Haiti gang makes demands in test of power with government

SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico — A standoff between a powerful gang federation and Haiti’s government is testing how much power both sides wield and threatens to further derail a paralyzed country where millions of people are struggling to find fuel and water.

A former police officer who leads a gang alliance known as G9 and Family has proposed his own plan for Haiti’s future — even seeking seats in the Cabinet — while demanding that the administration of Prime Minister Ariel Henry grant amnesty and void arrest warrants against the group’s members, a demand that so far has gone unanswered.

In mid-September, the gang surrounded a key fuel terminal to demand Henry’s resignation and to protest a spike in petroleum prices after the prime minister announced that his administration could no longer afford to subsidize fuel.

That move, coupled with thousands of protesters who have blocked streets in the capital of Port-au-Prince and other major cities, has caused major shortages, forcing hospitals to cut back on services, gas stations to close and banks and grocery stores to restrict hours.

In a recent video posted on Facebook, G9 and Family leader Jimmy Cherizier, who goes by the nickname Barbecue, read a proposed plan to stabilize Haiti that includes the creation of a “Council of Sages” with one representative from each of Haiti’s 10 departments.

The gang also is demanding positions in Henry’s Cabinet, according to the director of Haiti’s National Disarmament, Dismantling and Reintegration Commission, speaking to radio station Magik 9 on Thursday.

“It’s a symptom of their power, but also a symptom that they may fear what is coming,” Robert Fatton, a Haitian politics expert at the University of Virginia, said of the gang’s demands.

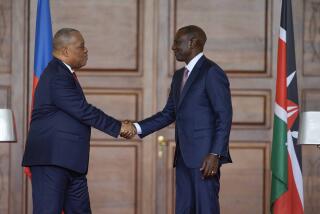

Henry and 18 members of his Cabinet appealed nearly a week ago for the deployment of foreign troops to quell violence and end the fuel blockade, a proposal that has yet to be formally discussed by the United Nations Security Council, which meets Monday.

The gang, which has overpowered an understaffed and under-resourced police department, is likely wary of the potential deployment of specialized armed troops, Fatton said.

“They are trying to get the best deal they can get while to some extent they have the upper hand,” he said.

Gang demands are nothing new in Haiti, and they have grown more powerful since the July 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse.

But such threats were quickly quelled in the past with the help of U.N. peacekeeping forces, Fatton said.

In the aftermath of a rebellion that ousted former Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, then-President Réné Préval ordered gangs to lay down their weapons. He did it peacefully at first, but upon receiving no results, he threatened them.

“They were told, ‘You either disarm, or you’re going to be dead,’” Fatton said. “Some gangs accepted the solution, and others were destroyed.”

He said special forces used drones and invaded slums, which gangs have long controlled.

But gangs have played major political roles before: The leader of one gang helped launch the revolt that removed Aristide, who refused to resign before the end of his term in 2006. That leader, Butteur Metayer, had been an Aristide supporter, but turned against him after his brother, also a gang leader, was killed in 2003.

Fatton said that while the demand to give Cherizier’s gang federation Cabinet positions is “a crazy proposition,” he added that an amnesty involving giving up weapons might be a solution.

“The government saves face, the gangs say, ‘We’ve achieved what we’ve wanted,’ and there’s a compromise,” he said.

But the demand to void arrest warrants would likely be rejected by the government, which has long sought to arrest Cherizier on charges including orchestrating one of the country’s worse massacres, in which dozens of men, women and children were slain.

Haitian officials have warned the international community that the situation is dire, noting that a recent cholera outbreak could also worsen due to the limited availability of water and other basic supplies.

On Friday, UNICEF warned that nearly 100,000 children younger than 5 are already suffering from severe acute malnutrition and are vulnerable to cholera: “The crisis in Haiti is increasingly a children’s crisis.”

It is also becoming a crisis for women. The United Nations Population Fund said Friday that 30,000 pregnant women are at risk because roughly three-fourths of Haiti’s hospitals are unable to provide services due to a lack of fuel.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.