After a chilling sex abuse scandal, many Chinese seek a new way to protect their children: sex education

Reporting from BEIJING — Fifty elementary school students crammed into a rickety classroom at Tongxin Experimental, a school for children of migrant workers in suburban Beijing. Most days, they study math, science, history and other government-mandated subjects.

But on Fridays, they learn about sex. Today’s lesson: how to prevent sexual assault.

“And if your internet friend asks to meet you alone in person, what do you say?” asked the teacher, Li Xueyan, a pharmaceutical industry representative in her early 30s. A part-time teacher, Li volunteers on Fridays for Xixi Garden, a Beijing-based non-governmental organization that teaches sex education in Chinese lower-income schools.

“No!” the students yelled in unison.

Last month, China was rocked by multiple kindergarten abuse scandals, including a particularly harrowing one at Beijing’s Red Yellow Blue Kindergarten. The story’s details, involving sleeping pills and suspicious health check-ups, triggered a rare, national outpouring of public rage. Many Chinese wondered how the abuse could be prevented.

After an official investigation concluded that no sexual abuse had occurred, parents appear to be taking matters into their own hands. Sex education is witnessing a wave of renewed interest. Sexual health textbooks are flying off shelves. Parents have flooded online courses on how to speak with children about sex. In a society with limited trust in public institutions, parents appear to be making a simple calculus: If you can’t eliminate sexual abuse, better to avoid it.

Many parents want us to scare children, to emphasize how terrible sex is, how dangerous our society is.

— Han Xuemei, the founder of Xixi Garden

Han Xuemei, the founder of Xixi Garden, oversees an organization operating in dozens of Beijing-area schools, administering sex education to over 9,000 Beijing elementary school students, mostly in poorer areas. After last month’s kindergarten scandals broke, Han said, schools began contacting her to set up programs.

“After Red Yellow Blue, people started paying much greater attention to us,” she said. “Several kindergartens asked us to help train their teachers.”

Owing partly to long-held cultural taboos around sex and reproduction, China has no nationwide sexual education curriculum. As a result, sex education varies widely from school to school, with many students receiving no education at all. In many areas, especially in poorer regions or outside major cities, programs such as Xixi Garden provide the only sex education students will ever receive.

“Growing up, I didn’t have the slightest idea what sex really meant,” said Liu Yang, 33, a private school teacher in Beijing. “I learned about it from the movies.”

The Chinese government has made tentative steps to improve sexual education. In 2008, the Ministry of Education issued a set of guidelines on “Sexual Health Education,” stipulating that first- and second-graders should learn about pregnancy and “where babies come from.” In 2011, the State Council, China’s Cabinet, issued the “Outline of Chinese Child Development 2011-2020,” instructing schools to include lessons on sex and reproduction in the compulsory curriculum.

Yet experts say many schools have yet to make serious headway into integrating sex into the curriculum.

“There are some NGOs operating, some teachers who are interested in talking about it. But they are really very limited in scope and scale,” said Lily Liu, country director of Marie Stopes International China, which provides sexual and reproductive health services and education.

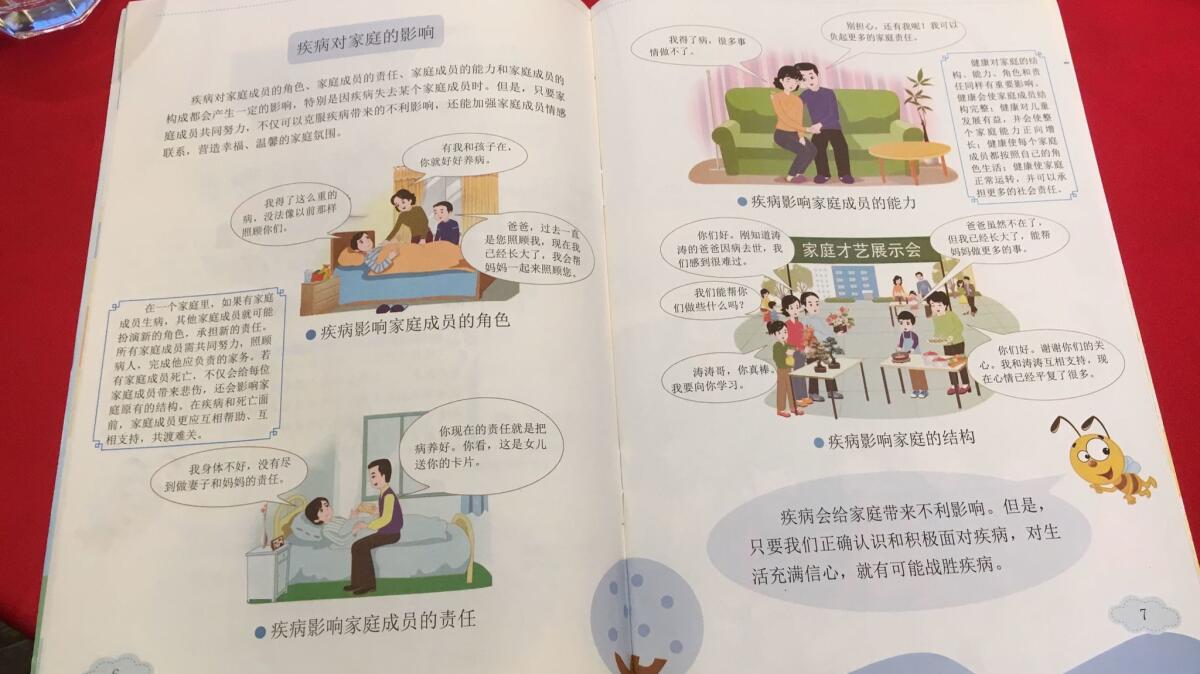

Parents have been a major source of resistance. In March this year, a new Chinese sex education textbook, “Treasure Your Life,” attracted controversy from parents for its frank discussion of male and female sex organs. Its cartoon drawings of an adult couple having sex circulated widely on the internet. In a country that views itself as prizing modesty, many viewed the book as uncouth or embarrassing. Others worried the book might lead children astray.

”Many parents don’t trust their own children,” Han said. “They think that if you teach the kids about sex, they’ll go try it out. They worry it’ll accelerate their sexual development.”

In response to the controversy, the book’s publishers emphasized its role in preventing assault. In a section titled “Why did we do this?” they cited statistics on child sexual assaults, broken down by the age of the victim. Understanding sexual organs, the authors wrote, was one way of preventing abuse.

“We hope this textbook will enable children to … respect themselves and others, recognize dangers, and use appropriate measures to protect themselves.”

Parents have responded. Last month, “Learning to Protect Yourself,” subtitled “Teaching Children How to Avoid Sexual Abuse,” shot to the top-10 bestseller list on Dangdang.com, a Chinese seller of children’s books. It remained there for three weeks.

“After the Red Yellow Blue incident, I rushed to buy my child a book on sex education,” said Weng Limin, 45, a mother in Shanghai. “As they say: ‘You may worry your child is too young for sex education, but a criminal won’t have the same compunction.’”

Chinese state media appear to have gotten behind the movement. In late November, the China Daily published an article titled, “Sex Education Needed in All Schools, Experts Say.” A few days later, the state-owned Global Times ran a story titled, “Sex Education Gains Recognition Among Chinese Parents.”

“Teaching kids about sex, which has traditionally been a taboo and embarrassing topic for many parents in China, is now coming out of the closet,” read the Global Times story.

For Han, renewed attention to sex is a mixed blessing. She welcomes greater interest in sex education but also fears it becoming synonymous with abuse prevention. For years, Xixi Garden has tried to balance sexual assault prevention with attentiveness to all aspects of sexual life, including its potential to nourish healthy relationships.

“Many parents want us to scare children, to emphasize how terrible sex is, how dangerous our society is,” Han said. “But if we use scare tactics, that could affect them later in life. One day they’ll want to get married, to feel love. If we plant the idea that sex is hideous and ugly, how will they face their future marriage, their future partner?”

Yet as repeated sex scandals convulse Chinese society, a focus on abuse is hard to avoid. Regardless of whether perpetrators are brought to justice or the system is reformed, mistrust toward public institutions runs deep. Parents take what steps they can to protect their child from harm.

“You acted very bravely, Uncle Wang shouldn’t have tried to touch you,” a mother tells her daughter in a lesson from Xixi Garden’s textbook, cradling the child’s arm in her hand. “From now on, keep a little farther away from him.”

DeButts is a special correspondent

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.