese, Tibetans have begun low-key initiatives to preserve their language, clothing and Buddhist traditions.

On June 21, when the Dalai Lama turned 80 on the Tibetan calendar, Aba residents dressed in Tibetan clothing to show their respect.

Tibetans in Aba are trying to bolster their mother tongue by banishing Chinese from their vocabulary. A computer is now a tsekor instead of a diannao, and a cellphone is a kapor, not a shouji.

“We keep a jar around so that if you say a Chinese word by mistake, you pay a fine,” usually about 15 cents, said a cultural activist in his 30s who asked not to be quoted by name because he feared Chinese authorities. “Then we will take the money in the jar and go out and have a meal together.”

Tibetans say the Chinese government has been paying more attention to the needs of Tibetans since the immolations began. Photos of the Dalai Lama were put back last year inside Kirti Monastery and are gradually making a reappearance on shop walls.

A few weeks ago, the prefecture to which Aba belongs organized a trip for journalists to see government-built housing for Tibetan nomads. Reporters were brought to the spacious home of a former nomad who had been the Communist Party secretary for his village and shown a guesthouse displaying large photographs of Mao and the late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping.

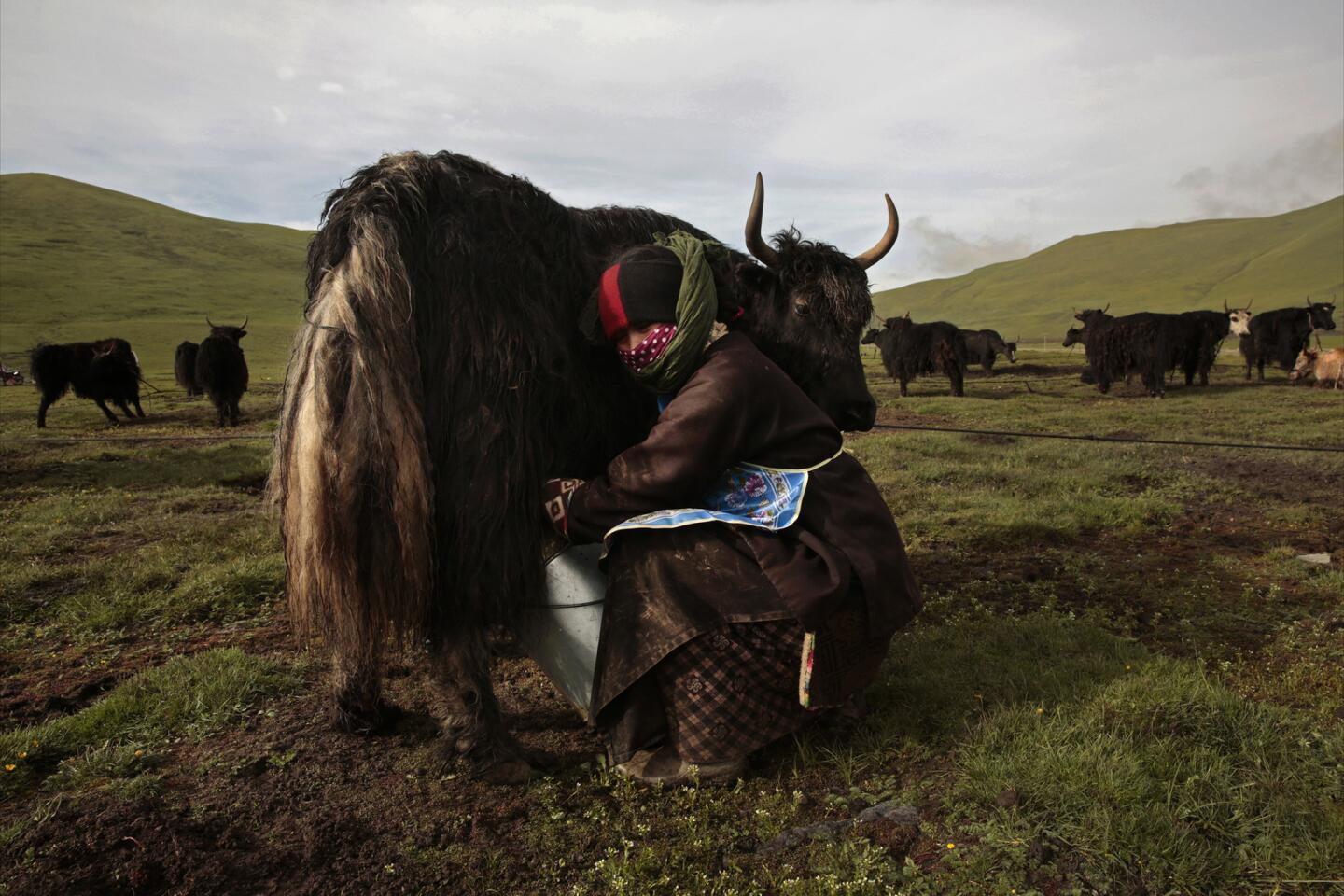

Last summer, many nomads could be seen pitching white waterproof canvas tents distributed free by the local government, replacing the bulkier traditional tents made of black felt. The local government also gave out lumber to build pens for yaks and freed up grant money for Tibetans to make additions to their homes.

A 21-year-old college student, Roumo, visiting her nomadic parents during school break, showed off her brand-new iPhone 5, and a solar panel powering a new flat-screen television.

“Life has changed so much. We have vehicles, phones, television, electricity,” said Roumo.

Said another Tibetan woman, Lhamo, a semi-literate homemaker in her 30s: “I don’t approve of self-immolation, but I have to admit we are getting more from the government. The self-immolators did make sacrifices to improve our lives.”

Still, she said many of her neighbors remain desperately poor.

“In my village, people eat nothing but tsampa,” she said, referring to roasted barley, a Tibetan staple. “They plant barley and before it comes in, they don’t have much to eat.”

And even among those who are doing well, resentments sometimes simmer. Tenzin is a middle-aged businessman who has a considerable real estate portfolio, drives an imported SUV and carries a recent model iPhone.

“I have everything,’’ he said. “Everything but my freedom.”

FULL COVERAGE: Tibet’s Road Ahead

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.