MEXICO CITY — The deadly fire at a migrant detention center in northern Mexico last week has put a spotlight on why, amid harsh U.S. immigration policies, migrants continue to make the dangerous journey north.

What makes conditions at home so untenable that they outweigh the hostilities of the migrant trail or the chance of being turned back at the border?

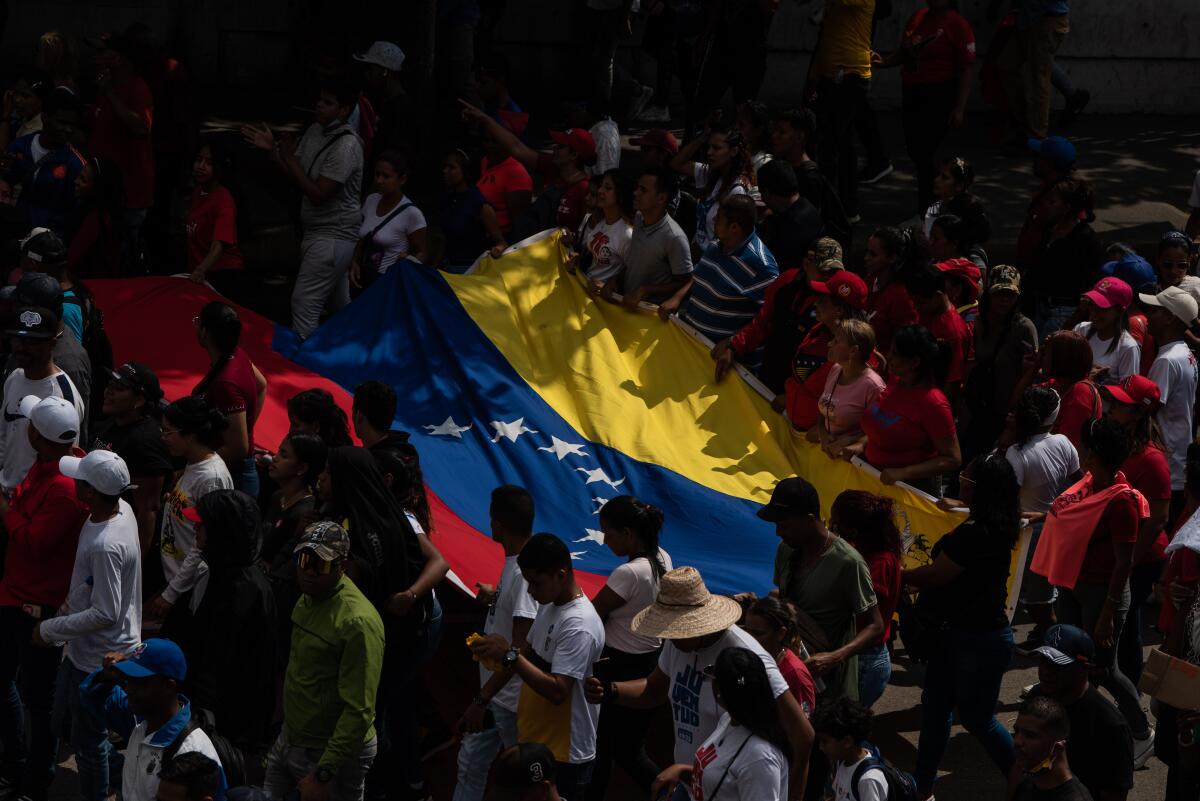

The 39 men killed and dozens wounded in the Ciudad Juarez blaze came from Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Venezuela and Colombia — countries beset by political instability, poverty or violence.

Those conditions, as well as natural disasters, or inequality worsened by the pandemic, are driving people north. Pandemic travel restrictions had limited migration, but the number of travelers increased again in 2021 as the constraints started to lift.

Mexico, which accounts for the highest number of border crossings, has agreed to accept those turned out of the U.S. under Title 42, a public health policy that allows agents to quickly expel asylum seekers and block access to the U.S.

Asylum seekers now wait in packed shelters for Title 42 to lift in May or for appointments with border officials — made through an overloaded mobile app — in the hopes that they’ll qualify for a humanitarian exemption to the health policy.

But officials and advocates contend that Mexico is not equipped to handle the influx of people stranded there. They are bracing for this summer when the U.S. is expected to roll out a new policy that will limit asylum access for migrants who crossed into the U.S. without authorization and didn’t apply for protections on the way.

In border cities such as Ciudad Juarez, shelter directors are already struggling to expand their bed space, and human rights groups have decried arbitrary detentions of migrants by police.

Here are the countries, apart from Mexico, whose citizens account for the highest number of encounters between U.S. border officials and migrants who attempted to cross in January and February, and the factors leading people to flee northward.