The people of Gaza have lived for more than two months under the constant specter of death. Shaken by falling bombs, surrounded by advancing troops and grieving the loss of loved ones, they have communicated with the rest of the world mainly through social media — as long as the internet is working.

Their messages have been sporadic amid Israel’s ongoing airstrikes and invasion in response to Hamas’ deadly Oct. 7 attack on Israeli civilians. According to their respective governments, about 1,200 people have been killed in Israel; in Gaza, close to 19,000.

Through posts on TikTok, X (formerly Twitter), Facebook and Instagram, Gaza residents have offered glimpses at life in this war zone. Presuming their own deaths are imminent, they have written what could be their last words. They consist of pleas for help, defiant outbursts and many ways of saying goodbye.

Dressed in dark blue scrubs, a stethoscope slung over his shoulders, Husam Almanassra looks worn down in the selfie he posted to X on Nov. 5.

“Before the war I had these high ambitions. Big dreams I was fighting to achieve,” Almanassra, who is an anesthesiologist and intensive care doctor at Shifa Hospital according to his profile, captioned the photo. “But these days … the entire world is just leaving you to die.”

He’s still active online, but The Times was unable to reach Almanassra directly for comment. However, Abdelrahman Abu Shawish — a doctor in the Aqsa Martyrs Hospital surgery department — confirmed the authenticity of Almanassra’s X account and said his colleague survived Israel’s raid on Shifa.

“Husam is fine,” Shawish said on Nov. 21 via direct message. “He’s in one of the [United Nations] shelters after he left the hospital.”

Dozens of cats, of all colors and sizes, lounge around a sparsely furnished room, sleeping and scratching and picking at food from a plate on the floor. Maryam Hasan moves among them in a bright tunic and hijab, cleaning up, stopping to play or give a hug.

Calling herself “a friend of the homeless animals,” Hasan has attracted a social media following through her short videos — often accompanied by jangly pop music — that feature cats she rescues and cares for in her Gaza City residence. Since the war began, her posts have been sporadic.

Living in a neighborhood where, she says, homes have been destroyed by bombing, Hasan wrote on Nov. 22 that “the situation is worse than you think, I am still in danger, I have not left the northern Gaza Strip, more relatives are dead.”

The “terrible pressure” she feels is not limited to fears for her own safety.

Since her last communication on Nov. 22, Facebook friends from around the world have typed frantic messages, including reports of renewed bombing in Hasan’s neighborhood. A Dec. 13 post reads: “Has there been any news? Everyone is talking as though she is gone. Please pray she isn’t gone.”

Looking back at the filmmaker and photojournalist Roshdi Sarraj’s social media with the benefit of hindsight, he almost seems to have known how things would end.

He wrote those words on Oct. 9. Days later, he suggested on Facebook that the only time Palestinians would leave Gaza was in death. And he penned another X post on Oct. 17 criticizing Israel for the number of journalists killed in its bombardment.

He would join their ranks days later, struck by shrapnel on Oct. 22 in an Israeli airstrike. His production company Ain Media confirmed his death — “We are all Roshdi now” — and UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay called for an investigation. His Facebook page has become a memorial.

Sarraj leaves behind a wife, Shrouq Aila, whom he met through work, and a daughter, Dania, who turned 1 in early November.

“I never saw him as a husband, because not all husbands are good,” Aila told The Times in a voice message. “ I used to see him as a best friend. … We’d sometimes speak the same sentence at the same time.”

As collapsed buildings and mounds of uncollected trash passed by outside, Al Jazeera correspondent Youmna ElSayed drove with her family from Khan Yunis in the south Gaza Strip back to their apartment in Gaza City.

With several small kids in the backseat, she filmed a video in mid-October documenting the journey: “Yesterday and all night and today in the morning, the bombardments did not stop in the southern parts of the Gaza Strip. … That’s why so many families who have evacuated south are going back now, because at least if we’re going to die, we’re going to die with dignity in our homes.”

After passing by a plume of smoke she said was the aftermath of an airstrike, the reporter and her family ultimately made it home safely. Since then, ElSayed has kept covering the war.

Wearing a bluish flak jacket emblazoned with the word “Press,” she was recently in a Rafah refugee camp reporting on the lack of women’s sanitary products.

Belal Aldabbour was an avid chronicler of Palestinians’ plight even before the war in Gaza began, posting on X about civilian casualties and Israeli settlements. But it wasn’t until Israel’s bombardment of the Gaza Strip began this October that he started talking about not just other people’s deaths, but the possibility of his own.

“Soon, the last sliver of electricity and connection will be exhausted,” he wrote on Oct. 11.

A neurologist, he would continue to post online and make media appearances through mid-October, describing the dire circumstances his Palestinian patients faced: closed pharmacies, dwindling medicine. On Oct. 18, he shared an academic article he’d co-written with a colleague who, he said, had been killed days earlier.

“If I am killed too,” he said, “let it be my last contribution.”

Soon thereafter, the doctor’s social media profile went quiet. It seemed like his worst fears had come to pass.

But by mid-November he was back online, and has remained an active critic of the crisis ever since. The Times was unable to reach Aldabbour himself for comment, but on Nov. 15 a colleague with whom he’d previously co-authored a scientific paper passed along that the doctor had told a friend “الوضع لا يحتمل” — “the situation is unbearable.”

Snapshots from happier times show Bayan AbuSultan dressed in a blue cap and gown, graduating from Al-Azhar University in Gaza. Or sitting at a desk, wearing a blouse and scarf as she begins her new job as the office director for the Falasteniyeh Media Network.

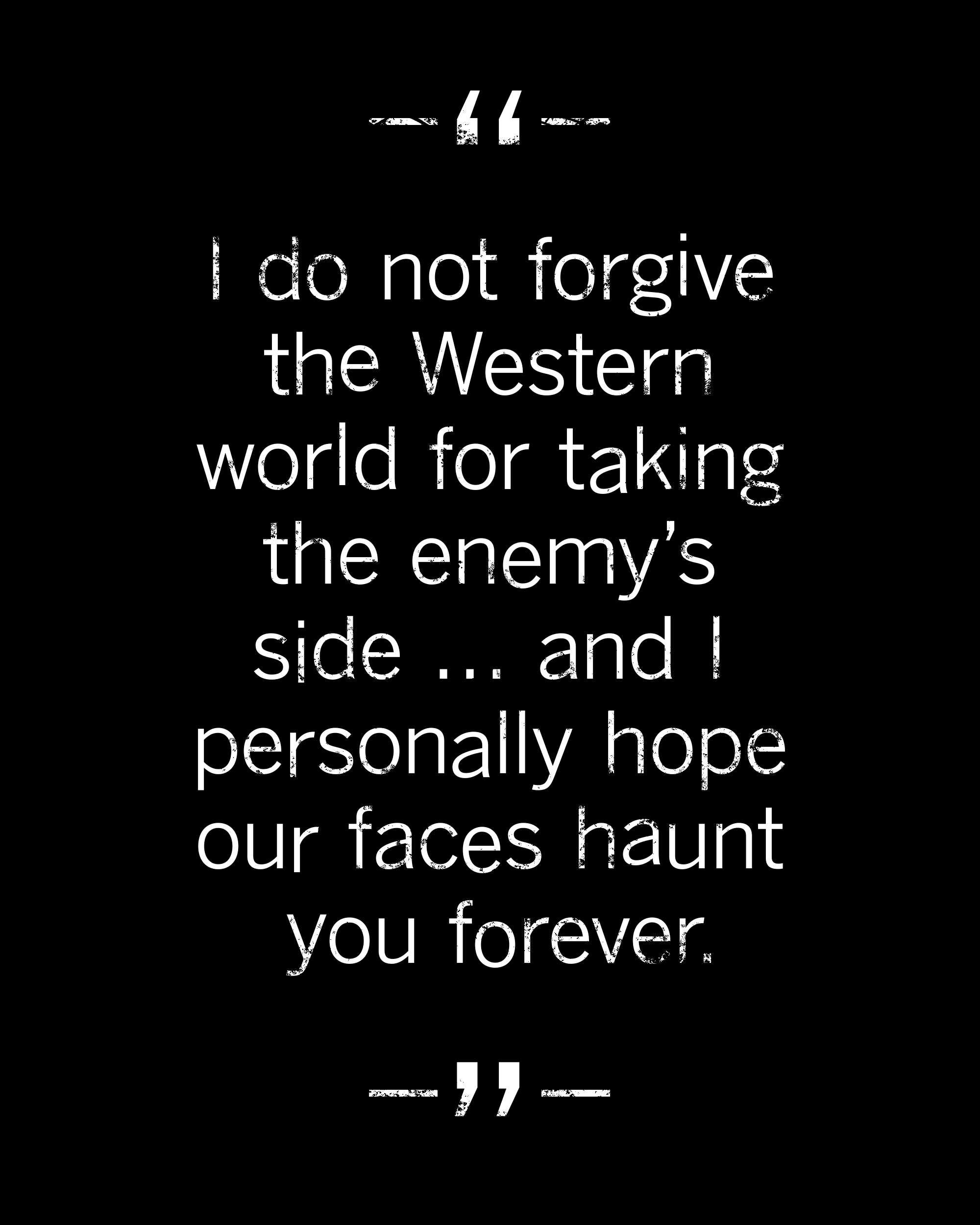

The young woman with long, black hair and a bright smile looks very different in a Facebook video from Oct. 13, the seventh day of the Israel-Hamas war. Speaking from what appears to be a darkened apartment, dressed in a black T-shirt and with a silver necklace, she is quietly defiant. “We don’t know if we’re still going to be alive when there is sunlight again.”

“In case this is my last video and my last message to the world, I would like to say that I do not forgive anyone who could have stopped this bloodshed,” AbuSultan continues.

Her latest post, from Nov. 30, mentions the short-lived truce and a brief respite. She asks if anyone knows someplace in the city where the internet is working.

There have been no posts since then and efforts to reach her have been unsuccessful.

Read more:

‘I just don’t know where we’ll go.’ It’s a question Palestinians ask over and over in Gaza as Israel ramps up bombardment after Hamas truce collapsed.

A forensic investigator in Tel Aviv works to reassemble remains of victims of Hamas militants, trying to understand the causes of death and the underlying cruelty.

A Times special correspondent in Gaza offers a personal account of living in a place where nowhere feels safe.

‘We are surrounded,’ a Palestinian in the occupied West Bank says. Israeli settlers ‘come in uniforms so you can’t tell the difference between settler and soldier.’

The Times gathered a panel of Jewish thinkers to talk about recent incidents and help define what antisemitism is and what antisemitism isn’t.

The Palestinian cause — and hostility toward Israel — has shifted from the sidelines of student activism to a robust political movement at U.S. colleges.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.