As China and India tussle in South Asia, a pristine mountain kingdom is caught in the middle

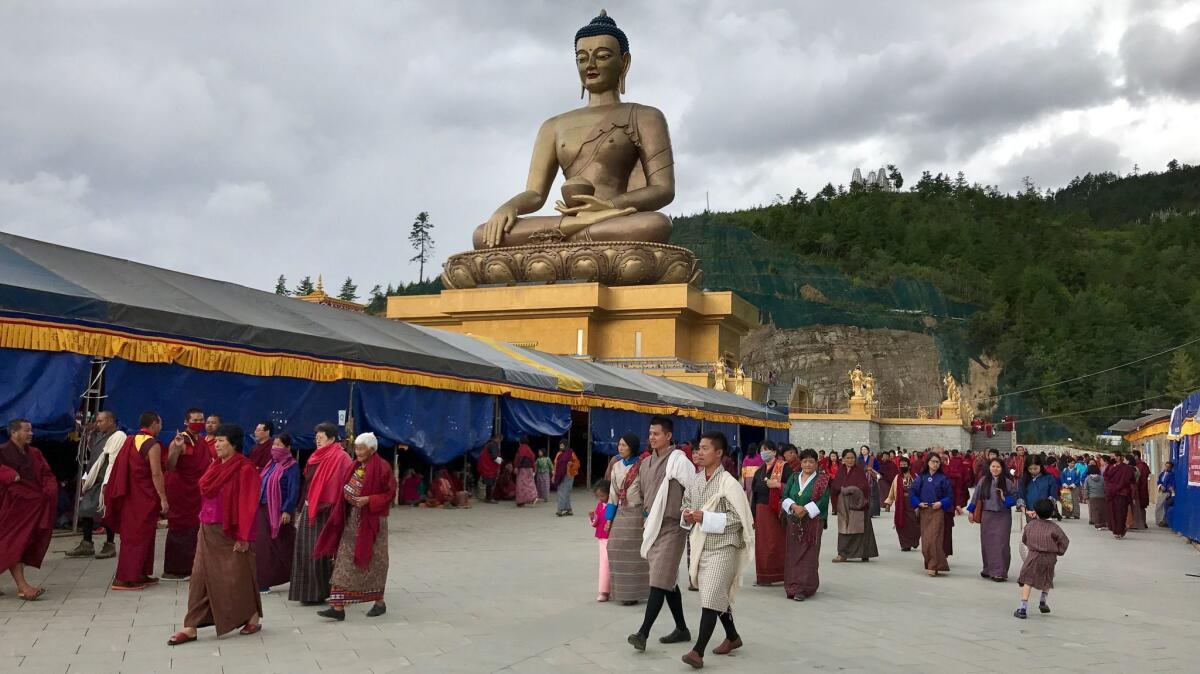

Reporting from Thimphu, Bhutan — Tucked like a jewel into the mighty Himalayas, the mountain kingdom of Bhutan has rarely commanded the world’s gaze, its hillside monasteries and emerald valleys long known only to select travelers seeking adventure or enlightenment.

But for two months, this quiet Buddhist monarchy found itself at the center of a bitter military standoff involving the world’s two most populous countries, each jockeying for primacy in South Asia.

Tensions eased Monday when the rivals, China and India, announced that they had agreed to withdraw their troops from a remote, 10,000-foot plateau near where their borders intersect with Bhutan’s. That ended an impasse that began in June when India sent hundreds of soldiers to block Chinese construction workers and border guards from extending a road running south across the plateau from Tibet.

Both Bhutan and China claim the plateau, and India, Bhutan’s closest ally, said it acted to protect Bhutanese interests. The disputed tundra is populated mainly by yaks, and is frozen most of the year, but has come to hold immense geopolitical value.

China, under President Xi Jinping, has challenged India’s position as the hegemon in South Asia by deepening its partnership with Pakistan — India’s blood rival — and wooing Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and the Maldives with lucrative trade deals and infrastructure loans.

As much as I want to love India, they are slowly driving the Bhutanese toward China.

— Yeshey Dorji, Bhutanese commentator

Bhutan is the only country in the region that remains outside China’s orbit and firmly tethered to India. It has spurned China’s requests to establish formal diplomatic relations, and India has rewarded its loyalty with billions of dollars in investment that has helped bring the landlocked kingdom of 800,000 people into the modern age.

But in the wake of the Indo-Chinese military confrontation — 55 years after the two countries fought a brief war that began with a border dispute — many Bhutanese worry that their country is becoming trapped between its longtime patron and an aggressive new suitor, opening up fissures in a placid society whose guiding principle is the pursuit of “gross national happiness.”

“Nobody wants to be in a situation where two giants are fighting and you are getting squeezed in between,” said Sangpa Tamang, a Bhutanese civil engineer who writes a blog on current affairs.

Geographically isolated, with a small population and few resources, Bhutan might not exist today as an independent state without India, its southern neighbor with a population and economy each more than 1,000 times larger than its own. A century ago, Bhutan’s first monarch signed a treaty making it a protectorate of India, then under British rule.

Four kings and two updates of the treaty later, Bhutan no longer defers to India for foreign policy decisions. But New Delhi still retains such influence that the sprawling Indian embassy in Thimphu, the capital, is sometimes referred to as the Sixth King.

The arrangement has generally benefited Bhutan. In sleepy Thimphu, store shelves are stocked with consumer goods from India, brought in on Indian trucks along winding roads paved by Indian army construction crews. India is both the builder and customer of Bhutan’s main industry, hydroelectric power, and the source of 70% of its tourism, the second biggest earner.

In 1999, when the royal family finally lifted a ban on television, Bollywood movie channels quickly became the biggest entertainment force in the kingdom.

There is little natural affinity for China, located on the other side of the Himalayas and seen as pursuing a breakneck style of development that is at odds with Bhutan’s more modest, environmentally friendly ambitions.

“India has carried us,” said Sanjit Mohat, a 25-year-old business student. “We don’t see any trade with China. We don’t want to be a country with tall buildings. We want to be happy.”

Bhutan and China have held two dozen rounds of border talks, but Bhutan has refused to cede the plateau it calls Dolam, and which China refers to as Donglang. Many analysts believe Bhutan is protecting the interests of India, which regards the plateau as strategically vital, close to a narrow corridor known as the “chicken’s neck” that connects the Indian mainland to eight distant northeastern states.

Many Bhutanese also distrust China for its 1951 annexation of Tibet, the vast Buddhist region that once encompassed Bhutan.

Although Bhutanese Buddhists follow their own spiritual guides, they respect the Dalai Lama, the Tibetan leader who lives in exile in India. His familiar bespectacled face smiled down from above a kiosk at a mall in Thimphu, where 23-year-old Sonam Wangchuk was selling Internet scratch cards.

“We have a long relationship with India,” said Wangchuk, who wore a T-shirt with an illustration of the Taj Mahal. “We have to be careful with China.”

One floor above, Ugyen Tashi sat in an empty classroom in the language institute he opened last year. Tashi, who studied Buddhism in Taiwan, launched one of Thimphu’s first Chinese language courses but was contemplating shutting it down due to a lack of interest.

Only about 20 people had signed up for the month-long class over the past year, he said. Although Chinese make up the second largest group of foreign tourists to Bhutan, they tend to come with their own Mandarin-speaking guides.

“No Bhutanese wants to learn Chinese,” Tashi said. And there was no need for classes to cater to Indian visitors, he said — thanks to Indian television, “everyone already knows Hindi.”

Still, some Bhutanese have begun to chafe inside the tight embrace of big brother India. Bhutan joined the United Nations in 1971, and a decade ago the fourth king ceded executive power to a democratically elected parliament, fueling a desire among educated Bhutanese for a greater say in their country’s affairs.

To them, India’s decision to send soldiers into a China-Bhutan dispute smacks of neo-colonialism. It remains unclear whether Indian officials told Bhutan they were deploying troops to Dolam.

“When India says they did this to protect us, I feel insulted,” said Dawa Penjor, executive director of the Bhutan Media Foundation, a nonprofit organization working to develop a free press in the kingdom.

“India should realize Bhutan is a sovereign nation and can take care of itself. Because India lacked diplomacy, they couldn’t influence other countries in the region. But they can’t use Bhutan to start a conflict with China.”

Strains in the relationship began to show in 2012, when then-Bhutanese Prime Minister Jigme Yozer Thinley held a meeting with his Chinese counterpart without notifying India beforehand. A year later, as Thinley was seeking re-election, India abruptly withdrew gas and kerosene subsidies to Bhutan, creating an economic panic that helped lead to his defeat.

The Indian meddling deeply unsettled Bhutanese officials, who have begun pushing back.

When India proposed a four-nation regional road compact – a poor man’s version of China’s mammoth Belt and Road Initiative that India and Bhutan have boycotted – Bhutan opted out, saying it would create too much traffic. Bhutan also refused to sign contracts for four joint hydroelectric projects because it regarded the terms as overly favorable to India.

This year, after the Indian army put up a sign outside the international airport that read, “Dantak welcomes you to Bhutan” – referring to the army’s road-building initiative in the country – annoyed Bhutanese officials had the word “Dantak” painted over.

“Bhutan has every reason to be grateful to India, but these small games they play really antagonize us,” said Yeshey Dorji, a photographer and blogger.

“As much as I want to love India, they are slowly driving the Bhutanese toward China.”

To Dorji and others, establishing ties with Beijing is important to promote Bhutan’s sovereignty and reduce economic dependence. They cite the example of next-door Nepal, another landlocked nation that has periodically been brought to its knees by Indian blockades.

For China, peeling Bhutan away from India is part of its march toward unquestioned dominance in Asia – its version of the 19th century Monroe Doctrine, under which the U.S. declared its opposition to European colonial powers exerting influence in the Western Hemisphere.

“What Beijing is saying to Bhutan is, ‘How’s that special relationship with India working out for you? Can India really protect you?’” said John Garver, an expert on Chinese foreign policy at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

“China is determined that there be no barriers to the growth of its influence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region.… China understands that if it’s not preeminent in South Asia it will not be a global rival to the United States.”

As Bhutan’s strategic importance grows, it is likely to face growing pressure from China and India — both of which said Monday that their armies would continue to patrol the Dolam plateau, whose status remains unsettled. The standoff might be over, but calm has not been restored to the kingdom.

“We still want the border issue to be resolved,” Dorji said. “This respite is pointless for us.”

Follow @SBengali on Twitter for more news from South Asia

ALSO

Pakistan finds itself on the defensive in Trump’s Afghan war strategy

How an L.A. native learned to stop worrying and love — OK, tolerate — India’s monsoon

Singapore has an idea to transform city life — but there may be a privacy cost

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.