Why thousands of junior doctors in South Korea are striking, and what it means for patients

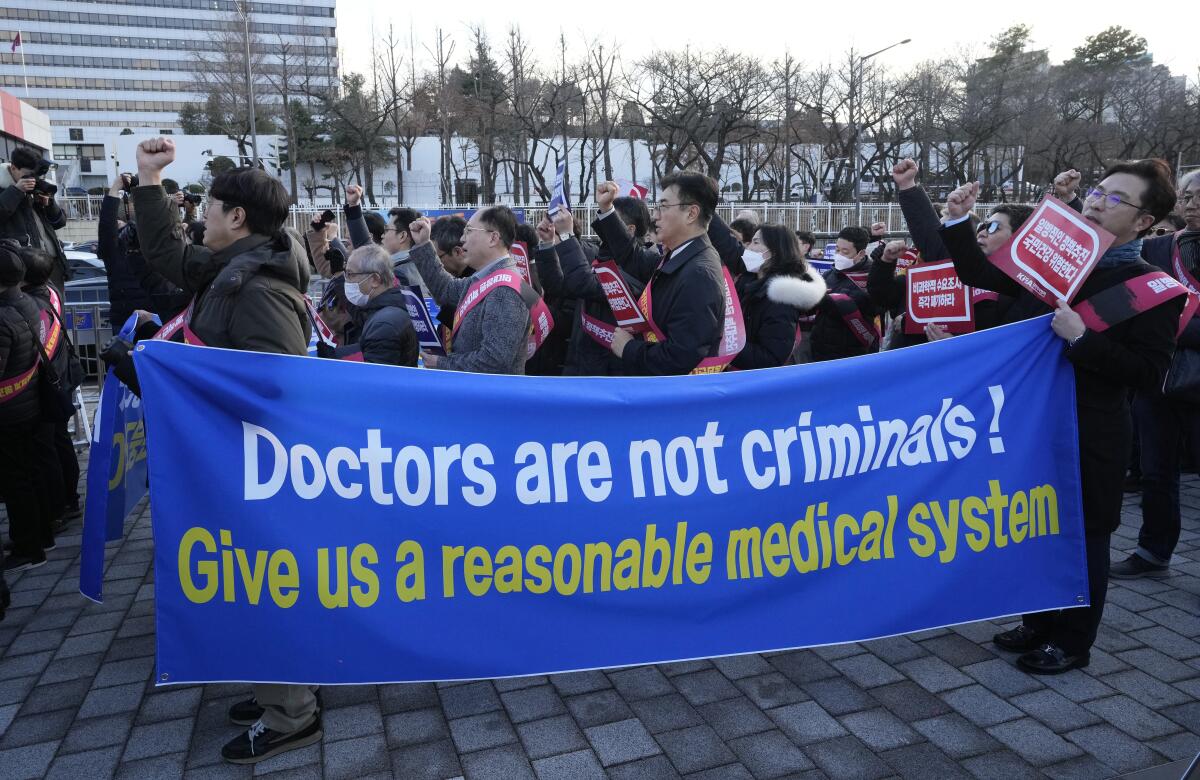

SEOUL — Thousands of junior doctors in South Korea have been refusing to see patients and attend surgeries since they walked off the job Feb. 20 in response to the government’s push to recruit more medical students.

As of Tuesday, about 8,940 medical interns and residents have left their worksites in protest, disrupting the operations of major hospitals in South Korea and threatening to burden the country’s overall medical service. Now, authorities warn that they have until Thursday to return to work or face license suspensions and prosecutions.

Here’s what’s happening with the strikes:

Why are doctors striking?

The government plans to raise South Korea’s yearly medical school admission caps by 2,000, from 3,058.

The enrollment plan is meant to add up to 10,000 doctors by 2035 to cope with the country’s fast-aging population.

Officials say South Korea has 2.1 physicians per 1,000 people — far below the average of 3.7 in the developed world.

As South Korea hits the world’s lowest birth rate, a rural elementary school struggles to stay open amid a nationwide drop-off in school-age children.

The striking doctors-in-training say schools can’t handle an abruptly increased number of medical students. They predict doctors in greater competition would perform overtreatment — increasing public medical expenses — and, like current medical students, most of the additionally recruited medical students would also probably try to work in high-paying, popular professions such as plastic surgery and dermatology.

That means the country’s long-running shortage of physicians in essential yet low-paying areas including pediatrics, obstetrics and emergency departments would remain unchanged.

Some critics say the striking junior doctors simply oppose the government plan because they worry adding more doctors would result in lower income.

Ahn Cheol-soo, a doctor-turned-lawmaker in the ruling party, said on a local TV program that he supports the government’s plan.

But without fundamental steps to convince students to opt for the essential areas, Ahn said that “2,000 new dermatology hospitals will be established in Seoul 10 years later.”

With South Korea’s birthrate plummeting, veterans in their 60s and 70s say they can bolster the army’s ranks. But can they keep up with the young?

What do the strikes mean for patients?

The walkouts have led hospitals to cancel numerous planned surgeries and other medical treatments. On Friday, an octogenarian in cardiac arrest was reportedly declared dead after seven hospitals turned her away, citing a lack of medical staff or other reasons probably related to the walkouts.

In some major hospitals, junior doctors account for about 30% to 40% of the total doctors, playing the role of supporting senior doctors during surgeries and dealing with inpatients. The strikers are among the country’s 13,000 medical residents and interns, and they work and train at about 100 hospitals in South Korea.

In the wake of the walkouts, the government has extended the working hours for public medical institutions, opened emergency rooms at military hospitals to the public, and given nurses legal protection to conduct some medical procedures typically done by doctors.

As South Korea’s migrant labor program ramps up recruitment, it faces scrutiny for what critics say is a failure to guarantee safe working conditions.

Vice Health Minister Park Min-soo said Tuesday that the country’s handling of critical and emergency patients largely remains stable. But observers say the country’s overall medical service would suffer a major blow if the walkouts became prolonged, or if senior doctors join the strike.

The Korea Medical Assn., which represents about 140,000 doctors in the country, has steadfastly expressed its support of the trainee doctors, though it hasn’t determined whether to join their walkouts.

Park Jiyong, a spine surgeon in South Korea, said senior doctors at major university hospitals will probably join the walkout in coming days, which would “virtually collapse the operations of those hospitals.”

What’s next?

On Monday, Park, the vice health minister, said the government won’t seek any disciplinary steps against the striking doctors if they report back to work by Thursday. But, he warned, anyone who missed the deadline would be punished with a minimum three-month suspension of their medical licenses and face further legal steps, such as investigations and indictments by prosecutors.

Still, the strikers are unlikely to back down soon.

South Korea’s medical law allows the government to issue back-to-work orders to doctors when it sees grave risks to public health. Those who refuse to abide by such orders risk getting their medical licenses suspended for up to one year and can also face up to three years in prison or a roughly $22,500 fine. Those who receive prison sentences would be stripped of their medical licenses.

Some observers say authorities will probably limit punishment to strike leaders for fear of a further strain on hospital operations.

Doctors are among the highest-paid professionals in South Korea, and the trainees’ walkout has so far failed to win public support, with a survey showing that about 80% of respondents support the government’s recruitment plan.

“What if your mother has to get an injection or die? It seems like those doctors never were in others’ shoes but are only emotional,” said Kim Myung-ae, a 57-year-old cancer patient. “They don’t care about the patients but only the benefits they get as doctors in this country.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.