2 Californians among trio who share Nobel Prize in chemistry for devising ‘molecular Lego’

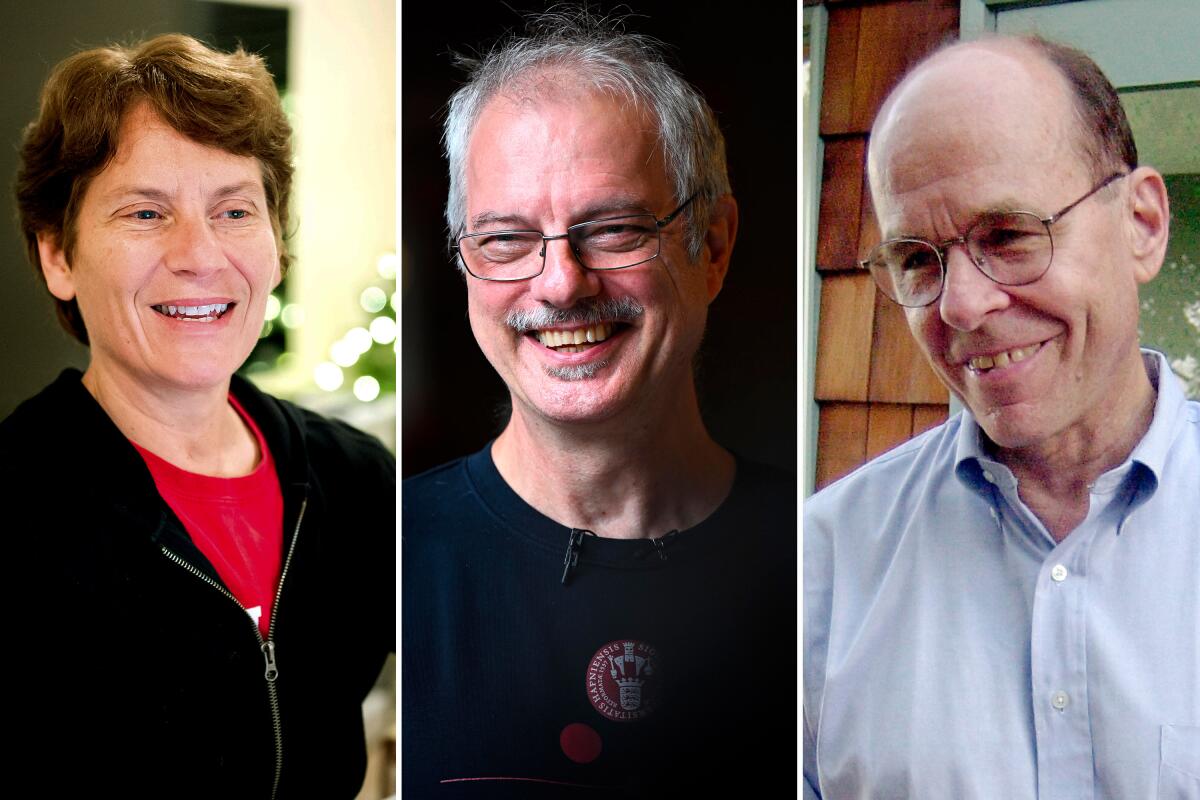

STOCKHOLM — Two California scientists and a third from Denmark won the Nobel Prize in chemistry Wednesday for developing a way of “snapping molecules together” that can be used to explore cells, map DNA and design drugs that target diseases such as cancer more precisely.

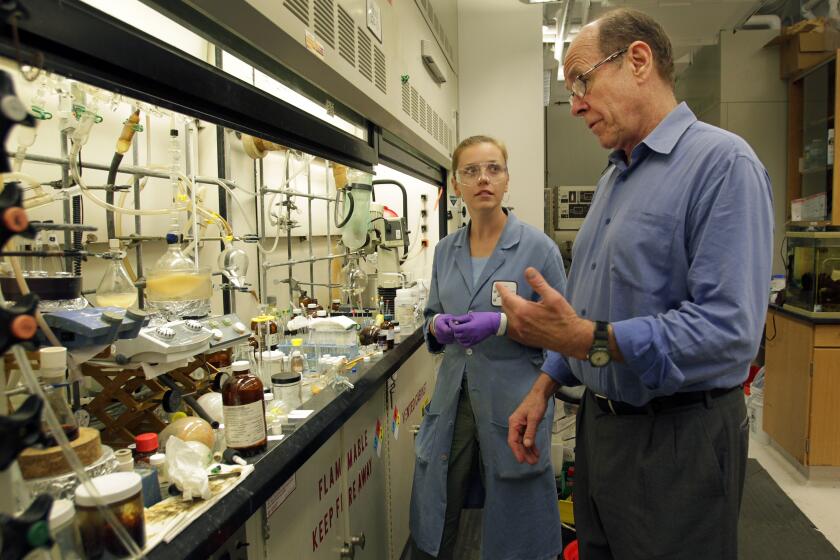

Carolyn R. Bertozzi of Stanford University, K. Barry Sharpless of Scripps Research in La Jolla and Morten Meldal of the University of Copenhagen were cited for their work on “click chemistry” and bioorthogonal reactions.

“It’s all about snapping molecules together,” said Johan Aqvist, a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which announced the winners at a news conference in Stockholm.

Sharpless, who previously won a Nobel Prize in 2001 and is now the fifth person to receive the award twice, first proposed the idea around the turn of the millennium. He was looking for a faster and simpler way to create molecules without producing unwanted products that had to be carefully removed. His solution was

a streamlined process for connecting simple molecules together using chemical “buckles,” Aqvist said.

“The problem was to find good chemical buckles,” he said. “They have to react with each other easily and specifically.”

News Alerts

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Sharpless, 81, and Meldal, 68, independently found the first such candidates that would easily snap together with each other but not with other molecules, leading to applications in the manufacture of medicines and polymers.

Bertozzi, 55, “took click chemistry to a new level,” the Nobel panel said, by finding a way to make the process work inside living organisms without disrupting them.

The goal is “doing chemistry inside human patients to make sure that drugs go to the right place and stay away from the wrong place,” she said at a news conference following the announcement.

The researchers win the Nobel Prize in physics for work on quantum mechanics with significant applications in the field of encryption and other areas.

The award was a shock, she said. “I’m still not entirely positive that it’s real, but it’s getting realer by the minute.”

She added that “the attention that a prize like the Nobel Prize brings can be incredibly energizing for a scientific field.”

In an interview, Bertozzi said one of the first people she called after being awakened by the call around 2 a.m. was her father, William Bertozzi, a retired physicist and night owl, who was still awake watching TV.

“‘Dad, turn down the TV, I have something to tell you,’” she said she told him. After assuring him nothing was wrong, he guessed the news. “You won it, didn’t you?” he said.

One of three daughters, Bertozzi said she was “fortunate because I grew up with parents that were very supportive, evangelical almost, about having their girls participate in the sciences.”

For 3.7 billion years, nature has used the power of evolution to shape every living thing on Earth, creating a vast diversity of molecules with an ever-increasing array of abilities.

Meldal said he received a call from the Nobel panel about half an hour before the public announcement.

“They ... told me not to tell anyone,” he said, adding that he just sat in his office, shaking a bit. “This is a huge honor.”

Meldal started out as an engineer, “but I wanted to understand the world, so I thought chemistry would give me the solutions,” he said.

Sharpless, a reclusive figure who wasn’t available for comment Wednesday, initially planned to go to medical school. That changed after taking organic chemistry as a college sophomore and conducting research.

“His work opened whole new scientific frontiers that have had a major impact on the fields of chemistry, biology and medicine,” said Peter Schultz, president of Scripps Research. “Barry has a remarkable combination of chemical insight, uncanny intuition, and real-world practicality — he is a chemist’s chemist and a wonderful colleague.”

At least 27 scientists with San Diego ties have won Nobel Prizes. Is there something in the water?

Jon Lorsch, director of the U.S. National Institute of General Medical Sciences, which supports the work of Bertozzi and Sharpless, described click chemistry and bioorthogonal chemistry as “sort of like molecular Lego — you have a group on one molecule that specifically attaches to a group on another molecule,” like Lego pieces clicking together.

“That makes it possible to attach molecules in very specific predefined ways,” he said, and gives scientists a very precise tool to build complex new molecules that can be used for drugs, synthetic materials and other uses.

But the first iteration of click chemistry could not be used to work on living cells.

“The original click chemistry used copper as a catalyst to join molecules,” Lorsch said. “But the trouble is that copper is toxic to most living systems at higher concentrations.”

Bertozzi devised a way to jump-start the reactions without copper or other toxic solvents, broadening the applications of the molecular Lego to human and animal tissues.

“Being able to work without dangerous solvents opened many new doors — it enabled scientists to work on new types of reactions that actually take place within the human body,” said Angela Wilson, president of the American Chemical Society.

For example, it has allowed scientists to attach dyes to cancer cells to track their movements and analyze how they differ from healthy tissue.

The Nobel Prize in chemistry is awarded to Jennifer Doudna of UC Berkeley and Emmanuelle Charpentier for their work on the CRISPR gene-editing tool.

Wilson, who is also a professor at Michigan State University, said she believes the advances of this year’s Nobel laureates “will allow more individualized medicine in the future because we can really track things much better within the human body.”

M.G. Finn, a chemist now at Georgia Tech who collaborated with Sharpless on his Nobel-winning work, said click chemistry’s use in biology and drug development was still “at its infancy,” with more exciting discoveries to come.

Meldal agreed.

Winning the Nobel is “very much an opportunity ... to argue for our young people to take chemistry as a discipline at the university,” he said at a news conference in Copenhagen. “Chemistry is the solution to many of our challenges.”

Wednesday’s news reflects California’s continuing dominance in the field. Over the last 20 years, 13 Californians have shared the Nobel in chemistry.

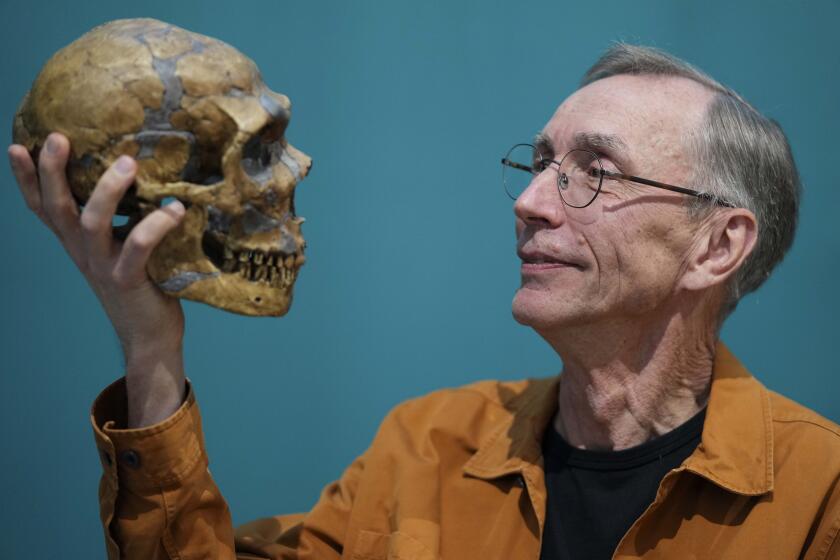

Svante Paabo’s discoveries on human evolution provided key insights into our immune system and what makes us unique compared with our extinct cousins.

A week of Nobel Prize announcements kicked off Monday with Swedish scientist Svante Paabo receiving the award in medicine for unlocking secrets of Neanderthal DNA that provided key insights into our immune system.

Three scientists, including a Californian, jointly won the prize in physics Tuesday. American John F. Clauser of Walnut Creek, Frenchman Alain Aspect and Austrian Anton Zeilinger had shown that tiny particles can retain a connection with one another even when separated, a phenomenon known as quantum entanglement that can be used for specialized computing and to encrypt information.

The awards continue with literature Thursday. The 2022 Nobel Peace Prize will be announced Friday and the economics award Monday.

The prizes carry a cash award of 10 million Swedish kronor — nearly $900,000 — and will be handed out Dec. 10. The money comes from a bequest left by the prize’s creator, Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel, who died in 1896.

Keyton and Jordans reported from Stockholm and Larson from Washington. AP writers Jan M. Olsen in Copenhagen and Maddie Burakoff in New York contributed to this report, as did Gary Robbins of the San Diego Union-Tribune.