Kate’s remarkable video was a Royal revolution, scepter-spinning in its frankness

Somewhere in the oversharing universe of social media, there still are to be found the cranky netizens who suspiciously believe that they aren’t being told everything about what really ails Catherine, the Princess of Wales, and that they should be — and while they’re at it, c’mon, what’s the actual deal about King Charles and cancer?

Just as no facts are ever enough to satisfy conspiracy theorists, no amount of information is ever enough to quench the online gossipy thirst about the royal family.

But the remarkable two-minute, 13-second video of a composed Princess of Wales — the queen in waiting, the wife and mother of future kings — speaking the word “cancer” about her own health has come as close to shutting it down as is reasonably possible.

An in-the-know friend in London told me that the day after the video was released, the rumor mills were stilled. No sniggering jokes now about princely flings and sulky princesses and body doubles. The tabloids are for the moment chastened into delivering bended-knee good wishes in large type.

Catherine, Princess of Wales, has an undisclosed form of cancer. She announced the news online after months of speculation about her health and whereabouts.

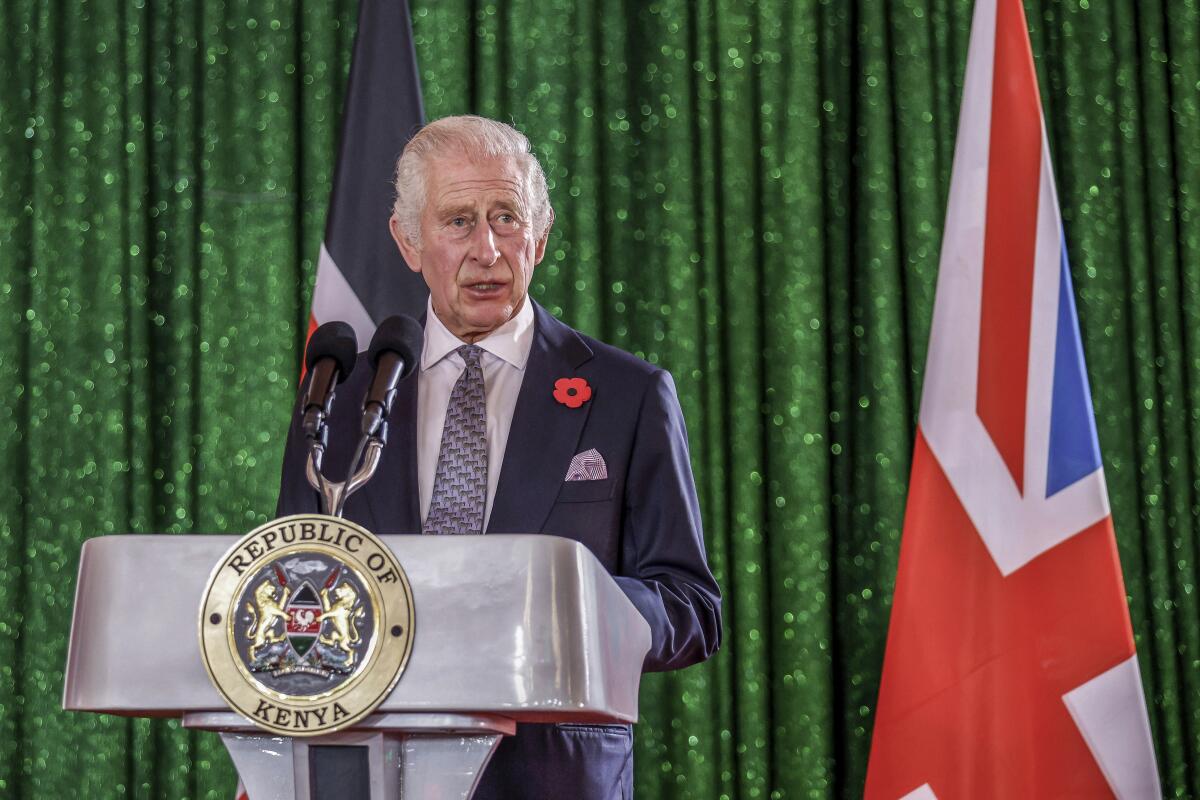

The sovereign holds a constitutional role in Britain, and King Charles’ unspecific cancer announcement — maybe not a huge surprise for a man in his 70s — had political and emotional resonance for his country. But the same news from Princess Kate — a fit, healthy-looking mother of three young children, and herself only a few years older than the last Princess of Wales when she died in a car crash — carried shock value.

Catherine’s video is the kind of thing that the rest of us might post on our Facebook groups if we found that we had cancer.

But from the royal vantage point, it was a scepter-spinningly frank act. That royal vantage point isn’t our yardstick. Our measures change by days; their measures — and strategies, not always wisely — by decades.

Only 70-some years ago, the king of England had lung cancer — and his doctors did not tell even him. On Sept. 23, 1951, King George VI, King Charles’ grandfather, had surgery to remove much of his left lung, but the word “cancer” was not used. Instead, the doctors’ euphemism was “structural abnormalities.”

The video announcement by Catherine, Princess of Wales, about her cancer diagnosis was short on specifics. Here’s a look at what we know.

Hours afterward, a gilt-framed notice posted on the Buckingham Palace gates was signed by eight physicians and blandly read, “The King underwent an operation for lung resection this morning. Whilst anxiety must remain for some days, His Majesty’s immediate post-operative condition is satisfactory.” For several hours, Londoners queued up two abreast to read the hand-lettered notice. (Smoking figured in the deaths of Windsor men — Kings Edward VII, George V, Edward VIII and George VI all smoked from an early age. Palace inventories list gold and jeweled cigarette cases as gifts to royal men, even in their teens.)

It was only since 1932 that Britons had been hearing their kings’ actual voices, in an annual Christmas radio speech. Posting personal news on the Buckingham Palace gates was Windsor Twitter, the way the family had announced births and other family developments since at least Queen Victoria’s time.

So the intimacy of a video of the future queen wearing jeans and a sweater, sitting on a garden bench talking about her own illness, may look like the natural thing to do to our 21st-century selves. But it’s a quantum hurdle for the royal family — and, this time, a constructive one.

Kate Middleton emphasized the time she took to share her cancer diagnosis with her children. Here’s how adults can speak to children about serious illnesses.

The last time such personal televised revelations came from a senior royal was Princess Diana’s ill-starred BBC “Panorama” interview. In it, she questioned Prince Charles’ fitness to be king.

She won the public’s PR battle of the moment, but lost the war. Queen Elizabeth II soon told Charles and Diana that they should divorce ASAP.

King George VI died in his sleep almost five months after his lung surgery. By then, he’d grown so gaunt and haggard-looking that makeup was sometimes applied to his face to give him a more robust look in public.

In virtually any age and any culture, the health of the king was the health of the kingdom.

A sickly monarch couldn’t lead troops to victory. A sickly monarch generated rumors about his longevity, and the stability of his rule. Queen Elizabeth I’s elaborate mask-like daily makeup ritual not only hid her smallpox scars but was also meant to project a preternatural agelessness.

In the 15th century, the befuddled derangement of the English King Henry VI — possibly a hereditary schizophrenia — helped to light the fuse of the Wars of the Roses.

And it wasn’t the monarch’s health alone that mattered, but the royal family’s. In the 20th century, the secret hemophilia of the heir to the Russian empire had a hand in driving the Romanov dynasty to oblivion.

Royal well-being was so deadly serious that a 1352 English law made it high treason to plan the death of the king, the queen, or the heir to the throne. The paranoid King Henry VIII expanded the definition to include words, not just actions. Even casting the monarch’s horoscope was treasonous, and treason’s death sentence was hideous: women were burned alive, men were hanged, drawn, and quartered — hanged until almost dead, eviscerated while still alive, then chopped into pieces.

The fact that Elizabeth II lived until the age of 96, and died within 48 hours of her last official engagement, had in it a touch of the mystical perpetuity of sovereignty. The final public medical report of her life, her cause of death, was “old age.” The first public medical report about her was to explain how she came into the world. “A certain line of treatment was successfully adopted,” was the euphemism that the palace deployed to explain that the future Elizabeth II arrived by C-section. To us, it sounds comically quaint; Queen Victoria would have plotzed from mortification.

One of Elizabeth II’s wry maxims was, “I have to be seen to be believed.” But she was also taught a Victorian scholar’s contradictory maxim that monarchy’s intangible strength is magic, and “we must not let in daylight upon magic.”

Royals have always struggled with this balancing act. Queen Victoria came in for relentless criticism for hiding away in her widowhood for 40 years, dodging public engagements, not giving “value for money” by keeping the glittering royal show wrapped in mourning. Most dangerously to the crown, as the liberal politician and social activist Charles Bradlaugh wrote around 1870, her absence “proved that the country can do quite well without a monarch and therefore save the extra expense of monarchy.”

A year or so after Bradlaugh wrote that, Victoria’s heir, the Prince of Wales, nearly died from typhoid, and the general relief and rejoicing at his recovery buoyed the monarchy’s standing anew. Would such a phenomenon happen again, 150 years later?

The Princess Kate video was wise to that past, and this present. A framed announcement at the palace gates would simply not do, especially not after “Kate-Gate.” The Photoshopped image that showed a smiling princess who had been out of the public eye was crafted not so much out of a zeal for amateur photography as from the royals’ intent to protect their privacy and to stop the undertow of rumors.

Naturally these royals want to control the narrative, with their own photos, photo ops, and selective release of information. For crikey’s sake: someone eavesdropped and taped Charles’ saucy phone calls with his then-mistress, Camilla; someone did the same with Diana’s phone calls with a rumored boyfriend. Princes William and Harry’s voicemail messages were hacked by a tabloid, and the palace was told of an alleged plot to steal some of the teenaged Harry’s hair to test against rumors that his father was not Prince Charles.

And there’s a current investigation into whether medical staffers tried to look at Catherine’s records while she was hospitalized in January for the abdominal surgery that would reveal her cancer. (UCLA Health System had to pay huge fines after employees illicitly peeked at celebrities’ records.)

Who among us wouldn’t want to build a virtual fence to keep out that?

But as any veteran Hollywood PR pro could tell the royals — even if their own palace staff won’t — it’s impossible. They do have to be seen to be believed, and not just on their own terms. The Princess of Wales’ manipulated photo with her children was killed by news photo agencies, and Kensington Palace was put on the not-trusted source list by a major news agency. That’s why last Friday’s video was not a home-movie creation. It was shot by BBC Studios and accompanied by a BBC announcement that it had not been edited.

Many will shame royal watchers for speculating about the Princess of Wales’ health. But catastrophic missteps by the royal communications apparatus created this mess.

The enormity of Catherine’s cancer diagnosis, and her plea for “time, space and privacy,” have eclipsed the venial sins of Kate-Gate. Nothing can keep social media in line, but this crisis moment for the House of Windsor might be an opportunity to reset press-palace media relations.

Catherine’s video statement did not use words like “victims,” or “battling” or “fighting” cancer. She spoke, instead, to “everyone facing this disease” or “affected by cancer.”

In the fullness of time, when Kensington Palace decides to let the world know what kind of cancer it was, that information may accomplish for her specific cancer what the revelation of King Charles’ prostate treatment did: It sent hundreds of thousands of Britons to their doctors for checkups and saved perhaps thousands of British lives — as many as and maybe more than any king of England bearing sword and shield ever saved in battle.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.