U.S. warns of a Chinese global disinformation campaign that could threaten peace and stability

WASHINGTON — For much of the world, China’s Xinjiang region is notorious, a place where ethnic Uyghurs face forced labor and arbitrary detention. But a group of visiting foreign journalists was left with a decidedly different impression.

On a tour in late September sponsored by the Chinese government, the 22 journalists from 17 countries visited bazaars and chatted with residents over dates and watermelon slices. They later told state media that they were impressed with the bustling economy, described the region as “full of cultural, religious and ethnic diversity,” and denounced what they said were lies by Western media.

The trip is an example of what Washington sees as Beijing’s growing efforts to reshape the global narrative on China. It’s spending billions of dollars annually to do so.

In a first-of-its-kind report, the State Department last week laid out Beijing’s tactics and techniques for molding public opinion, such as buying content, creating fake personas to spread its message and using repression to quash unfavorable accounts.

The Global Engagement Center, a State Department agency that’s tasked with combating foreign propaganda and disinformation and that released the 58-page report, warned that Beijing’s information campaign could eventually sway how decisions are made around the world and undermine U.S. interests.

“Unchecked, the [Chinese government’s] information manipulation could in many parts of the world diminish freedom to express views critical of Beijing,” said Jamie Rubin, who heads the center. He said Beijing’s efforts could “transform the global information landscape and damage the security and stability of the United States, its friends and partners.”

Xi Jinping’s Xinhua news agency used my work to help promote its distorted vision of life in the U.S. and China.

“We don’t want to see an Orwellian mix of fact and fiction in our world,” he said. “That will destroy the secure world of rules and rights that the United States and much of the world relies upon.”

China over the weekend slammed the report, calling it “in itself disinformation as it misrepresents facts and truth.”

“In fact, it is the U.S. that invented the weaponizing of the global information space,” the Chinese Foreign Ministry said. It called the State Department agency “a source of disinformation and the command center of ‘perception warfare.’”

In a written statement, Liu Pengyu, spokesman for the Chinese Embassy in Washington, said the report was “just another tool to keep China down and buttress American hegemony.”

China has reportedly established dozens of “overseas police stations” in nations around the world as part of Beijing’s crackdown on corruption.

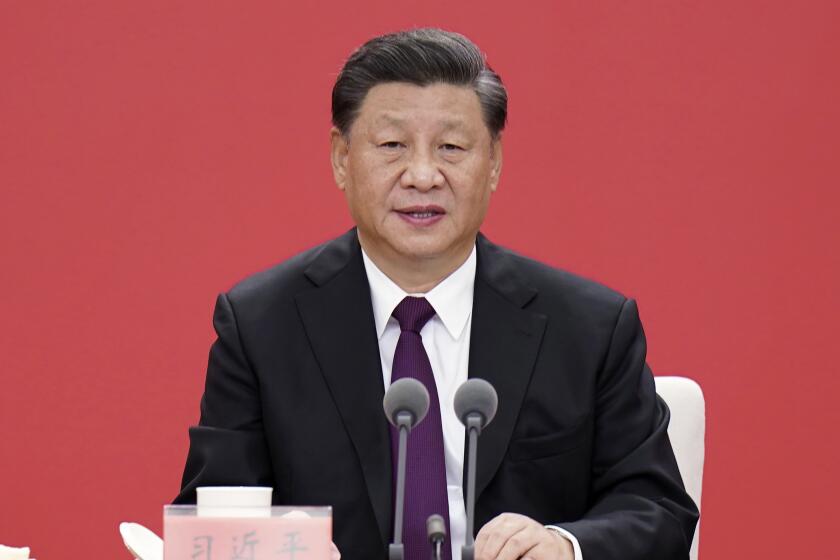

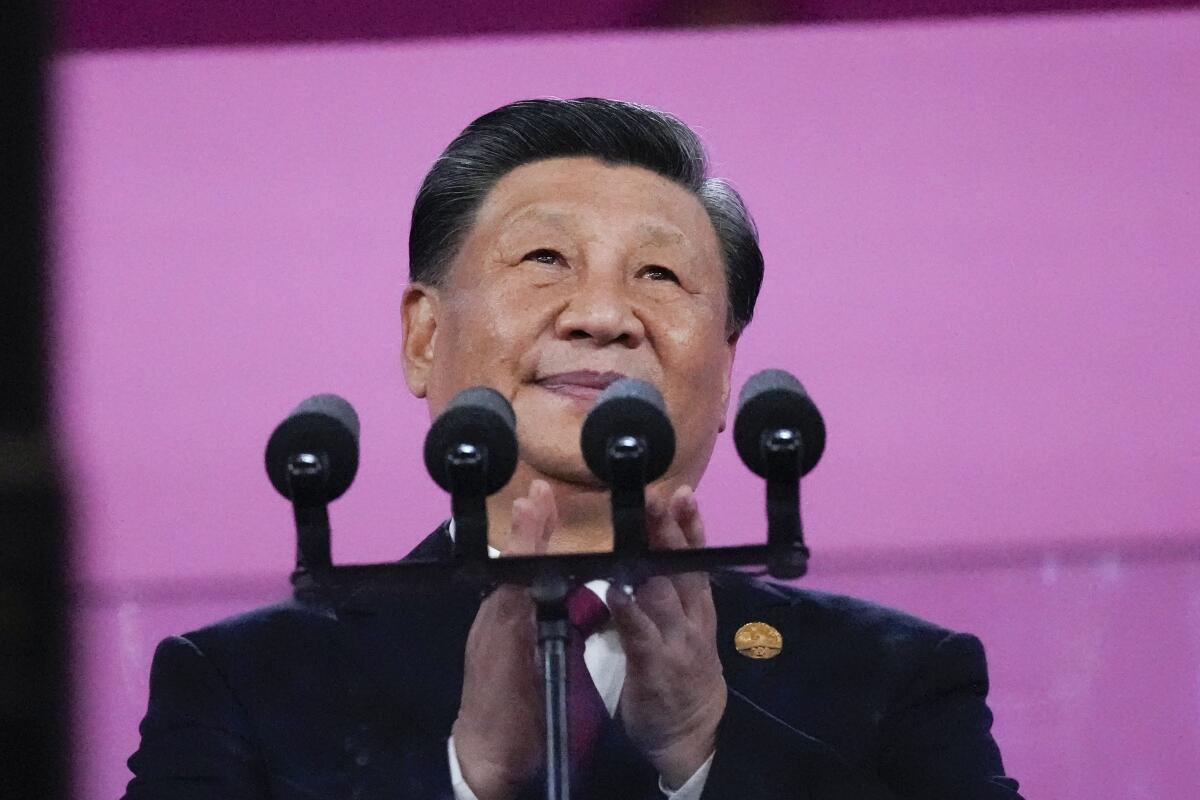

Beijing argues that Western media have long held biases against China and at times have demonized it. Chinese President Xi Jinping has demanded that China tell its story to the world so that Beijing would be trusted and respected.

But U.S. government officials say Beijing is advancing its agenda through coercion and lies. In one case outlined by the report, China created a fake commentator named Yi Fan, whose pro-Beijing writings have appeared in publications in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

In social media, Beijing deploys armies of bots, trolls and coordinated campaigns to suppress critical content and boost pro-Beijing messages, the report states. China-made phones sold overseas have been found to have censorship capabilities.

A national security law in Hong Kong has allowed authorities to prosecute those who live overseas but criticize Beijing’s policy in the territory, according to the report. It also finds that on Ukraine, Beijing has cooperated with Moscow to amplify the Kremlin’s false claims.

With a presidential campaign underway, the island democracy is struggling to deal with a Russian-style disinformation campaign coming from the mainland.

In Xinjiang, Beijing has brought in diplomats and foreign journalists on tightly orchestrated trips with minders in tow.

The aim is to counter allegations that Beijing has mistreated the country’s 11 million ethnic Uyghurs through arbitrary detention and labor programs that send Uyghurs to work in factories far from their homes.

In a report last year, the United Nations said the acts by Beijing in Xinjiang might constitute crimes against humanity. The U.S. government went further, saying the actions constitute genocide against the Uyghurs, most of whom are Muslim.

On the latest such trip to Xinjiang, the journalists praised Beijing’s efforts in preserving the region’s traditional culture, creating a harmonious and prosperous life for people of all ethnicities and religions, the Chinese Communist Party-run Global Times newspaper reported.

Adil Ahmad, 15, has had no contact with his parents since February 2017, when he received a frantic phone call from his mother in the Uighur homeland of China’s western Xinjiang region.

One Iranian journalist described the northwestern region as a beautiful Persian rug with different colors and patterns woven together, according to China News, another state-run news agency.

Meanwhile, Beijing has banned independent reporting in Xinjiang by Western journalists, and it has sought to silence criticism from Uyghurs overseas by threatening to punish their family members at home and deny them entry into China.

Although the State Department report focused on Beijing’s global influence efforts outside the United States, its findings are similar to those documented in the U.S. by think tanks and advocacy groups.

Testifying before the Senate Intelligence Committee last week, Sarah Cook, a senior advisor for China, Hong Kong and Taiwan at Freedom House, said Beijing’s disinformation campaign targeting the U.S. could sow discord and might influence election results at the local level, especially in districts with a large number of Chinese American voters. They are more likely to be using WeChat, a popular Chinese-language messaging app heavily controlled by Beijing, she said.

Glenn Tiffert, who co-chairs a project on China’s influence campaigns at the Hoover Institution, told the committee that the use of new technology, such as artificial intelligence, could allow Beijing to interfere more effectively in U.S. elections.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.