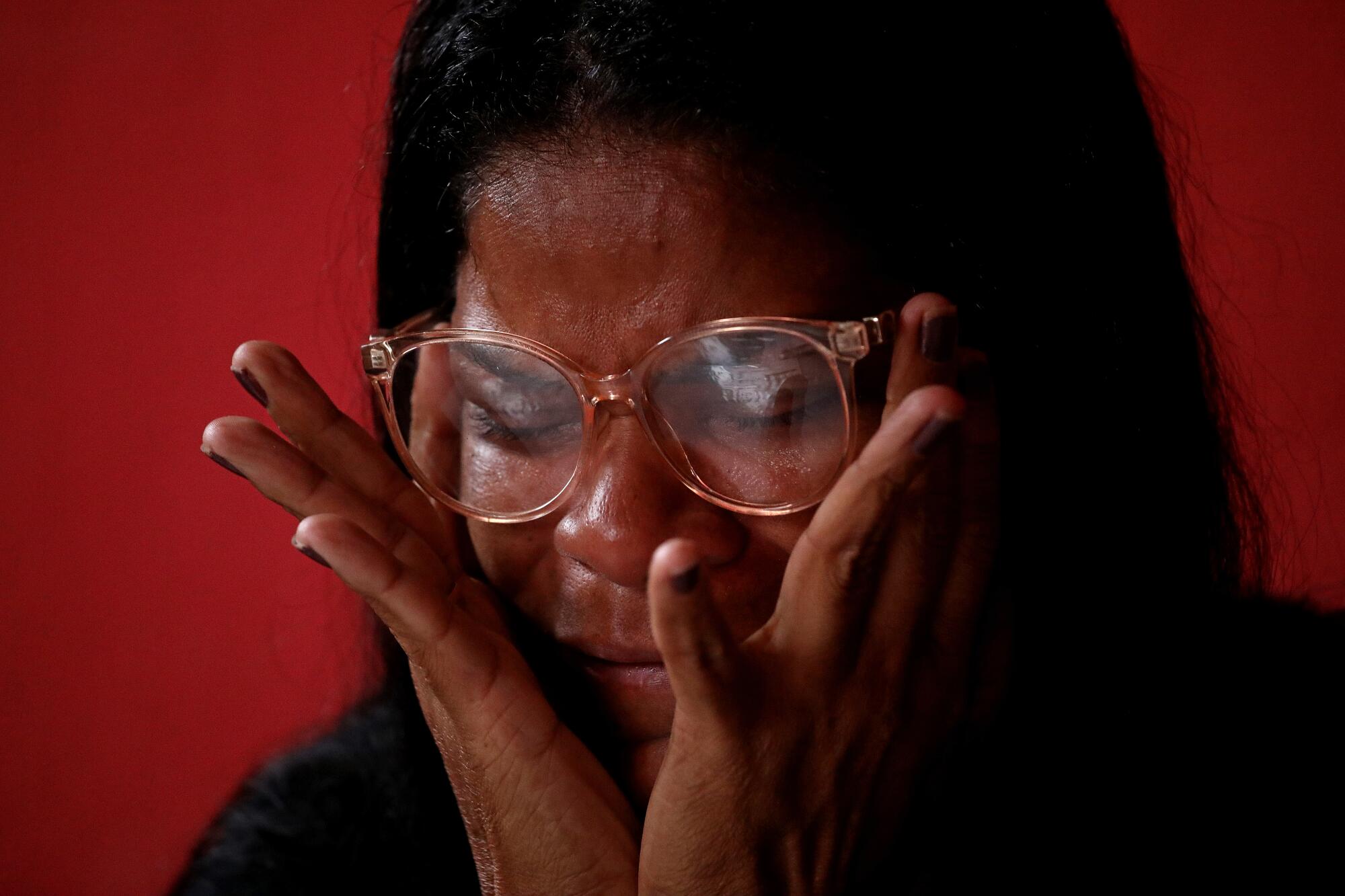

RIO DE JANEIRO — On the day she was to face her son’s killers, Glaucia dos Santos rose early, smoothed her hair into a ponytail and donned a T-shirt emblazoned with a single word: “Gratitude.”

It may have seemed like a surprising choice given what she was about to do: travel three hours by bus from her home on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro to a downtown courthouse, where the two police officers who had gunned down her 17-year-old in 2014 were being tried for murder.

But she felt lucky.

In Brazil, where even the most egregious abuses by police are rarely punished, trials like this one were practically unheard of. Against all odds, and thanks only to her own dogged detective work, Dos Santos now had a shot at justice.

Her eight-year battle for a day in court had come amid a surge of killings by police that had made Brazil’s law enforcement agencies among the world’s most lethal.

Police killed 6,145 people here last year, according to the nonprofit Brazilian Forum on Public Safety — an average of almost 17 a day and nearly triple the 2013 total.

Taking population size into account, officers killed at roughly nine times the rate of U.S. law enforcement.

In Rio de Janeiro state, killings by police accounted for nearly a third of all homicides. Most took place in favelas, former squatter settlements founded by ex-slaves that remain predominantly Black today and have few state services and a heavy gang presence.

The rise in police violence has been celebrated by President Jair Bolsonaro, who has pushed for laws that would provide immunity for officers who commit homicide in the line of duty and declared that “a policeman who doesn’t kill isn’t a policeman.”

His challenger in Sunday’s presidential election, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has said little about the issue, with some political observers concluding that he is wary of conflict with the police because of the possibility that they could back Bolsonaro in an attempt to steal the election. Still, if Lula, as he is known, becomes president, as polls suggest he will, he will face pressure from segments of his base who have become increasingly vocal about the need for police reform.

Though officers almost always defend their killings as acts of self-defense against armed criminals, human rights groups and journalists have documented a pattern of excessive use of force, including summary executions of people who are unarmed or injured.

A report by the United Nations this year said Brazil’s security strategy demonstrates an “unconscionable disregard for human life,” and highlighted a deep racial disparity. Black people make up 55% of Brazil’s population, but 84% of the people police killed last year.

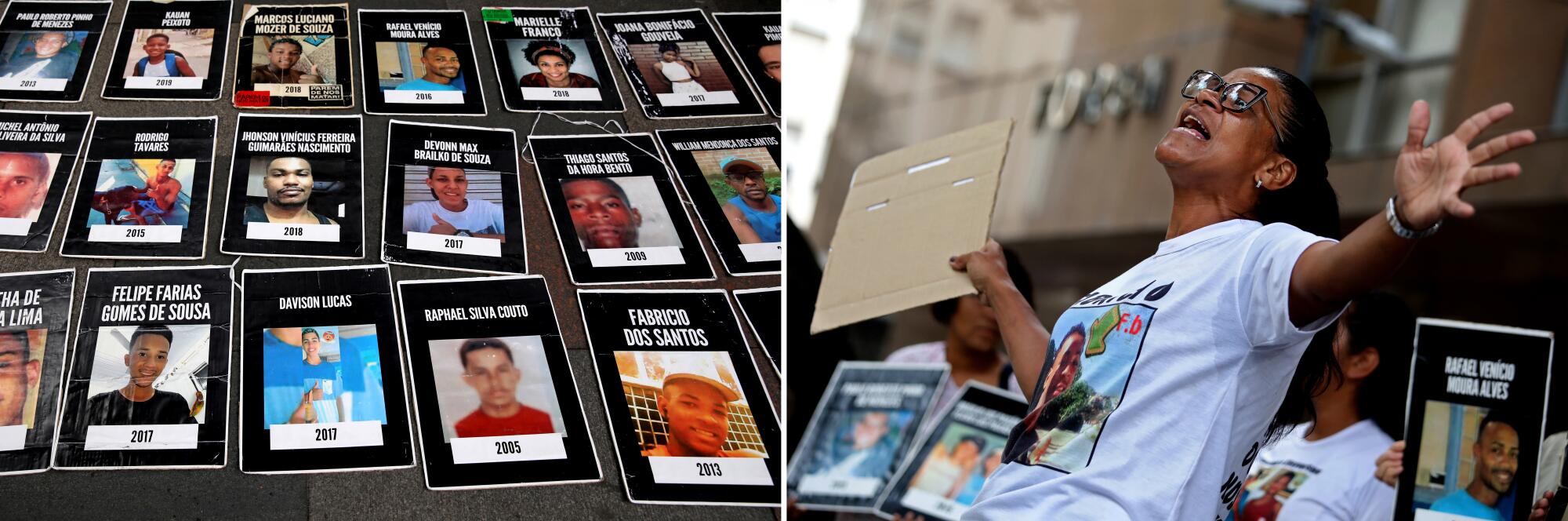

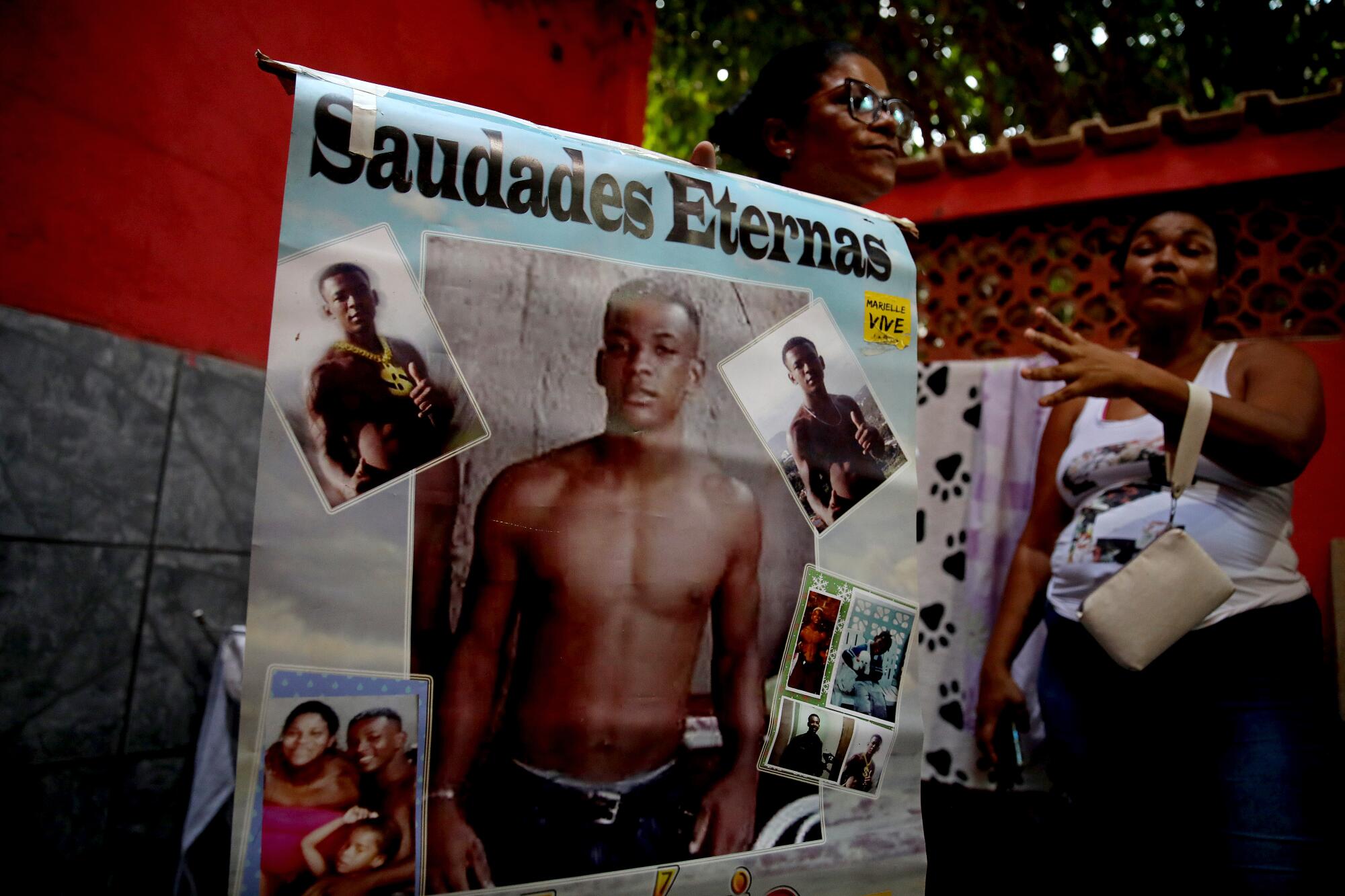

When Dos Santos, who is Black, lost her only son, Fabricio, she was thrust into a new role in her community. Each time another young man died, his mother would come to her for comfort and advice. As the years wore on, a WhatsApp group of grieving mothers that she had created came to include about a dozen neighbors and even her own sister.

At the courthouse last month, Dos Santos, 46, was accompanied by several of them, each clutching a photograph of their own dead child. For many, Fabricio’s case had become deeply personal because they knew they were unlikely to ever get their own day in court.

A raid of a Rio de Janeiro shantytown that killed at least 18 people has ignited debate over how to handle crime ahead of a presidential election.

Sun streaked through the clouds as the women stood shoulder to shoulder chanting Fabricio’s name and the thing they all wanted: “Justiça.”

“The police are supposed to protect,” Dos Santos told a crowd of people who had stopped to watch the impromptu protest, her voice trembling. “We want you to stop killing us.”

Then she and the rest of the women filed into the courthouse.

Dos Santos knew it was never going to be easy raising a son in the favela.

Her community, Chapadão, is a labyrinth of small homes made of unpainted brick and corrugated tin roofs stretching across hillsides on the far north side of Rio.

Fabricio’s father, a former soldier, left when he was a baby, and his mother worked as a housekeeper. When Fabricio was 3, he was hit by a truck speeding through the neighborhood, leaving him with a permanent limp.

For her shy son, who dreamed of being a mechanical engineer, life’s biggest preoccupation wasn’t the cruel taunts of classmates or even the gangs who peddled drugs in the streets. It was the police.

Officers hassled him at a local arcade and at a bus stop on his way to a job painting houses in Copacabana. Once he was hauled into a police station for riding in a car the police said had been stolen, until they changed their story and let him go.

His mother counseled him and his two younger sisters to always keep their cool when police were involved: “Never talk back to them. Don’t let yourself react.”

But Fabricio was terrified of the cops, who had a reputation for brutality in the favelas dating back to the 1970s, when the government launched a war on drugs and started going after the gangs that had formed in Brazil’s prisons and were now entrenched in many poor neighborhoods.

There have been short-lived attempts at police reform, including the introduction of community policing units in some favelas in the few years leading up to the 2014 World Cup in Rio.

Though those efforts reduced killings by police for several years, the special units never arrived in Chapadão, and eventually they were abandoned altogether. The killings started to climb again — it was not uncommon for 20 people to die in a single afternoon when police raided their favela.

By law, police can use lethal force only to confront an “imminent threat.”

“But in the streets, the law is different,” said Daniel Lozoya, a public defender in Rio de Janeiro. “He’s Black, he’s poor, so the police shoot.”

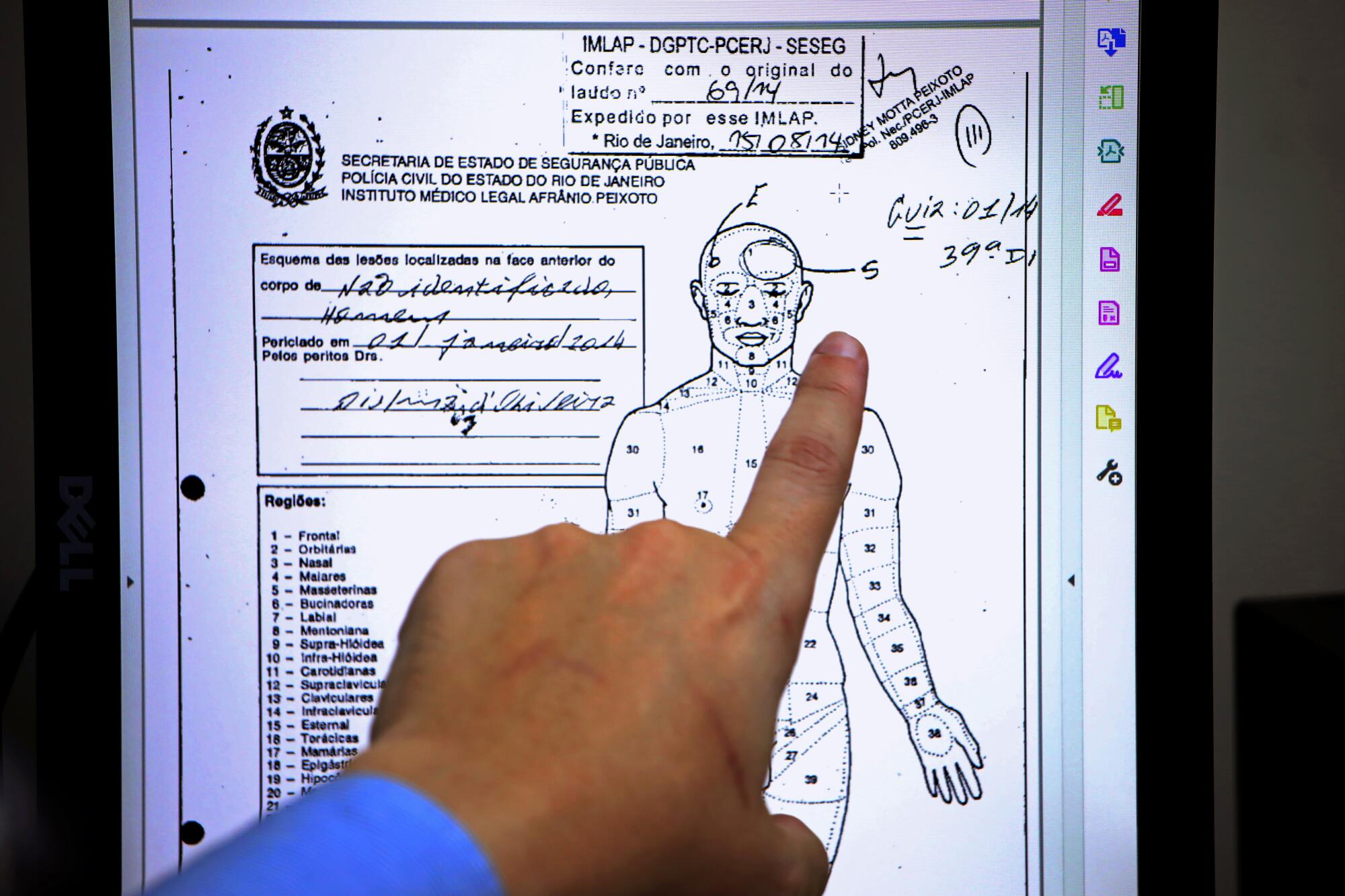

As dawn broke on Jan. 1, 2014, two police officers sat down with a police investigator to explain how and why they had just killed a young man. It was the protocol any time an officer used lethal force.

The cops, Victor Declie de Souza, who is white and was 31 at the time, and Paulo Renato do Nascimento Pires, who is Black and was 38, said they had been patrolling near Chapadão a little before 3 a.m. when three men on two motorcycles started firing at them.

The police said they chased the assailants about a mile to a gas station, where Declie used a rifle to shoot one driver as the other alleged attackers sped away.

The officers said they found a Glock pistol next to the body of the person they shot, who would later be identified as Fabricio dos Santos. They said he was still alive when they loaded his body into their car to take him to the hospital, where he was later pronounced dead.

Investigators did not visit the crime scene because the neighborhood was “too dangerous,” according to records. No forensic analysis was conducted to show whether Fabricio had ever fired the gun. Police never sought witnesses to interview.

The case could have ended there, like the vast majority of incidents in which police kill civilians here.

The attorney general’s office in Rio de Janeiro state said it does not track how many cases are brought against police officers. But multiple independent studies have shown that charges are filed in fewer than 1% of killings by police.

Marfan Martins Vieira, a former attorney general, told human rights investigators that he believes that many of the alleged shootouts between cops and civilians are “simulated” — meaning that only the police fired — but that poor-quality investigations leave prosecutors without enough information to prove it.

Cesar Muñoz, a researcher with Human Rights Watch, said prosecutors have the legal authority to investigate police abuse — and must.

“The police are not capable of investigating themselves,” he said.

Dos Santos thought the police were lying. Her son, she told investigators, had never held a gun in his life. And she had seen him head to the gas station alone, after celebrating the new year with his girlfriend. Besides, she and her neighbors hadn’t heard a shootout, just a single shot.

She was three months pregnant and battling morning sickness, but she was determined to get to the truth. “It was the least I could do for him,” she said.

After identifying Fabricio’s body, she went to the gas station, where she found employees who had been there during the killing. They shared evidence that would separate Fabricio’s case from the many others in which it is the word of a witness against the word of police: surveillance footage.

The grainy video shows Fabricio filling up his tank, putting air in his tires and preparing to exit the gas station when a police cruiser pulls up. Fabricio turns his motorcycle around and begins driving away from the cruiser. His mother thinks he probably turned because he didn’t have a driver’s license, and didn’t want trouble.

The cruiser follows him, and then, with Fabricio off screen but the vehicle still in the frame, there is a flash of light — a single shot from a rifle.

It was still January when Dos Santos took the video to the media. Soon, news crews were filming the small protests she organized in her neighborhood.

Under growing pressure, prosecutors announced that June that they were charging the two officers with murder, accusing them of fabricating the story of the shootout and planting the gun on Fabricio.

“This is very rare, that an officer actually has to answer for his actions in court.”

— Maria Julia Miranda, public defender

The officers were allowed to keep working, although they were assigned administrative tasks.

Dos Santos knew she had a long road ahead. In Brazil it can take as long as a decade for a murder case to wind its way through court.

Every few months she trekked downtown for another hearing. Years passed before a judge decided that the case deserved to go before a jury. It took months more for another judge to weigh the defendants’ appeal to that decision.

As she exited the courthouse one day in 2016, Dos Santos noticed a group of women protesting on the sidewalk. One of them was talking about her 19-year-old, whom the police had killed with a shot in the back.

For Dos Santos, joining the city’s burgeoning movement of mothers who had lost children to police bullets was like finding family.

Elsewhere, police violence was starting to receive major attention. In 2014, protesters had taken to the streets of Ferguson, Mo., after the police killing of a Black 18-year-old named Michael Brown. A hashtag was spreading on the internet: #BlackLivesMatter.

In Brazil, the movement was growing, but more slowly.

Though slavery lasted here until 1888, longer than anywhere else in the Americas, Brazil never had formal segregation like in the United States, and the country had long viewed its history more through the lens of class than race.

Among the key figures in the burgeoning antiracism movement was Rio de Janeiro City Councilwoman Marielle Franco. A single mother from a favela not far from Chapadão, she was passionate about stopping abuse by police, whom she accused of acting like death squads.

In March 2018, she tweeted about a killing in a favela: “They come to carve up the population! They come to kill our young!” A few days later, she and her driver were shot to death in downtown Rio.

The two men charged with her murder are former Rio police officers. They are still awaiting trial.

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s comeback attests to concerns about inequality that have helped bring a new wave of leftists to power across Latin America.

Franco’s death intensified calls for reform. But the movement also sparked backlash.

Some argued that there couldn’t be a racial element to the killings, given that about 45% of Brazil’s police are Black. Others said tough policing was necessary, given Brazil’s battle against violent crime.

Still, killings by police were climbing far faster than homicides overall. And as homicides started to dip from their 2017 peak of 64,078, law enforcement kept killing in increasing numbers.

The trend was most extreme in Rio, where the police found an ally in Bolsonaro, who was a congressman at the time.

His pledge to crush criminals with an iron fist helped win him a national following and propel him to the presidency.

Shortly after taking office in 2019, Bolsonaro pushed legislation to shield security forces who shoot from prosecution, vowing that criminals “are going to die in the streets like cockroaches ... how it should be.” The legislation failed to pass, but many worried that the president’s rhetoric encouraged police to act violently.

During his four years in office, killings by police have hovered around their all-time high.

“A policeman who doesn’t kill isn’t a policeman.”

— President Jair Bolsonaro

Dos Santos remained undeterred, despite the costs. When she felt guilty about how her focus on the case meant she had less time for her three daughters, she told herself she was doing it for them and the other children of the favela.

She also came to believe that her activism was putting her own life in danger.

One friend from the favela who had lost a son to police bullets and who had worked to get a particularly violent police officer moved out of their neighborhood faced death threats and fled.

“The police come here to hunt,” said the man, who did not give his name out of fear of retaliation. “Now I have no dignity. I have no life. I’m a fugitive.”

Dos Santos’ case had crawled along for eight years. But finally, it was a nearing a decision.

In Brazil, prosecutors and the defense lay out the details of their cases first for a judge, and then do it again before a jury in a rapid-fire trial that can reach conclusion in a single day.

A few days before the jury trial was set to begin, Dos Santos stood at the entrance to her favela waiting for the arrival of Guilherme Pimentel, the ombudsman from the Rio public defender’s office. His taxi finally pulled up, and the two embraced.

Dos Santos had spent the morning walking the neighborhood to get permission from gang leaders to let Pimentel and a small delegation of government human rights officials enter the community.

They passed a checkpoint manned by an armed guard and settled down in red plastic chairs arranged in a circle on the patio of a cafe. “We want to know what has been happening here and how we can help,” Pimentel began.

Ronaldo Lacerda, a 28-year-old funk DJ with dyed-orange hair, described the recent shooting death of his 21-year-old cousin.

“I’m lucky,” he said. “I should be dead too.”

Dos Santos was upset that Lacerda and his friends had protested the killing by setting a bus on fire.

“It’s fair to rebel. I understand,” Dos Santos said. “But you’ve got to have a strategy. One guy lights a bus on fire, and then that’s what ends up being showed on TV. They will use that image in the trial.”

The young man nodded.

Sonia Bonfim Vicente, 37, spoke next. Her husband and son were taking the son’s girlfriend to the hospital last year on a motorbike when all three were shot by police. Only the girlfriend survived.

As Bonfim talked about her son, Samuel, who was due to enlist in the military the day after he was killed, Dos Santos reached out and took her arm.

A public defender jotted down Bonfim’s information. But she cautioned the crowd against too much hope.

“She’s an exception,” the public defender, Maria Julia Miranda, said of Dos Santos. “This is very rare, that an officer actually has to answer for his actions in court.”

Inside the courthouse, Dos Santos was whisked away to an area for people who would testify. She would be called as a character witness, and to describe the last time she had seen Fabricio, driving off alone.

The officers each faced seven years in prison if convicted of both murder and fraud for having planted the gun.

An attorney for one of them said the pair would argue that they were fired upon by suspects on two motorcycles, even if no witness saw that and it wasn’t visible in the video.

The rest of the mothers gathered outside the courtroom, waiting to be let in. But 30 minutes passed. Then an hour. The mothers nervously sipped plastic cups of coffee.

Eventually, Dos Santos came back, her shoulders slumped. A lawyer for one of the defendants hadn’t showed up. The judge had postponed the trial until April.

Dos Santos had briefly stood in the same room as the officers, who were not in uniform.

“They assured me they are not working in the streets,” she said.

“At least they’re not killing anyone,” one woman muttered.

“We have to come back next year and come back with more people,” another woman told her.

Dos Santos went out the way she had come. The sky had clouded over and wind was picking up. A few fat raindrops fell as she and her sister said goodbye to the other mothers and boarded a bus that would take them back to the favela.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.