Some Mississippi legislative districts dilute Black voting power and must be redrawn, judges say

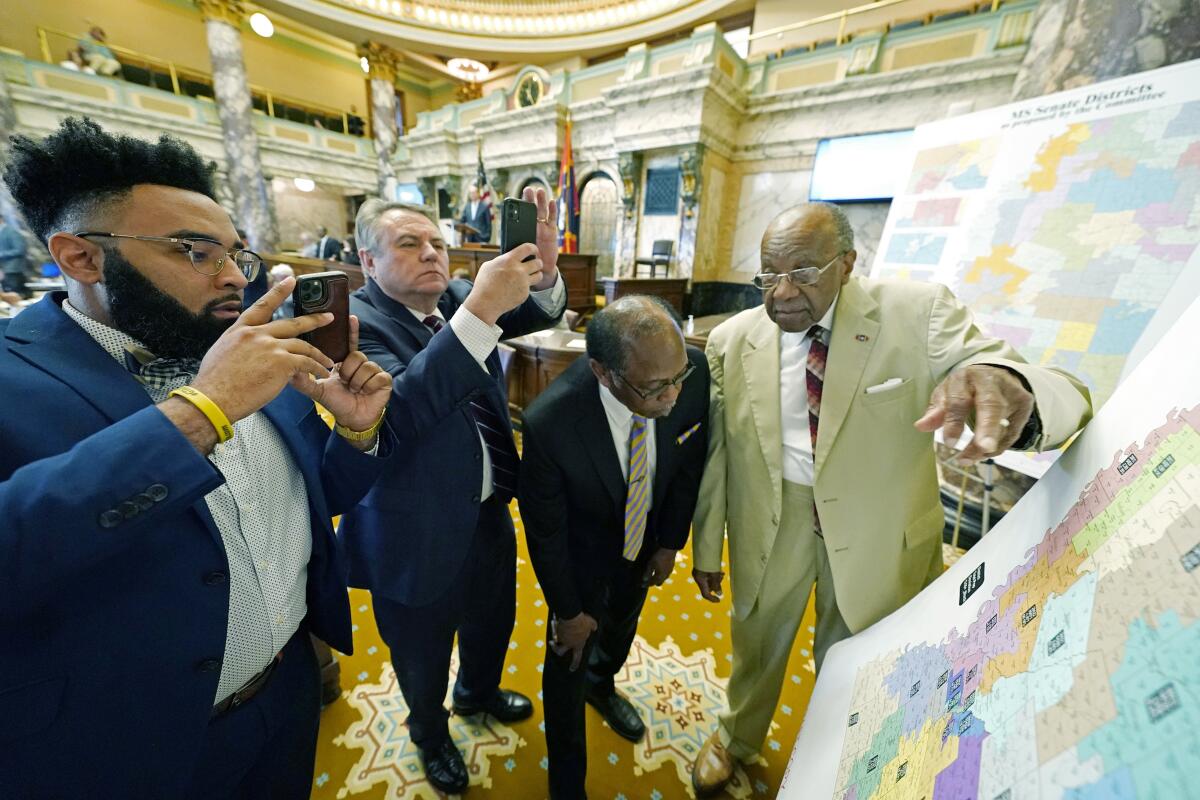

JACKSON, Miss. — Three federal judges are telling Mississippi to redraw some of its legislative districts, saying the current ones dilute the power of Black voters in three parts of the state.

The judges issued their order Tuesday night in response to a lawsuit filed in 2022 by the Mississippi State Conference of the NAACP and several Black residents.

“This is an important victory for Black Mississippians to have an equal and fair opportunity to participate in the political process without their votes being diluted,” one of the plaintiffs’ attorneys, Jennifer Nwachukwu of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, said in a statement Wednesday. “This ruling affirms that the voices of Black Mississippians matter and should be reflected in the state Legislature.”

Mississippi’s population is about 59% white and 38% Black.

In the legislative redistricting plan adopted in 2022, 15 of the 52 Senate districts and 42 of the 122 House districts are majority Black. Those are 29% of Senate districts and 34% of House districts.

The judges ordered legislators to draw majority-Black Senate districts in and around DeSoto County in the northwestern corner of the state and in and around Hattiesburg in the south, and a new majority-Black House district in Chickasaw and Monroe counties in the northeastern part of the state.

Civil rights activists and some lawmakers are concerned that new redistricting maps in three Southern states will dilute the voices of Black people.

The order does not create additional districts. Rather, it would require legislators to adjust the boundaries of existing districts. That means multiple districts could be affected.

The Mississippi attorney general’s office was reviewing the judges’ ruling Wednesday, spokesperson MaryAsa Lee said. It was not immediately clear whether the state would appeal it.

Legislative and congressional districts are updated after each census to reflect population changes from the previous decade. Mississippi’s new legislative districts were used when all of the state House and Senate seats were on the ballot in 2023.

Tommie Cardin, an attorney for state officials, told the federal judges in February that Mississippi cannot ignore its history of racial division, but that voter behavior now is driven by party affiliation, not race.

“The days of voter suppression and intimidation are, thankfully, behind us,” Cardin said.

Reversing a decision by two Trump-appointed judges, the Supreme Court restores a voting-rights victory in Louisiana.

Historical voting patterns in Mississippi show that districts with higher populations of white residents tend to lean toward Republicans and that districts with higher populations of Black residents tend to lean toward Democrats.

Lawsuits in several states have challenged the composition of congressional or state legislative districts drawn after the 2020 census.

Louisiana legislators redrew the state’s six U.S. House districts in January to create two majority-Black districts, rather than one, after a federal judge ruled that the state’s previous plan diluted the voting power of Black residents, who make up about one-third of the state’s population.

And a federal judge ruled in early February that the Louisiana legislators diluted Black voting strength with the state House and Senate districts they redrew in 2022.

In December, a federal judge accepted new Georgia congressional and legislative districts that protect Republican partisan advantages. The judge said the creation of new majority-Black districts solved the illegal minority vote dilution that led him to order maps to be redrawn.

Wagster Pettus writes for the Associated Press.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.