Wyoming Democrats get trounced again, but persevere

CHEYENNE, Wyo. — Aaron Appelhans is among a rare few in Wyoming: a Democrat who won in Tuesday’s midterm election in this ever-redder state.

Appointed as the state’s first Black sheriff last year, he is now its first elected Black sheriff. He beat a 20-year Republican police veteran with 52% of the vote.

“Albany County’s kind of purple politically, so I was able to run on my record, the things that I’ve done,” Appelhans said Thursday.

But Wyoming Democrats overall suffered another dismal election, even as their party defied expectations and did reasonably well nationwide.

Democrats didn’t even field candidates for three of Wyoming’s six statewide races — those for secretary of state, treasurer and auditor. They won just 25%, 17% and 23% of the vote in the other three — the contests for U.S. House, governor and superintendent of public instruction, respectively.

The party will keep its two seats in the 31-member state Senate. But Democrats lost two of their seven seats in the 62-member state House, pushing their share of the Legislature under 8%.

Wyoming had a centrist Democratic governor, Dave Freudenthal, from 2003 to 2011. But in a state where many cherish gun ownership, are often suspicious of LGBTQ advocacy and stand up for the coal mining industry amid efforts to limit climate change, the party has been on the decline since the 1990s.

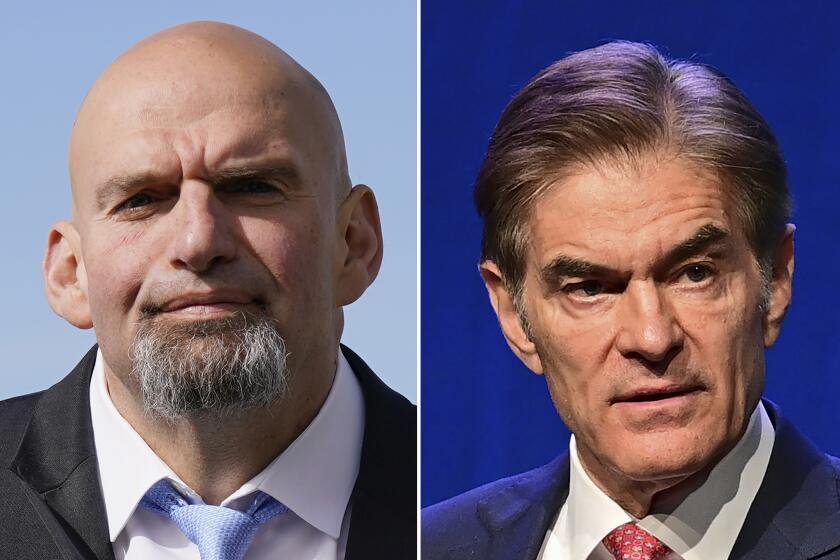

John Fetterman, who campaigned after suffering a stroke, defeats Trump-endorsed Mehmet Oz in a Senate race marked by attacks and trolling.

“We’ve had election cycle after election cycle now, dating back to 1994, when Republicans have been very effective at characterizing any Wyoming Democrat as representing the national party,” said University of Wyoming political science professor Jim King.

“Whether they do doesn’t really matter,” he said. “In these low-information races, the charge sticks, and Democrats then find themselves at a disadvantage on election night.”

But even in a state that gave Donald Trump 70% of the vote in 2020, some Democrats say they can win by talking to as many voters one-on-one as possible.

Appelhans credits on-the-ground campaigning, good organization and hard work by volunteers — along with policing reforms he has implemented in the Sheriff’s Office — for his win in southeastern Wyoming’s Albany County, home to the University of Wyoming.

“It took a lot of time. I worked two jobs,” Appelhans said of his campaign. “We had a good crew — a large, large group of volunteers, people that, you know, are believers in my abilities, believers in the campaign — to go out there and help as well. It really was kind of a community effort.”

Another winning Democrat was Pete Gosar, a former state party chairman who was reelected to the Albany County Commission. He received the most votes in a four-way race for two commission seats up for grabs.

A brother of Republican U.S. Rep. Paul Gosar of Arizona, he rejected any notion that most voters, at least in Albany County, are hyperpartisan once you get to know them personally.

“It’s not just luck. There’s a real strategy to get out and meet people,” Pete Gosar said. “You hear about hyper-partisanship, and you’d expect that in the state that voted for the former president by the widest margin. But that’s not what I found, whether it was Republican, Democratic or independent doors. They might not vote for you, but there was kindness and cordiality.”

Decades ago, Democrats could rely on Albany County and the rest of southern Wyoming, with its many union railroad and coal mining jobs, as reliable turf.

In Georgia, Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock and his Republican challenger, Herschel Walker, are headed for a Senate runoff election.

But that hasn’t been the case for a long time. Along with Albany County, only Teton County, at the doorstep of Grand Teton and Yellowstone national parks, has an electorate that isn’t overwhelmingly Republican.

Wyoming’s losing Democrats this year included the chairman of the state party, Joe Barbuto, who with 31% of the vote failed to win reelection as Sweetwater County treasurer. Barbuto didn’t immediately return phone and social media messages Thursday seeking comment.

Another was Chad Banks, whose state House district lies within southwestern Wyoming’s Sweetwater County. A gay former Rock Springs City Council member who was first elected to the state House in 2020, Banks got 39% of the vote in losing to a local Republican businessman.

Banks voted with Republicans 90% or more of the time in the Legislature, he said, but getting associated with issues pushed by Democrats nationally cost him and other Democrats in the state.

“I still support our coal communities in Wyoming. I hope that coal remains a strong industry in Wyoming. It’s important to my community and it’s important to my state — and that’s of course different than what you’re hearing from the D.C. crowd,” Banks said.

For Gosar at least, the key for Wyoming Democrats to counter the party’s perspective nationally is to bring a Wyoming-focused message to as many people as possible locally.

”It’s easy to, you know, sing the death song for the Wyoming Democratic Party, and things are difficult,” Gosar said.

“But I think there’s real opportunity, and I think it all starts with some of the stuff that’s been done in Albany County,” he said. “You have to get out and talk to people and give them a different perspective.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.