Even in fast-changing India, kushti wrestling is a wellspring of power, pride and identity

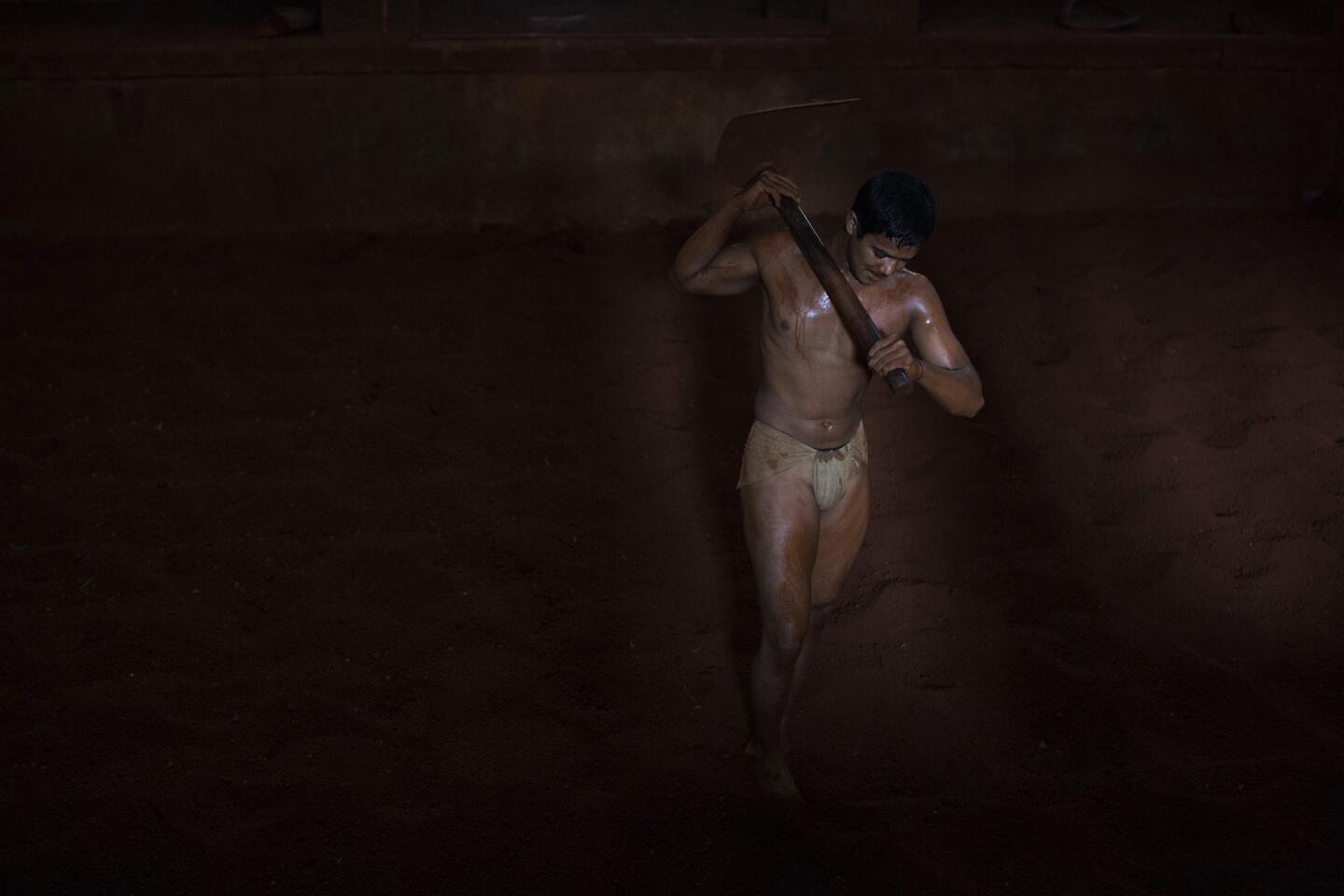

A kushti practioner prepares the floor, which is made from clay -- a mixture of dirt, yogurt, clarified butter and turmeric powder.

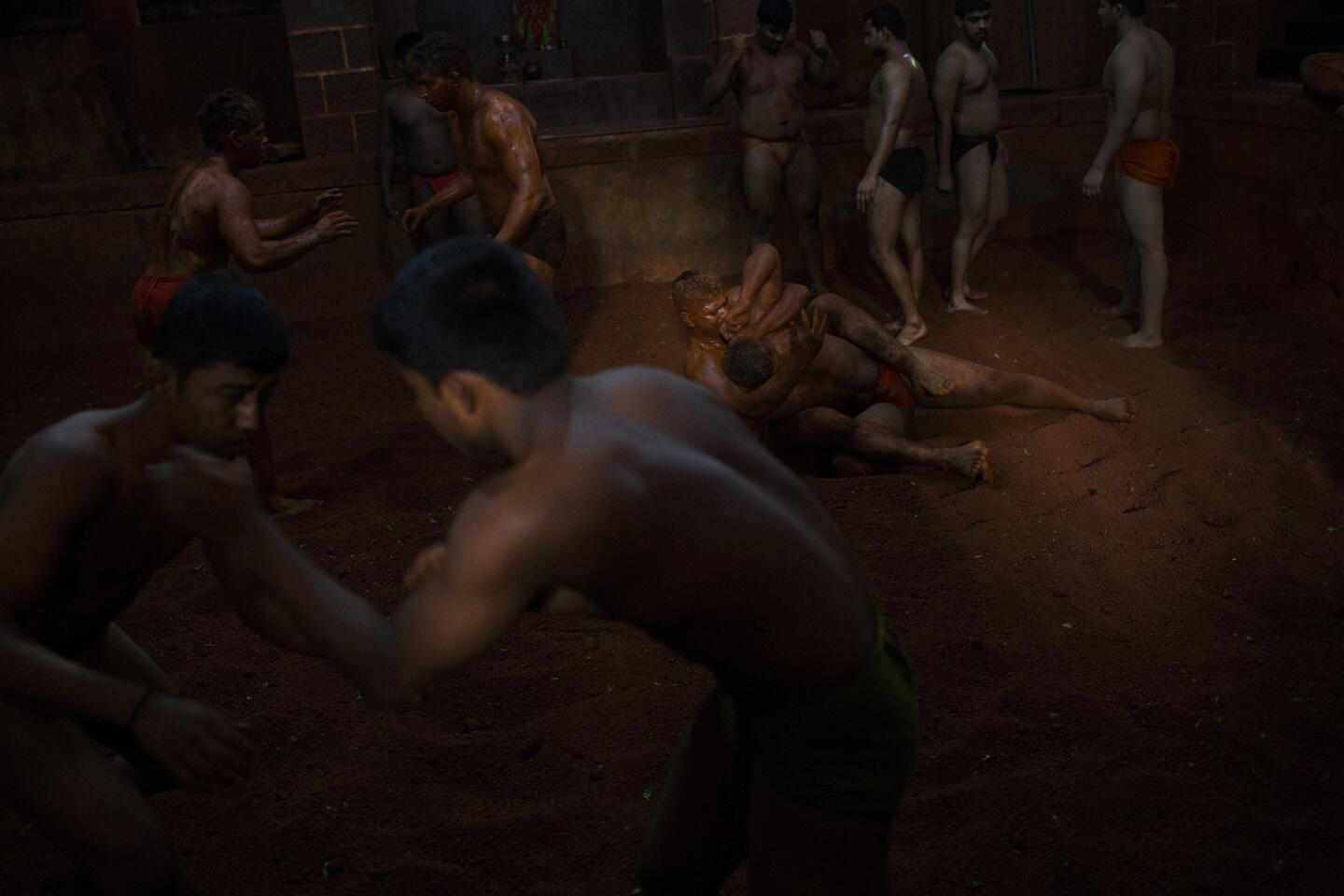

reporting from KOLHAPUR, India — A shaft of light peeks through the doorway of a 100-year-old gym. Two giant men step across a stone floor worn smooth by generations of sweat and dirt, and into a pit of maroon clay that crunches like sand underfoot.

In the near darkness they bow slightly at a shrine to Hanuman, the Hindu monkey god and patron deity of their ancient sport. One man tugs at the loincloth straining against his hips; the other scoops a handful of clay and smears it across the shaggy acreage of his chest.

In an instant, the men lock eyes and begin to wrestle, the way it has been done here for centuries.

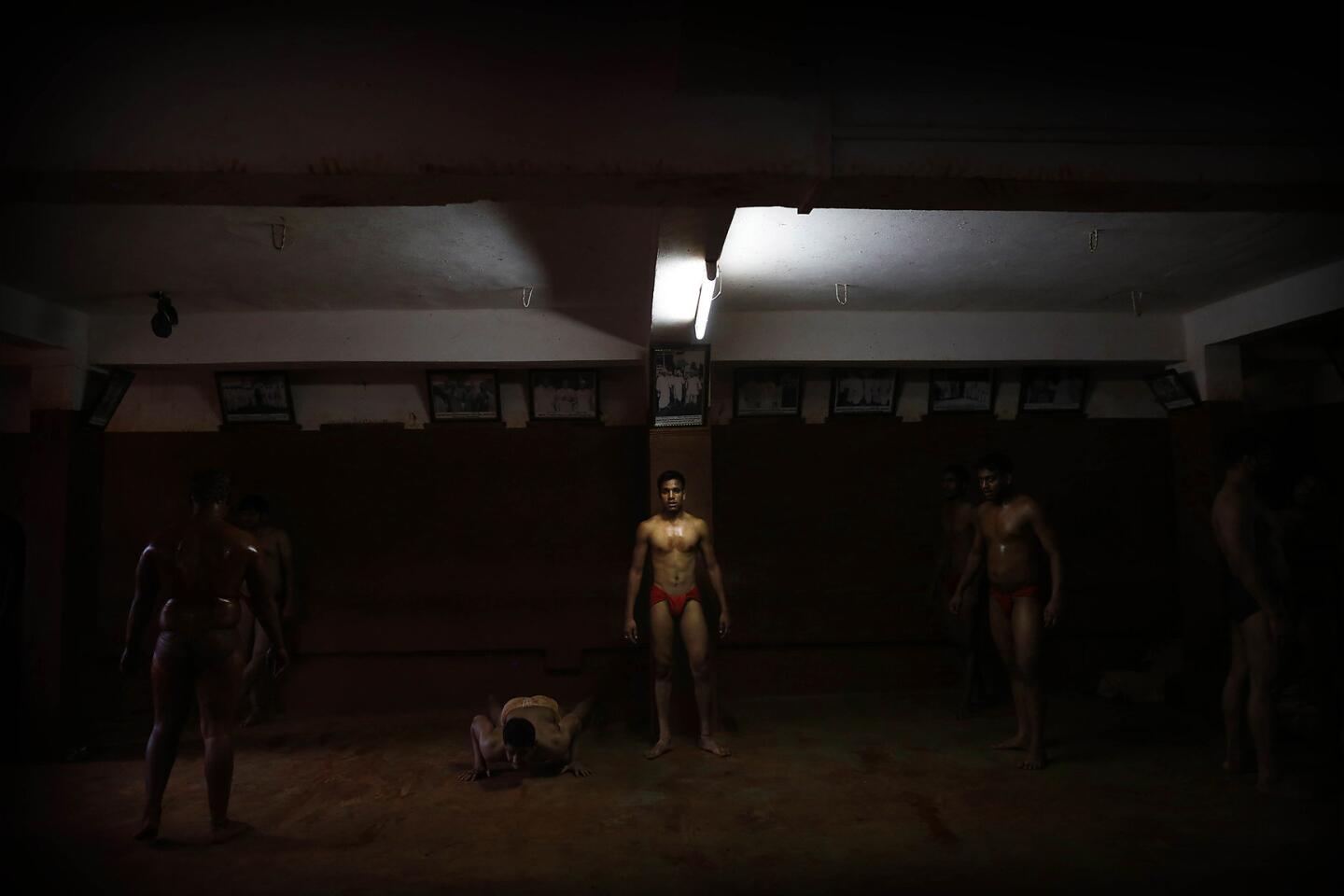

Indian wrestlers training practices. (Shashank Bengali / Los Angeles Times)

The hairier man grabs the flank of his opponent, who steps back for a moment before lunging forward with his meaty right arm. They grapple this way for several minutes, shadowing one another around the earthen pit, a slow dance in the dim light, until they suddenly stop and clasp hands. The practice session is over.

They are practitioners of kushti, a style of mud-clay wrestling that dates to the time when Mughal emperors held sway over this vast fertile plateau in western India. In Kolhapur, a prosperous agricultural city ringed by sugarcane farms and factories, boys as young as 8 come to train in the clay — a mixture of dirt, yogurt, clarified butter and turmeric powder, turned over with a shovel until it is red and chunky-soft.

The last five generations of my family have all practiced kushti. If I have a son, he will also be a wrestler.

— Nandu Abdar

Even in fast-changing India, the sport remains a wellspring of individual power, family pride and regional identity.

“The last five generations of my family have all practiced kushti,” says Nandu Abdar, a powerful 224-pounder who won a state championship in 2010. “If I have a son, he will also be a wrestler.”

Abdar, 28, is unmarried, like most kushti men. The sport demands single-minded dedication from the wrestlers as well as their families, nearly all of whom are farmers, investing precious hundreds of dollars a month into food and travel costs for their athletes.

Abdar grew up on a farm 20 miles away and arrived as a teenager to live at New Motibagh, one of the handful of storied gyms, known as taleems, that train wrestlers in Kolhapur.

That was 14 years and more than 100 pounds ago. His daily diet is a paleo dream: 200 almonds, seven to 10 eggs, a pound of mutton, several bananas, some green vegetables and a half-pound of clarified butter, or ghee. He washes it all down with four liters of milk, often freshly squeezed from one of the cows tethered by the road, a few steps from the academy doors.

He eschews alcohol and tobacco, in keeping with the near-asceticism expected of a serious kushti wrestler.

Resting after a morning jog through narrow streets, Abdar squats on a square wooden trunk in a long room above the wrestling pit. He massages his ears, both of which have been mashed in bouts.

On the bare floor next to him, another wrestler applies traditional ayurvedic oils to his knee, along with turmeric powder, renowned for its healing properties. The soothing compounds are often mixed into the clay, which wrestlers rub on their bodies before and after matches.

The smell of onions and ginger floats from a dorm room below, where a wrestler is preparing lunch over a camper-style gas stove. Younger boys have gone to school.

A few hours later, when the midday sun has released its grip, the stone courtyard of the taleem is filled with wrestlers beginning their second daily workout — a few hundred push-ups followed by a withering circuit of calisthenics, gymnastics, weights, rope-climbing, fireman’s carries and grappling.

Accommodation at the private taleems costs just a couple of dollars per wrestler, and the amenities are correspondingly spare. The men shop for their groceries and cook their own meals. Even the youngest boys look after themselves, though older teenage wrestlers sometimes take them under their wing.

There is no hot water. Bracing, open-air showers double as laundry time, with wrestlers scrubbing T-shirts and skimpy orange loincloths over their knees as they bathe. There is no television at New Motibagh; a few of the older wrestlers own smartphones and occasionally play Hindi songs, at a low volume, on tinny speakers.

At night, the roughly 80 wrestlers sleep by the dozens in spare dormitory rooms, unfurling layers of thin woven mats, the bigger men lying ramrod-straight atop the narrow cloth. The stone floors underneath are hard and cold. Oversleeping is rare, and not encouraged.

Across town, at the 125-year-old Jai Bhavani Shahupuri taleem, a dark welt on the back of 18-year-old Laxman Jadhav, one of the city’s most promising young wrestlers, testifies to the exacting standards of Kolhapur’s coaches.

“He got smacked for being lazy,” another boy explains.

Jadhav smiles but doesn’t look up. He is bent over an earthen pot in a corner, using a long wooden stick to pummel almonds, cashews, honey and cardamom seeds into a paste as he prepares a protein shake.

Mixed with milk, it is as dense as sludge — if marginally tastier — but it works. Jadhav has packed on more than 50 pounds of muscle since his father sent him here five years ago.

“When I go home and my family sees what I look like, they’re happy,” he says. He is ostensibly referring here to his chiseled midsection and not his cauliflower ears, warped and swollen from repeated blows and made even more prominent by his buzz cut, which gives him the appearance of an intimidating monk.

Jadhav’s native farming region of Marathwada, several hours by road from Kolhapur, is mired in a three-year drought that has driven hundreds of farmers to commit suicide. His family has slashed the $150 they used to send every month for food, forcing him to dip into his earnings from local competitions to cover his expenses.

Districts across southern Maharashtra state hold tournaments whose top prizes range from a few hundred dollars in the lower weight classes to nearly $1,500 for heavyweights — more than the average Indian farm household earns in a year — although the agrarian crisis has reduced those purses too. (At some smaller meets, the winner could receive a tractor.)

Politicians also host competitions on their birthdays and other special occasions, continuing a long tradition of official patronage for kushti.

The Mughals who conquered this part of India in the 16th century and the Maratha warrior-princes who supplanted them each promoted kushti, which blended a form of ancient Indian mud-fighting with Persian martial arts. The sport’s golden age in Kolhapur began in the late 19th century when Shahu Maharaj, ruler of what was then a princely state, held contests and invited competitors from across British India.

Most of the taleems of Kolhapur were constructed in that era, their low, crumbling brick facades now obscured by cellphone shops and multistory apartments. Lately, traditional kushti is being eclipsed, too, by the international form of competitive wrestling, which takes place on a mat instead of dirt.

The Indian government has tried to de-emphasize kushti in favor of mat wrestling, hoping to improve the country’s futility at the Olympics. The effort gained a boost when Sushil Kumar, a former kushti star from northern India, medaled at the last two Summer Games.

Two years ago, the Shahupuri taleem invested more than $7,000 — nearly all of it donated -- to install a mat on the second story of the gym, above the clay pit. Three times a week, the kushti wrestlers work out on the padded yellow surface, grunting like hogs, as Ashok Nagrale, the taleem’s 55-year-old head coach, watches from the corner in his undershirt and barks out the names of anyone who’s lolling.

“In mat wrestling, the matches are quicker, maybe 1 to 2 minutes — it requires more speed and core strength,” Nagrale, a heavyweight kushti standout in the 1980s, says afterward, sitting in the courtyard below a portrait of Hanuman.

“Traditional kushti is more about brute force and stamina. The matches can go on for 25 minutes.”

The mat holds the prospect of international success, but most men at the taleems prefer kushti because opponents move more slowly in the clay. The local tournaments that bring prestige to a Kolhapuri pehelwan, or wrestler, are nearly all contested on clay.

The average competitor here does not dream of the Olympics, or even of a state title. He hopes he will do well enough to earn a government job with the police or railways, which reserve slots for successful wrestlers — a sinecure better than uncertain farm life.

Perhaps most of all, he aspires to the glory that comes from being a big man in a small place.

“My family is proud of me,” says 12-year-old Sridhar Godse, one of the youngest boys at the New Motibagh taleem. “The villagers give me respect when I go home. They treat me like a special child. A pehelwan child.”

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

MORE WORLD COVERAGE

Venezuelans are fed up. Here’s why

A ‘global terrorist’ comes in from the cold: Afghan warlord was ally of CIA, then Osama bin Laden

Some debt collectors in Russia will call borrowers at all hours, and then it can get violent

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.