Autism is now more common among Black and Latino kids in the U.S.

NEW YORK — For the first time, autism is being diagnosed more frequently in Black and Latino children than in white kids in the U.S., the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Thursday.

Among all U.S. 8-year-olds, 1 in 36 had autism in 2020, the CDC estimated. That’s up from 1 in 44 two years earlier.

But the rate rose faster for children of color than for white kids. The new estimates suggest that about 3% of Black, Hispanic or Latino and Asian or Pacific Islander children have been diagnosed with autism, compared with about 2% of white kids.

That’s a contrast to the past, when autism was most commonly diagnosed in white kids — usually in middle- or upper-income families with the means to go to autism specialists. As recently as 2010, white kids were deemed 30% more likely to be diagnosed with autism than Black children and 50% more likely than Latino children.

Experts attributed the change to improved screening and autism services for all kids, and to increased awareness and advocacy for Black and Latino families.

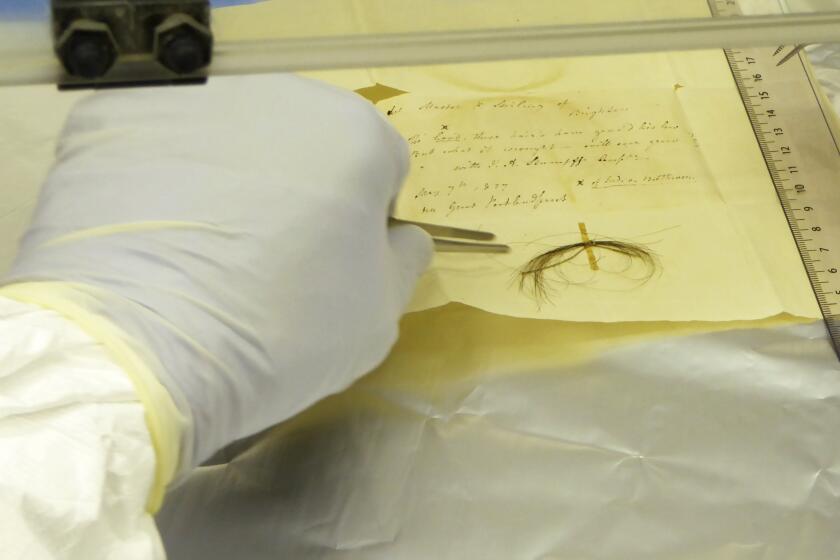

Hundreds of years after Beethoven’s death, researchers using DNA from strands of his hair have found clues about what killed him, according to a new study.

The increase is from “this rush to catch up,” said David Mandell, a University of Pennsylvania psychiatry professor.

Still, it’s not clear that Black and Latino children with autism are being helped as much as their white counterparts. A study published in January found that Black and Latino kids had less access to autism services than white children during the 2017-2018 academic year.

Autism is a developmental disability caused by differences in the brain. There are many possible symptoms, many of which overlap with other diagnoses. They can include delays in language and learning, social and emotional withdrawal, and an unusual need for routine.

Scientists believe genetics can play a role, but there is no known biological reason why it would be more common in one racial or ethnic group than another.

For decades, the diagnosis was given only to kids with severe problems communicating or socializing and those with unusual and repetitive behaviors. But around 30 years ago, the term became shorthand for a group of milder related conditions known as ″autism spectrum disorders.”

In order to move through a world where the coronavirus is endemic, we need a reliable way to assess our individual level of immunity. Here’s how we can.

There are no blood or biological tests for it; it’s diagnosed by observing and analyzing a child’s behavior.

To estimate how common autism is, the CDC checks health and school records in 11 states and focuses on 8-year-olds, because most cases are diagnosed by that age. Other researchers have their own estimates, but the CDC’s estimate is widely considered by experts to be the gold standard.

The overall autism rate has been rising for decades. It remains far more common among boys than girls, but the latest study also found, for the first time, that more than 1% of 8-year-old girls had been diagnosed with it.

A second CDC report issued Thursday looked at how common autism was in 4-year-olds. That research is important because diagnoses are increasingly happening at younger ages, said Kelly Shaw, who oversees the CDC’s autism tracking project.

Black children with autism have historically been diagnosed at later ages than their white peers, said Rose Donohue, a psychiatrist at Washington University. But the study found that autism diagnoses by age 4 were less common in white kids in 2020 than among Black, Latino and Asian and Pacific Islander children.

However, children were less likely in 2020 to have been evaluated for autism by age 4 than kids were in the past. Shaw said that was likely due to interruptions in child care and medical services during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.