Children could fill labor shortages, even in bars, if these Republican lawmakers succeed

MADISON, Wis. — Lawmakers in several states are embracing legislation to let children as young as 14 work in more hazardous occupations, longer hours on school nights and in expanded roles including serving alcohol in bars and restaurants.

The efforts to significantly roll back labor rules are largely led by Republican lawmakers to address worker shortages and in some cases run afoul of federal regulations.

Child welfare advocates worry the measures represent a coordinated push to scale back hard-won protections for minors.

“The consequences are potentially disastrous,” said Reid Maki, director of the Child Labor Coalition, which advocates against exploitative labor policies. “You can’t balance a perceived labor shortage on the backs of teen workers.”

Lawmakers proposed loosening child labor laws in at least 10 states over the last two years, according to a report published last month by the pro-labor Economic Policy Institute. Some bills became law; others were withdrawn or vetoed.

Legislators in Wisconsin, Ohio and Iowa are considering relaxing child labor laws to address worker shortages, which are driving up wages and contributing to inflation. Employers have struggled to fill positions after a wave of retirements, deaths and illnesses from COVID-19, decreases in legal immigration and other factors.

Experts warn the pandemic could force millions of children worldwide out of school and into the work force, exposing them to stress and exploitation.

The job market is one of the tightest since World War II, with the unemployment rate at 3.4% — the lowest in 54 years.

Economists point to other strategies the country can employ to alleviate the labor crunch without asking kids to work more hours or in dangerous settings.

The most obvious is allowing more legal immigration, which many Republicans oppose. Other strategies could include offering incentives to older workers to delay retirement, expanding opportunities for formerly incarcerated people and making child care more affordable.

In Wisconsin, lawmakers are backing a proposal to allow 14-year-olds to serve alcohol in bars and restaurants. If passed, Wisconsin would have the lowest such limit nationwide, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

The Ohio Legislature is on track to pass a bill allowing students ages 14 and 15 to work until 9 p.m. during the school year with their parents’ permission. That’s later than federal law allows, so a companion measure asks Congress to amend it.

The moral scourge of child labor was supposedly eradicated in America more than 100 years ago. Red states are bringing it back in the name of parental rights.

Under the federal Fair Labor Standards Act, students that age can work only until 7 p.m. during the school year. Congress passed the law in 1938 to stop children from being exposed to dangerous conditions and abusive practices in mines, factories, farms and street trades.

Republican Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed a law in March eliminating permits that required employers to verify a child’s age and their parents’ consent. Without work permit requirements, companies caught violating child labor laws can more easily claim ignorance.

Sanders later signed separate legislation raising civil penalties and creating criminal penalties for violating child labor laws, but advocates worry that eliminating the permit requirement makes it significantly more difficult to investigate violations.

Other measures to loosen child labor laws have been passed into law in New Jersey, New Hampshire and Iowa.

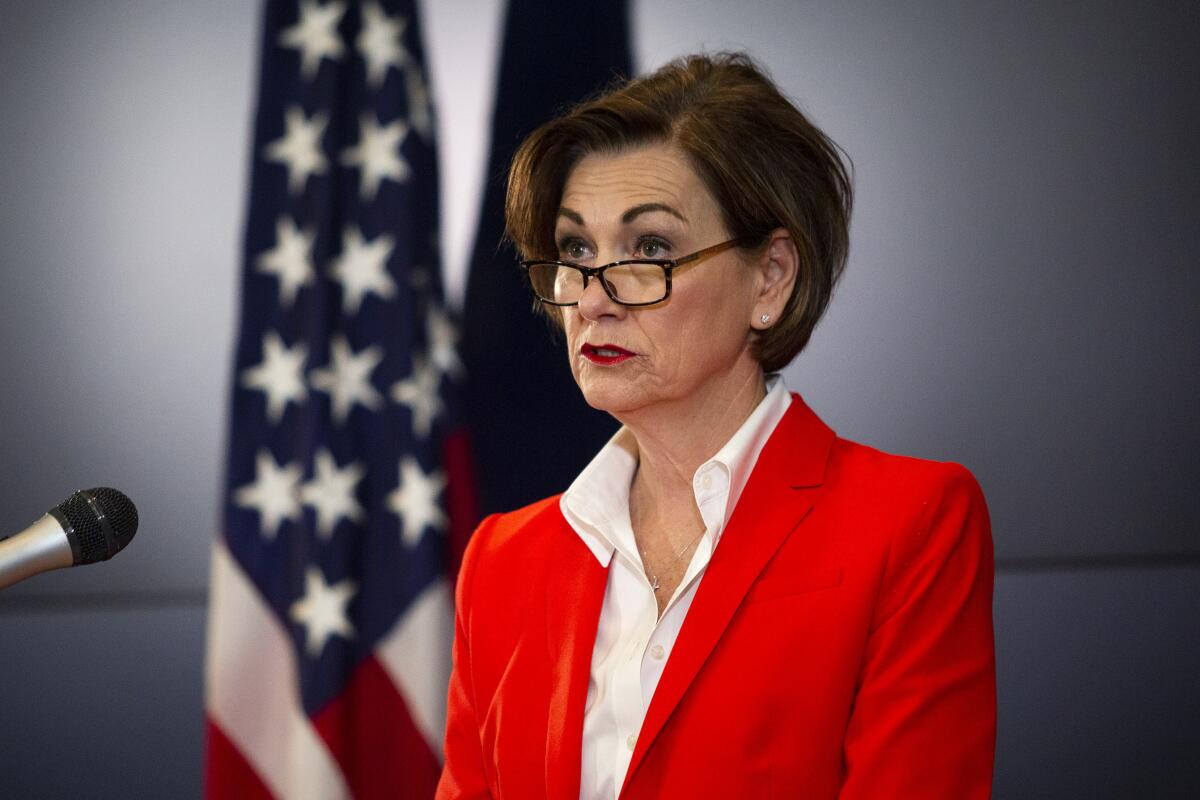

Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds signed a law last year allowing 16- and 17-year-olds to work unsupervised in child care centers. The state Legislature approved a bill this month to allow teens of that age to serve alcohol in restaurants. It would also expand the hours minors can work. Reynolds, a Republican who said in April she supports expanding child labor, has until June 3 to sign or veto the measure.

Republicans dropped provisions from a version of the bill allowing children aged 14 and 15 to work in dangerous jobs including mining, logging and meatpacking. But it kept some provisions that the Labor Department say violate federal law, including allowing children as young as 14 to briefly work in freezers and meat coolers, and extending work hours in industrial laundries and assembly lines.

Teen workers are more likely to accept low pay and less likely to unionize or push for better working conditions, said Maki of the Child Labor Coalition, a Washington-based advocacy network.

“There are employers that benefit from having kind of docile teen workers,” Maki said, adding that teens are easy targets for industries that rely on vulnerable populations such as immigrants and the formerly incarcerated to fill dangerous jobs.

The Department of Labor reported in February that child labor violations had increased by nearly 70% since 2018. The agency is increasing enforcement and asking Congress to allow larger fines against violators.

Employees at a Popeyes in Oakland went on strike after multiple teen workers alleged they worked long, late hours in violation of labor laws. Officials for the fast food chain closed the franchise, promising an investigation.

It fined one of the nation’s largest meatpacking sanitation contractors $1.5 million in February after investigators found the company illegally employed more than 100 children at locations in eight states. The child workers cleaned bone saws and other dangerous equipment in meatpacking plants, often using hazardous chemicals.

National business lobbyists, chambers of commerce and well-funded conservative groups are backing the state bills to increase teen participation in the workforce, including Americans for Prosperity, a conservative political network, and the National Federation of Independent Business, which typically aligns with Republicans.

The conservative Opportunity Solutions Project and its parent organization, Florida-based think tank Foundation for Government Accountability, helped lawmakers in Arkansas and Missouri draft bills to roll back child labor protections, the Washington Post reported. The groups, and allied lawmakers, often say their efforts are about expanding parental rights and giving teenagers more work experience.

Two 10-year-olds are among 300 children who worked at McDonald’s restaurants in Kentucky illegally, a Labor Department investigation found.

“There’s no reason why anyone should have to get the government’s permission to get a job,” Republican Arkansas Rep. Rebecca Burkes, who sponsored the bill to eliminate child work permits, said on the House floor. “This is simply about eliminating the bureaucracy that is required and taking away the parents’ decision about whether their child can work.”

Margaret Wurth, a children’s rights researcher with Human Rights Watch, a member of the Child Labor Coalition, described bills like the one passed in Arkansas as “attempts to undermine safe and important workplace protections and to reduce workers’ power.”

Current laws fail to protect many child workers, Wurth said.

She wants lawmakers to end exceptions for child labor in agriculture. Federal law allows children 12 and older to work on farms for any amount of time outside of school hours, with parental permission. Farmworkers older than 16 can work at dangerous heights or operate heavy machinery, hazardous tasks reserved for adult workers in other industries.

Twenty-four children died from work injuries in 2021, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. About half of deadly work incidents happened on farms, according to a report from the Government Accountability Office covering child deaths between 2003 and 2016.

“More children die working in agriculture than in any other sector,” Wurth said. “Enforcement isn’t going to help much for child farmworkers unless the standards improve.”

Harm Venhuizen is a corps member for the Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues. Follow Venhuizen on Twitter.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.