U.S. scientists have been quietly working in Hiroshima for decades

Reporting from Hiroshima, Japan — Ikuko Murai remembers when the American Jeeps would come after school to take her and other young survivors to a lab at the top of a hill. This was the 1950s, just a few years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

“They examined my head, and measured my height,” she said in an interview this week. “At that time, Japan still had nothing, so I still remember the candy they gave us, with Disney characters on the wrappers.”

Murai had been an infant when the Enola Gay flew over Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, unleashing the first nuclear weapon ever dropped in war. Now 71, she spends her days as a volunteer at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, donning a green shirt and explaining how she survived while the blast and radiation effects left 140,000 dead within months.

Such oral histories are a key part of World War II’s legacy. But in the immediate years after the destruction, American scientists knew that the bodies of Murai and other survivors would also have stories to tell about the unprecedented bombing -- and began collecting data on them.

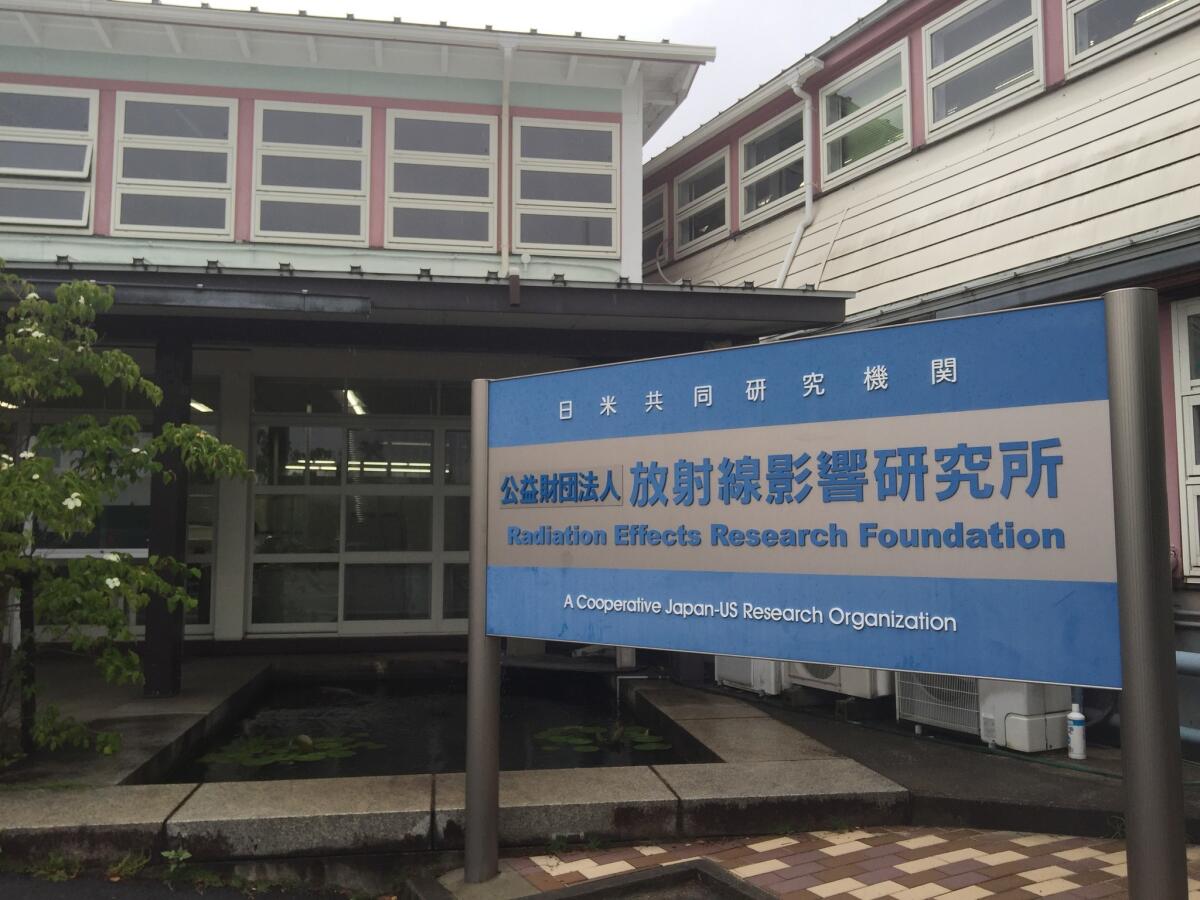

Almost seven decades later, some American scientists -- working side-by-side with scores of Japanese colleagues -- are still up in Hiroshima’s foothills at the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, collecting and analyzing data from hundreds of thousands of A-bomb survivors, their children and control subjects, and publishing studies on their findings.

While largely unheralded outside of scientific circles, and unknown even to many younger Hiroshima residents, the researchers’ joint efforts are a unique example of how the two former adversaries forged a collaboration amid the ashes of hate and war, creating a project to benefit people worldwide.

With funding from the U.S. and Japanese governments, foundation scientists have produced a body of knowledge that has become the basis for radiation-exposure guidelines for X-ray technicians, airline pilots and even nuclear power plant workers around the globe.

RERF studies have elucidated the links between radiation and not just cancer, but also cardiovascular disease and other ailments. And researchers’ expertise has been tapped to deal with emergencies such as the 2011 meltdown at Japan’s Fukushima nuclear power plant.

“This is a treasure trove for the world for research,” said Eric J. Grant, the foundation’s associate chief of research who has spent two decades in Hiroshima. “There are basically no studies that have tracked such a large group for so long.”

Walking into the lobby of the foundation’s Quonset-hut headquarters, opened in 1950, feels more like entering a doctor’s office than a world-class research lab. At the front desk, a smiling woman in a white lab coat offers a hushed “irrashaimase!” welcome to anyone who passes through the door.

For almost 60 years, more than 20,000 atomic bomb survivors have been tracked in the foundation’s Adult Health Study, coming in every two years for physical exams, electrocardiograms, chest X-rays, ultrasounds and biochemical tests.

They are among 120,000 people in the foundation’s Life Span Study, an epidemiological research effort that tracks hospital and death records, aiming to investigate the long-term effects of atomic bomb radiation on cancer and causes of mortality.

Participation rates in the clinical study have hovered between 70% and 80% for decades -- a remarkable feat considering that subjects are not paid for coming back, nor do they receive any direct medical care from the foundation. Treatment is left to doctors at local hospitals.

The continued willingness of survivors to participate is all the more notable given that the foundation’s predecessor organization -- a U.S.-funded entity called the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission -- was initially regarded by many locals with suspicion or even hostility.

Twenty years from now, there will be almost no survivors left. So does that mean no RERF?

— Ohtsura Niwa, chairman of the Radiation Effects Research Foundation

“They would not treat the patients. So the people felt that we were guinea pigs twice -- first as targets of bombing, and secondly as a sample for scientific medial research,” recalled Setsuko Thurlow, who was 13 when Hiroshima was bombed.

“A close friend of mine as a child was taken to ABCC occasionally. In front of the [male] medical staff, she had to undress, totally naked,” said Thurlow, who ended up marrying a Canadian. “She still remembers the sense of shame and embarrassment and talks about it even today.”

That sense of antagonism faded, though, as the U.S. occupation ended, and conditions in Hiroshima improved. In the 1970s, the ABCC was reorganized into a nonprofit foundation, with bi-national oversight committees and funding from the U.S. Department of Energy and Japan’s Ministry of Health.

At its peak, the research center had more than 1,000 employees. Today, it’s down to about 230, and fewer than 5% are Americans, though they hold key positions, including vice chairman and chief of the statistics department, and serve on advisory boards.

While the foundation owes its existence to America’s use of one of the most horrific weapons ever devised, current employees say they don’t feel burdened by historical tension on the job.

The march of time, the overarching U.S.-Japan alliance and cultural understanding built up over the decades -- not to mention the camaraderie forged by doing groundbreaking science together -- has bridged whatever chasms initially existed.

Kazunori Kodama, the foundation’s chief scientist, had a cousin who perished in the bombing. Still, he said, “I never blamed the U.S. for my cousin’s death.”

Such a perspective is not uncommon among Hiroshima’s Japanese residents, though it often catches Americans off guard at first.

“I was surprised when I came here and found there was no palpable animosity related to the bombings in this organization,” said Harry M. Cullings, a Pennsylvania native who first arrived in the late 1990s and is now the head of the statistics department.

“There are cultural differences -- Americans are more brash and opinionated. ... They are less reserved about being intellectually competitive in ways that might offend their colleagues. They are willing to get into big arguments,” he said. “In the Japanese culture, people are more reserved and respectful to each other but also less willing to debate -- but that’s about it.”

On Friday, President Obama will visit the Hiroshima Peace Memorial to lay a wreath and deliver remarks about the perils of nuclear arms. Residents of this port of 1.1 million are largely welcoming him with open arms.

Many Hiroshima natives see the first visit by a sitting American president to their forever-scarred city as not only a fresh step for global disarmament efforts, but also a momentous, if long-overdue, move to cement the reconciliation between two mortal-enemies-turned-allies.

But Obama has no plans to visit the foundation, and scientists here acknowledge that doing so might be tough for the president. Already, his trip is under fire by some Americans who see it as tantamount to an apology (although White House officials insist he won’t use that word).

“I don’t think the political optics are favorable to his coming” to the foundation, said Cullings.

Still, other foundation staffers say Obama’s trip could at least re-focus politicians’ attention on issues of nuclear research and safety -- and underscore the importance of continued funding for the organization. “Obama’s visit [to Hiroshima] certainly won’t hurt,” said Douglas Solvie, the foundation’s chief of secretariat.

While 95% of the foundation’s funding still comes from the Japanese and U.S. governments, its leaders have acknowledged they need to diversify their sources of support by competing for grants and soliciting donations.

Part of ensuring the foundation’s viability also entails articulating a vision for the organization after the last A-bomb survivors pass away. Although there were still more than 187,000 survivors alive last year, according to a Japanese government census, the youngest are now in their seventies, like Murai.

“Twenty years from now, there will be almost no survivors left. So does that mean no RERF?” asked Ohtsura Niwa, a Stanford-trained PhD who took over as chairman last year. “No. We intend to keep on going, to do something for the next generation.”

The foundation plans to keep studying the children of A-bomb victims to determine whether they have higher rates of cancer or other ailments that could be related to their parents’ exposure. So far, there have been no discernable effects, but this cohort is now moving into the age range where cancer and other disease become more prevalent, so researchers are keen to track them in the coming decades.

Beyond that, as new technology is developed, researchers hope to be able to apply it to their trove of biological samples. Stored in more than 70 freezers at -112 degrees Fahrenheit, at least 900,000 samples of blood, urine and other material from tens of thousands of survivors of the blast and their children have been collected at the foundation over the decades.

Improved technology, for example, might finally allow scientists to pinpoint whether there are unique radiation-induced changes at the DNA level that cause cancer. Currently, for example, scientists can say that out of 100 cases of a certain type of cancer among A-bomb survivors, 10 are induced by radiation, Kodama said.

“But there is no way to distinguish clinically which one is which,” he said. “If we can identify a radiation-specific change at the DNA level… we can use that for very early detection of radiation-induced cancer. This is one of the dreams.”

The foundation is also looking to study new populations exposed to radiation -- including the 20,000 people who worked on remediation efforts at the Fukushima nuclear plant in the wake of its 2011 meltdown. Right now, plans call for them to be tracked, like the A-bomb survivors, for the rest of their lives. “This is a new area for us,” said Kodama.

The foundation’s extensive biosamples could also be a gold mine for researchers looking into questions of aging and disease that have nothing to do with radiation.

“Other questions can be asked of this cohort beyond just the scope that RERF has created,” said Grant. “There’s a very rich future for research here, not just in terms of radiation effects, but also in terms of aging in general. We can see our role expanding.”

Follow @JulieMakLAT on Twitter for news from Asia.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.