China proposes to scrap presidential term limit, clearing way for Xi Jinping to stay in power

Reporting from BEIJING — China’s Communist Party plans to eliminate presidential term limits, paving the way for Xi Jinping to stay in office and solidify control over the world’s most populous country.

Senior officials proposed removing from the constitution language that permits the president and vice president to serve “no more than two consecutive terms,” the official New China News Agency announced Sunday.

Xi began his presidency in 2013 and is required to step down after two five-year terms. The proposed change — a spectacular shift from his recent predecessors — could make him the longest-running Chinese leader in decades.

The proposed change brushes aside the collective leadership strategy created after the protracted reign of Mao Tse-tung, the country’s volatile founder, intended to ward against unchecked power.

“This is extraordinary because it represents a real clear and fundamental break with the four-decade-long process of trying to normalize Chinese politics after the chaos of the Cultural Revolution and the Mao era,” said Jude Blanchette, a researcher at the Conference Board in Beijing, who is writing a book about Mao’s legacy. “It puts to rest any doubt that Xi designs to stay in office much longer than we originally thought.”

The news comes a day before the Communist Party’s Central Committee, which includes some 200 high-ranking party officials, is expected to meet in Beijing to weigh major personnel decisions. The committee approved the amendment last month, according to state media, but only released it on Sunday.

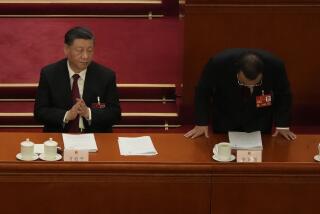

A full party-run legislature will convene in early March to vote on amendments, a largely rubber-stamp affair with choreographed clapping and long speeches. The crucial decisions will already have been determined.

“We are now dealing with a situation where the second-largest economy in the world, and arguably, the other super power, is careening pretty rapidly to de-institutionalization of the highest offices in the land,” Blanchette said. “This move makes the black box of Chinese politics even more opaque.”

Such an amendment seemed almost inconceivable when the party initially elevated a reserved, adequate bureaucrat to the presidency because leaders thought Xi was someone who could be controlled. Since then, the 64-year-old Xi has rooted out dissent — from human rights lawyers to political rivals — and consolidated power to a degree unseen since Mao.

The news wasn’t a complete surprise. Xi declined to name an heir at a twice-a-decade party congress in October, breaking with precedent and leading analysts to speculate that he might seek to extend his tenure.

“This is a very dangerous proposition,” said Willy Lam, an expert on elite politics at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “We now have the theoretical and constitutional underpinning for an emperor for life.”

Only his presidential title has carried formal term limits; Xi also serves as general secretary of the Communist Party and commander in chief of the military, even more substantial roles. Jiang Zemin, who stepped down as president in 2003 after two terms, continued to wield power as leader of the country’s military. Hu Jintao, Xi’s immediate predecessor, yielded complete control when his term ended.

The Global Times, a party newspaper, portrayed the change as a means to ensure stability while China achieves Xi’s vision of a modern, resurgent country.

China and the party “need a strong, stable and consistent leadership,” said Su Wei, professor at the Party School of the Chongqing municipal committee, according to the paper. The shift “is serving the most important and fundamental national interest and the party’s historic mission.”

In another sign of Xi’s influence, officials suggested adding to the constitution his main themes — “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.”

Xi’s rise often draws comparisons to Russian President Vladimir Putin, an authoritarian-style leader who also has amassed remarkable power. But Putin didn’t change the constitution. Instead, he helped install an ally as president for a term and took on the role of prime minister. He returned to the presidency in 2012.

“Putin, at least, was willing to serve some rules,” Lam said. With Xi, “what he says is the rule.”

Meyers is a special correspondent.

Twitter: @jessicameyers

ALSO

China unveils new leadership with no clear successor to Xi Jinping

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.