In Hiroshima, atomic bomb survivors are available to tell their story to anyone who will listen

Reporting from Hiroshima, Japan — Once a month for the past year, 72-year-old Kazuhiko Futagawa has sat at a coffee shop a few blocks from where his father was reduced to ashes when the U.S. dropped the first atomic bomb in the waning days of World War II.

The Social Book Cafe is tucked away on the second floor of a nondescript office and apartment building near downtown. It has just a handful of tables, providing an intimacy that leads to hushed conversations and quiet reflection.

The cafe accepts reservations, but most visitors drop in unannounced. It was an American family that sat down at his table in October, eager for a history lesson.

Judi and Syd Saperstein, born just after World War II, were at the tail end of a visit with their son, stationed at nearby Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni.

The couple had enjoyed learning about Japanese culture over the past few weeks and planned to visit the Peace Memorial Park, dedicated to the legacy of the bombing, later that day. But first, they stopped by the coffee shop for an interaction that would personalize the experience.

For while they had known about the attack on Hiroshima — where an estimated 60,000 to 80,000 people were killed instantly and tens of thousands more died from the effects of radiation — from the time they were in elementary school, Futagawa and his family had actually lived it.

Futagawa is one of the youngest of the hibakusha: survivors of the atomic bomb.

Now, he is one of 18 hibakusha who lead a series of one-on-one talks that have taken place three times monthly since the cafe opened last year. Two of the sessions are held in Japanese and the third in English for the many foreigners who now visit the reconstituted Japanese city.

Futagawa, who still lives in Hiroshima, began his talk with the American baby boomers by detailing the events of that day 73 years ago.

His 13-year-old sister, along with his father, perished immediately, he said, when the Enola Gay dropped the atomic bomb at 8:15 a.m. on Aug. 6, 1945. Both had probably just arrived at work when the uranium bomb known as Little Boy was deployed.

The next day, his mother, two months pregnant, began a frustrating search for her husband and her daughter, the oldest of three. Day after day, she checked the simmering rubble, the riverbanks and a nearby island where thousands of the injured had been taken.

Their bodies were never found. So she did her best to forget.

Eight months later, on April 6, Kazuhiko Futagawa was born.

Judi Saperstein pointed to Syd and said, “September 1946.”

Then to herself:

“February 1947.”

Futagawa’s eyes widened and he smiled.

“Oh really? Same generation.”

The Sapersteins grew up hiding under desks during air raid drills and learning about nuclear weapons testing in Nevada.

“We knew it was serious business,” Judi Saperstein said.

Futagawa, on the other hand, said he wasn’t told his family’s story about the bomb or the fate of his father and sister until he was well into adulthood.

Futagawa is classified as a survivor because he was in utero at the time of the blast. His mother, who died in 2000, never shared the story of that day with him, he said. That task eventually fell to his aunt and cousin when he was in his 30s.

Just four years ago, his remaining sister was going through a chest of drawers that had belonged to their mother. Deep in the back of one of the drawers was a green blouse wrapped in rice paper.

When Futagawa saw it, he felt pain and regret.

It was a school uniform identical to the one his deceased sister would have been wearing when she went to work in a factory the morning of the bombing.

“Why would my mother keep this uniform?” he wondered at the time. “Why didn’t she talk about anything?”

Now he thinks he understands.

“This tiny blouse shows everything about the bombing that caused unspeakable human suffering,” Futagawa told his visitors as he showed them a picture of it.

The shirt was all his mother had left of her daughter. She couldn’t talk about that day because her grief was too deep. So she hid it away.

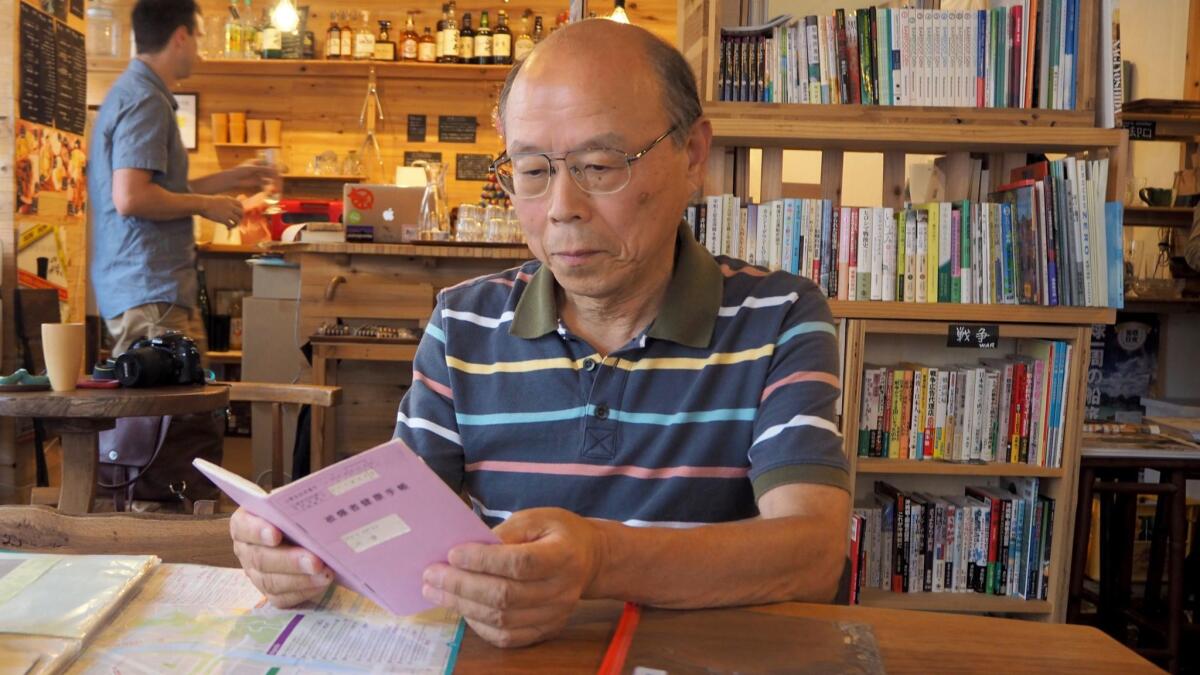

Futagawa pulled out a purple booklet and passed it around the table. It was a medical book that entitled hibakusha to receive free healthcare. Futagawa applied for it when he was 36; his mother never had.

He explained that he found out later that she didn’t want her children to experience prejudice and discrimination as survivors.

That surprised Judi Saperstein.

“They were the ones who were harmed,” she said.

Syd Saperstein didn’t understand either.

“What was the stigma?” he asked.

Radiation exposure. Plus, a society that wanted to forget what happened on both sides of the war.

To explain further, Futagawa told a story about how NHK, Japan’s public broadcasting organization, wanted to interview him several years ago. His wife advised against it because she feared their grandsons would see it and know he was a hibakusha.

Recently, though, as Futagawa has seen survivors succumb to old age and illnesses stemming from radiation exposure, he worries the narrative of that day will die with them.

“We mustn’t let the cruel lessons of the A-bomb and war fade with the passage of time,” he said.

And so once a month, he sits at the coffee shop and waits for anyone who will listen to his story.

Gahan is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.