Philippine police killed a mayor and much of his family. Was it a raid gone wrong, or a massacre?

Police raided Ozamiz Mayor Reynaldo Parojinog’s house and killed 16 on the Philippine island Mindanao on July 30. (Aug. 7, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

Reporting from OZAMIZ, Philippines — Mayor Reynaldo Parojinog’s supporters have cleaned up most of the blood, but its smell still lingers, a pungent, metallic odor. His walls and ceiling are riddled with shrapnel. A framed photo of his children hangs on the stairway, shattered and askew.

It happened just after 2 a.m. July 30 as a rare power blackout cloaked the city in darkness.

Police raided Parojinog’s house in central Ozamiz, a city of 140,000 people on the Philippine island Mindanao. For at least 30 minutes, the neighborhood — a warren of low-slung homes beneath a tangle of telephone wires — convulsed with gunshots and explosions. By sunrise, as the chaos subsided, 15 people were dead, including Parojinog, 60; his wife, Susan, 52; his brother; his sister; and several bodyguards.

The police claim they were serving a search warrant for drugs and weapons. Parojinog’s bodyguards attacked, and they returned fire.

The Parojinogs claim the police perpetrated a massacre.

“Everybody’s in shock,” said a close relative who, like many Parojinog supporters interviewed for this story, refused to give her name, citing fears that police would kill them. “All the people here in Ozamiz, they feel sad for him. All of them.”

The incident represents a new stage of President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs, a brutal, often extralegal campaign that has left thousands dead. So far, most victims have been impoverished addicts and low-level runners who turned to drugs — primarily shabu, an inexpensive methamphetamine — to escape the grinding drudgery of urban life.

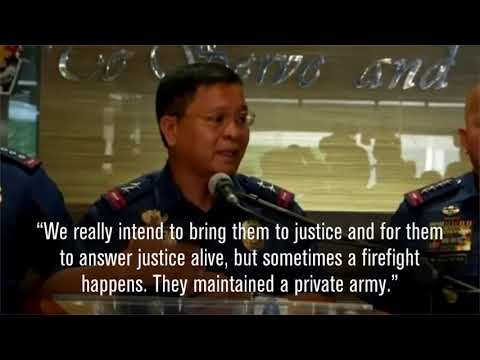

In March, National Police Chief Ronald dela Rosa announced a new phase of the campaign. Police would now target the trade’s enablers — “big-time drug personalities and groups.” Parojinog was on the list.

“The Ozamiz incident is a grim warning that those who persist in the illegal drug trade will only reap what they have sowed,” Dela Rosa told reporters.

On Wednesday, Duterte in Manila stood by the police who conducted the raid. “I will answer for it,” he said. “I will say I ordered it.”

Duterte, after a meeting Monday with Secretary of State Rex Tillerson at a regional conference in Manila, angrily brushed off reporters’ questions about his human rights record.

“Human rights … ,” Duterte said, using an expletive.

“Policemen and soldiers have died on me. The war now in Marawi, what caused it but drugs?” he said, referencing an armed conflict in the country’s south that has killed nearly 700 people. “So human rights, don’t go there.”

Parojinog is not the first mayor to fall victim to the campaign. In August 2016, Duterte publicly linked more than 150 officials and policemen to illegal drugs. In October, police shot and killed Samsudin Dimaukom, a small-town mayor in the south, at a checkpoint. In November, another small-town mayor, Rolando Espinosa of Albuera, Leyte province, was shot dead in a jail cell. Both were on Duterte’s list.

But the killings July 30 — perhaps the bloodiest of the campaign — have gripped the nation, riling senators and attracting wall-to-wall coverage in the local news media.

“This is clearly an indication that the war against illegal drugs is going to continue in earnest,” said Richard Javad Heydarian, author of the forthcoming “Duterte’s Rise.” “I wouldn’t be surprised if the incident in Ozamiz is all about the national police saying, ‘Now we’re moving up the supply chain and targeting the big boys.’”

At least half a dozen senators have publicly questioned the incident. Why did police serve a search warrant at 2 a.m.? If the mayor’s security detail fought back, why were no police seriously injured? Did 15 people really need to die?

Sen. Panfilo Lacson warned that the deaths “create the impression that search warrants are merely being used by the [Philippine National Police] to facilitate extrajudicial killing.” Sen. Leila de Lima, a prominent opposition figure, called the incident a “plain and simple extermination.” At least two senators have called for an investigation.

Jovie Espenido, Ozamiz’s police chief, oversaw the police department in Albuera when that city’s mayor was killed in November. He was transferred to Ozamiz the following month.

“There were reports that Mayor Parojinog was involved in not only drugs, but also had been prosecuted by the government for involvement in robbery,” he said in an interview. “It’s public knowledge in the city that they’re armed.”

Espenido said police arrived at Parojinog’s house after 2 a.m. and quickly encountered gunfire. Two rounds hit a police vehicle, and one grazed an officer’s head. Officers then heard an explosion in the house; when they entered, they found one of Parojinog’s security guards holding the pin of a grenade, his legs blown off at the knees.

Espenido shared photographs of contraband his force had ostensibly confiscated during the raid: so many handguns, shotguns and assault rifles, they couldn’t fit on one table.

Police also arrested Parojinog’s daughter, Vice Mayor Nova Princess Parojinog, and his son, Reynaldo “Dodo” Parojinog Jr.

“We have apprehended here 140 or 150 people [in Ozamiz] for involvement in illegal drugs,” Espenido said. “And we’ve tracked them to the vice mayor.”

On Wednesday afternoon, Parojinog’s friends, family and supporters gathered at his wake at a basketball court near his home. Five open caskets, each containing a heavily made-up Parojinog family member, were ringed with dozens of floral wreaths donated by City Hall employees and local businesses. .

There, two relatives described a very different scene. They were far from the house when the raid occurred, held back by a police cordon. But they said a witness — Parojinog’s brother’s driver — survived, and they recounted his story.

Police roused the Parojinogs, then corralled them in the living room and made them lie on their stomachs, according to the driver. They walked out and threw a grenade into the room. The blast killed Parojinog’s sister Mona, 52, and one other person immediately. Then police returned and shot three survivors: Parojinog, his wife and his brother.

The driver smeared the mayor’s blood on his face and body so police would think he was dead, then crawled from the house once they’d left. The relatives would not give the driver’s name and said he was in hiding.

“Now the family seeks justice, especially for the [mayor’s] sister and the brother. They were innocent and not on the list,” said the other family member. “Why did law enforcement kill them all and not investigate them? We’re asking why. It’s a big question mark.”

On Tuesday, Parojinog’s nephew died in a hospital, bringing the death toll to 16.

Parojinog’s employees accused the police of a coverup. “He had a lot of cameras — six of them,” one said. “Because he knew that something bad would happen to him.” Police confiscated all of them in the raid. When asked why Parojinog was afraid, the employee said, “because he was a politician.”

The Parojinogs have cast a shadow over the region since the 1980s, when the Philippine military helped Reynaldo’s father, Octavio Parojinog, organize a vigilante group to combat the province’s communist guerrillas. The group, Kuratong Baleleng, evolved into a criminal syndicate.

“These people took advantage of the fact that they had weapons, and were backed by the military, to engage in criminal activities,” said Roland Simbulan, a professor at the University of the Philippines and author of “Modern Warlordism in the Philippines.” They sold drugs, kidnapped people for ransom and robbed banks, Simbulan said. They also shared the spoils with their community.

“That’s why, of course, in that province and in the city, you might even say that they’re very popular,” he said. “Whatever they gained materially, they shared, like Robin Hood.”

Reynaldo was elected mayor for five consecutive terms since 2001, and three of his brothers held regional positions of power. His supporters extolled his kindness. “I’d go ask about problems, financial problems,” the former employee said. “He’d give us money or medicine.”

“The whole city loved the mayor very much,” another former employee said. “He was very kind. People are saying that because of what happened, there’s no one we can ask for help.”

He stared at the crater in Parojinog’s floor. “We don’t have a good mayor anymore,” he said.

For more news from Asia, follow @JRKaiman on Twitter

ALSO

‘China has conquered Kenya’: Inside Beijing’s new strategy to win African hearts and minds

Tough new sanctions approved by U.N. could cost North Korea $1 billion in exports annually

Get ready to rumble: Taiwan’s legislative battles feature punching, shoving and tackling

UPDATES:

3:15 p.m.: This article was updated with additional comments by Duterte.

This article was originally published at 3 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.