Behind a prosecutor’s push to arrest Israeli and Hamas leaders

Over the course of Israel’s devastating 7-month-long war with Hamas, a fierce parallel battle has been playing out over various international legal mechanisms for holding individuals accountable.

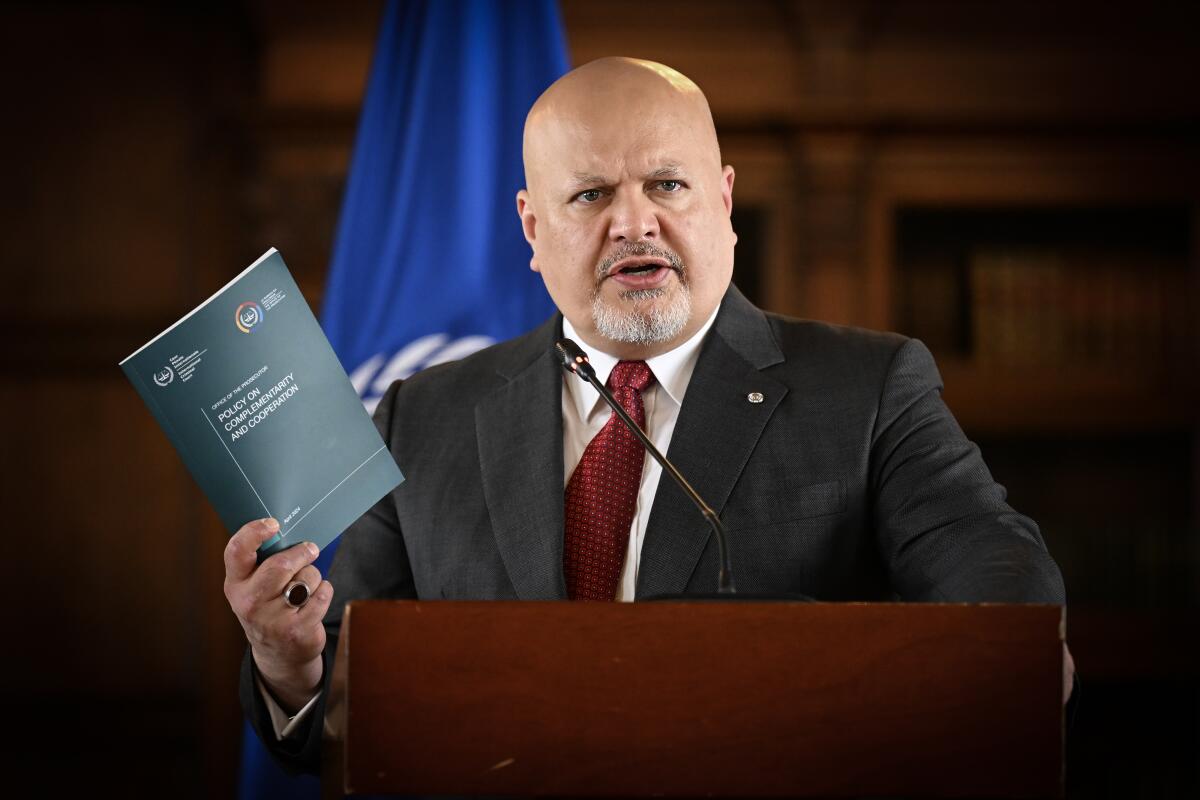

On Monday, Karim Khan, the lead prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, announced that he would request arrest warrants for the Israeli prime minister, the country’s defense minister and three senior figures from the militant Palestinian group Hamas in connection with alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Here is some background about Monday’s move:

Who are those named in the warrant application?

Benjamin Netanyahu: The Israeli prime minister, the country’s longest-serving leader and the head of the most right-wing government in Israel’s history, orchestrated his government’s response to the Oct. 7 Hamas-led attack that killed about 1,200 people in southern Israel. Netanyahu has resisted increasing pressure by the Biden administration and governments around the world to halt Israel’s military onslaught in Gaza, which Israel says is aimed at destroying Hamas and rescuing scores of people who were taken hostage — but which Palestinians call a genocide.

For the record:

5:18 p.m. May 21, 2024An earlier version of this story incorrectly said that Yahya Sinwar, a senior figure in Hamas, was released from an Israeli prison in 2022. He was released in 2011.

Yahya Sinwar: A Hamas member since the 1980s who climbed its ranks through a combination of military ingenuity and extreme brutality, Sinwar is considered the prime mastermind behind the Oct. 7 attack. After long stints in Israeli military prisons during which he became fluent in Hebrew, he was released in a prisoner swap in 2011. Sinwar, a Gaza native whose family was displaced during Israel’s war of independence, tops Israel’s most-wanted lists but has managed to evade death or capture by taking refuge in Hamas’ underground tunnel network. Israel has called him a “dead man walking.”

Ismail Haniyeh: Hamas’ supreme leader, Haniyeh is based in Qatar, a Gulf state that has aided in mediation efforts. In his capacity as the group’s political chief, he frequently travels around the region. Last month, Haniyeh said three of his sons and four grandchildren were killed in an Israeli airstrike in Gaza. He called them martyrs. The Israeli military said slain sons were members of Hamas’ military wing, which Haniyeh denied.

The demonstrations over Israel’s war in Gaza are intense. But how deep and long-lasting is their staying power in U.S. politics?

Mohammed Deif: A top Hamas military commander left maimed by repeated Israeli attempts on his life, Deif is by far the most shadowy figure of those named by the ICC prosecutor. He is known as a longtime overseer of the group’s bomb-making capability, directing dozens of suicide bombings of Israeli buses and cafes in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Yoav Gallant: The Israeli defense minister is a member of Netanyahu’s conservative Likud party as well as Israel’s so-called war Cabinet formed after Oct. 7. Gallant has come under outside scrutiny for declaring early on in the fighting that Israel would impose a full food and fuel blockade on Gaza as well as his use of the term “human animals,” which Israel said was intended to describe Hamas, not all Palestinians. Gallant, whom Netanyahu moved to oust before the war began, has repeatedly tangled with the prime minister, most recently declaring that he would not support an open-ended military occupation of Gaza.

What do Israel and Hamas say?

Israel responded to the prosecutor’s announcement with fury, denouncing it as a rejection of its right to self-defense in the wake of the Oct. 7 attack.

In a blistering statement, Netanyahu called the warrant request “absurd and false,” and said it was directed against Israel as a whole. He also insisted it would not alter Israel’s war aims. Foreign Minister Israel Katz called the prosecutor’s announcement a “historic disgrace” and said a special panel would be set up to contest any further moves by the court to target Israeli leaders or officials.

Hamas also denounced the warrant request. In a statement on the messaging app Telegram, it said Israeli leaders as well as individual military officers and soldiers bore responsibility for “crimes against the Palestinian people.” A senior Hamas official, speaking to the Reuters news agency on condition of anonymity, also blasted the ICC prosecutor’s move, saying it “equates victim with executioner.”

What has the United States government said?

President Biden called the warrant request “outrageous” and said it created a false equivalence between Israel and Hamas. His administration also said the application could jeopardize efforts to reach a cease-fire agreement, strike a deal on releasing the hostages and step up humanitarian assistance to Palestinians in Gaza.

What exactly did the prosecutor say?

Khan’s statement, which casts blame on both Israel and Hamas, declared that “international law and the laws of armed conflict apply to all,” adding that “no foot soldier, no commander, no civilian leader — no one — can act with impunity.” The prosecutor said the right to self-defense does not absolve Israel of obligations to comply with international humanitarian law.

“Notwithstanding any military goals they may have, the means Israel chose to achieve them in Gaza — namely, intentionally causing death, starvation, great suffering, and serious injury to body or health of the civilian population — are criminal,” he wrote.

The tiny Persian Gulf nation initially had success persuading Hamas to give up hostages. Critics claim its influence and commitment have diminished.

Khan’s warrant request also takes detailed aim at Hamas, describing direct evidence of killings, sexual violence and torture perpetrated by the Oct. 7 attackers. In the announcement, he cites the “profound impact of the unconscionable crimes,” including “unfathomable pain through calculated cruelty and extreme callousness.”

“These acts demand accountability,” he wrote. Khan and an investigative team visited the West Bank and Israel in December, but did not enter Gaza.

In making his decision to pursue the arrest warrants, Khan consulted with a panel of international law experts. They included London-based human rights lawyer Amal Clooney, who said in a statement published on the website of the Clooney Foundation for Justice that the panel’s findings were unanimous.

What happens next?

It’s possible that the warrants won’t end up being issued, although Khan’s announcement suggests confidence that they will. A panel of three pretrial judges first needs to weigh the evidence and render a decision. There’s no set deadline for that, and it could take months.

Even if warrants are issued, none of the accused face much possibility of arrest unless they travel to any of the 124 countries that recognize the jurisdiction of the ICC. Israel and the United States are not signatories to the ICC, but most European countries are.

The court does not allow trials in absentia. But particularly in the case of a sitting head of state or senior official, an indictment of this kind deepens international isolation.

Has the ICC taken similar actions in other conflicts?

Monday’s announcement is reminiscent of ICC judges’ move 14 months ago against Russian President Vladimir Putin, whose forces launched a full-scale invasion of neighboring Ukraine 27 months ago. The arrest warrant cited the abduction of Ukrainian children into Russia, but did not address many other alleged Russian atrocities that have taken place during the course of the war.

Though the United States is not a signatory to the treaty setting up the ICC, Washington sometimes cooperates with the court. For example, on Monday, Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III said the United States was continuing to provide evidence to the ICC regarding Russian war crimes in Ukraine.

Is this related to the genocide case against Israel?

Not really, even if it largely centers on the same events. The ICC, which was set up in 2002 to adjudicate cases of individuals accused of war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity, is different than the International Court of Justice, though both are based in The Hague. The latter is weighing a much-watched claim brought by South Africa that Israel is carrying out a genocide in Gaza. Israel is vociferously contesting that accusation.

What’s happening on the ground in Gaza?

The ICC prosecutor’s move comes against the backdrop of a new push by Israeli ground forces on Monday in central Gaza and Israeli bombardment in the territory’s north. Israel has also signaled its intent to widen its incursion into Rafah, a Gazan city on the border with Egypt where hundreds of thousands of Palestinians have sought haven.

At UCLA, the legacy of the encampment remains an issue of much debate, particularly among Jewish students.

Israel says it is pursuing Hamas into its main remaining strongholds, but the United States and many other Western governments and humanitarian groups have warned that a full-on Israeli offensive in Rafah would likely cause enormous civilian casualties.

Meanwhile, famine threatens about half of Gaza’s more than 2 million inhabitants, according to the United Nations and other groups. Large portions of the narrow, 25-mile-long territory have been leveled by aerial bombardment or wrecked in Israeli ground incursions. The healthcare system hardly exists, and about four-fifths of the population is displaced. In addition to some 35,000 Palestinians killed, according to a U.N. count, thousands more are still believed buried under tons of rubble.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.