GUATEMALA CITY — It was a landmark piece of legislation for Guatemala: a law that established stiff prison sentences for violence against women and appeared to signal a new era for a country still emerging from decades of civil war and military rule. Thousands of men have been prosecuted under the law since it took effect in 2008.

But in recent years, public officials have found another use for it: stopping journalists from criticizing them or investigating corruption.

Courts have issued restraining orders against reporters at news organizations here, effectively shutting down their work, after women argued that the journalists violated the law by publishing articles that subjected them to psychological violence. The Los Angeles Times found eight such examples.

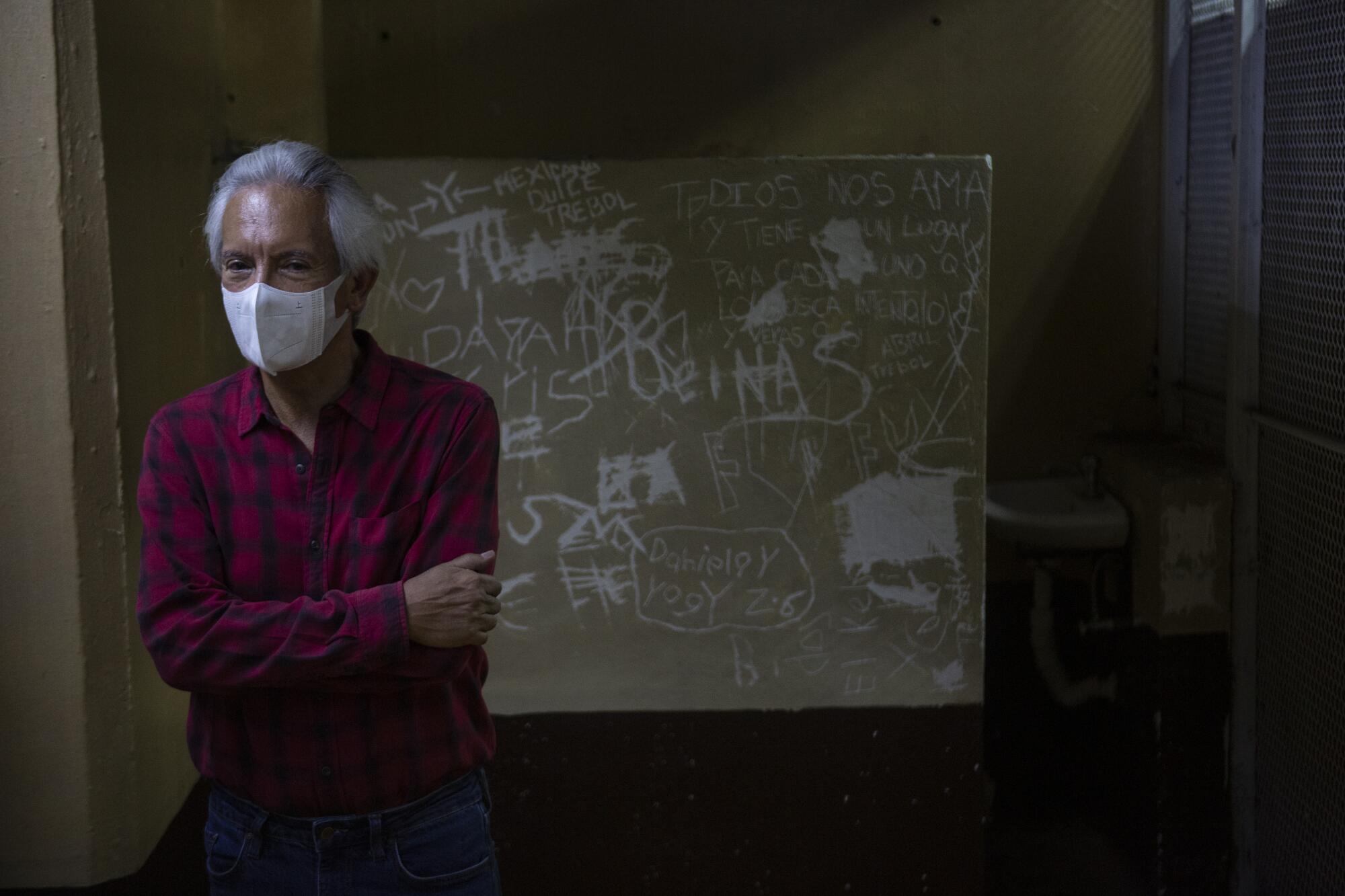

“We were investigating various cases, but we had to stop,” said Sonny Figueroa, an editor at the news site Vox Populi who was hit with a restraining order last year after he and a colleague published a story hinting at government corruption.

The article said that in 2020, when Luis Miguel Martinez was a top official in the executive branch, his parents moved from a modest house to a luxurious one owned by a Guatemalan diplomat, Demci Arnoldo López Villatoro.

López did not respond to the publication’s questions about the arrangement, and the journalists were unable to find Martinez, according to the article, which offered no evidence that a crime had been committed.

In a petition for a restraining order, Martinez’s mother and sister said they couldn’t sleep and were experiencing panic attacks; they accused Figueroa and his reporting partner, Marvin del Cid, of discrediting them “before Guatemalan society” and causing them “irreversible psychological damage.”

The judge ordered both reporters not to “disturb or intimidate” the women or their relatives, making no exception for Martinez. The reporters appealed, and two months later the judge lifted the order, ruling that the two “have done investigative work and their publications don’t contain any misogynistic act.”

Advocates for press freedom argue that misusing the femicide law to silence reporters is part of a larger threat to Guatemala’s fledgling democracy.

Recent attacks on Judge Miguel Ángel Gálvez are part of a broader campaign on Guatemala’s courts that have forced nearly two dozen judges and prosecutors into exile.

The country was long ruled by military regimes that carried out a brutal campaign against villages suspected of supporting leftist guerrillas. The war, which lasted more than three decades and claimed 200,000 lives, ended in 1996 with a peace accord.

For the next two decades or so, the nation sputtered along in that direction, holding free elections, establishing a truth commission to make peace with the past and partnering with the United Nations to form an anticorruption commission that strengthened the judiciary and led a president to resign.

But for the last several years, democracy in Guatemala has been backsliding.

The most significant blow came in 2019, when then-President Jimmy Morales expelled the U.N. commission after it began investigating him for illegal campaign financing.

Heavy-handed rule has continued under his successor, Alejandro Giammattei, and the United States issued sanctions against Guatemala’s attorney general after she fired the country’s top anticorruption prosecutor.

When it was passed in 2008, the Law against Femicide and Other Forms of Violence Against Women was widely hailed as an advancement for women in a country with high rates of gender-based attacks and killings.

The law, which set up specialized courts for such crimes, aims to protect women not only from physical harm but from what it calls “psychological violence.”

A guilty verdict for psychological violence carries a sentence of up to eight years in prison. Judges must consider such factors as whether the aggressor attempted to form an intimate relationship with the victim.

The law requires “a gender component and for the man to feel superior to the woman,” said Corinne Dedik, a researcher at the Center for National Economic Investigations, a Guatemalan think tank that has studied the law and found that prosecutors last year received nearly 60,000 complaints under it.

Few could imagine that the femicide law would be used to shut down journalists.

One of the earliest cases came in 2013, when then-Vice President Roxana Baldetti won a restraining order against José Rubén Zamora, the founder of El Periódico. Baldetti alleged that reports in the newspaper that were critical of her amounted to psychological violence.

Baldetti was eventually sentenced to 15 years in prison after being convicted of corruption charges for a scam involving the cleanup of a contaminated lake.

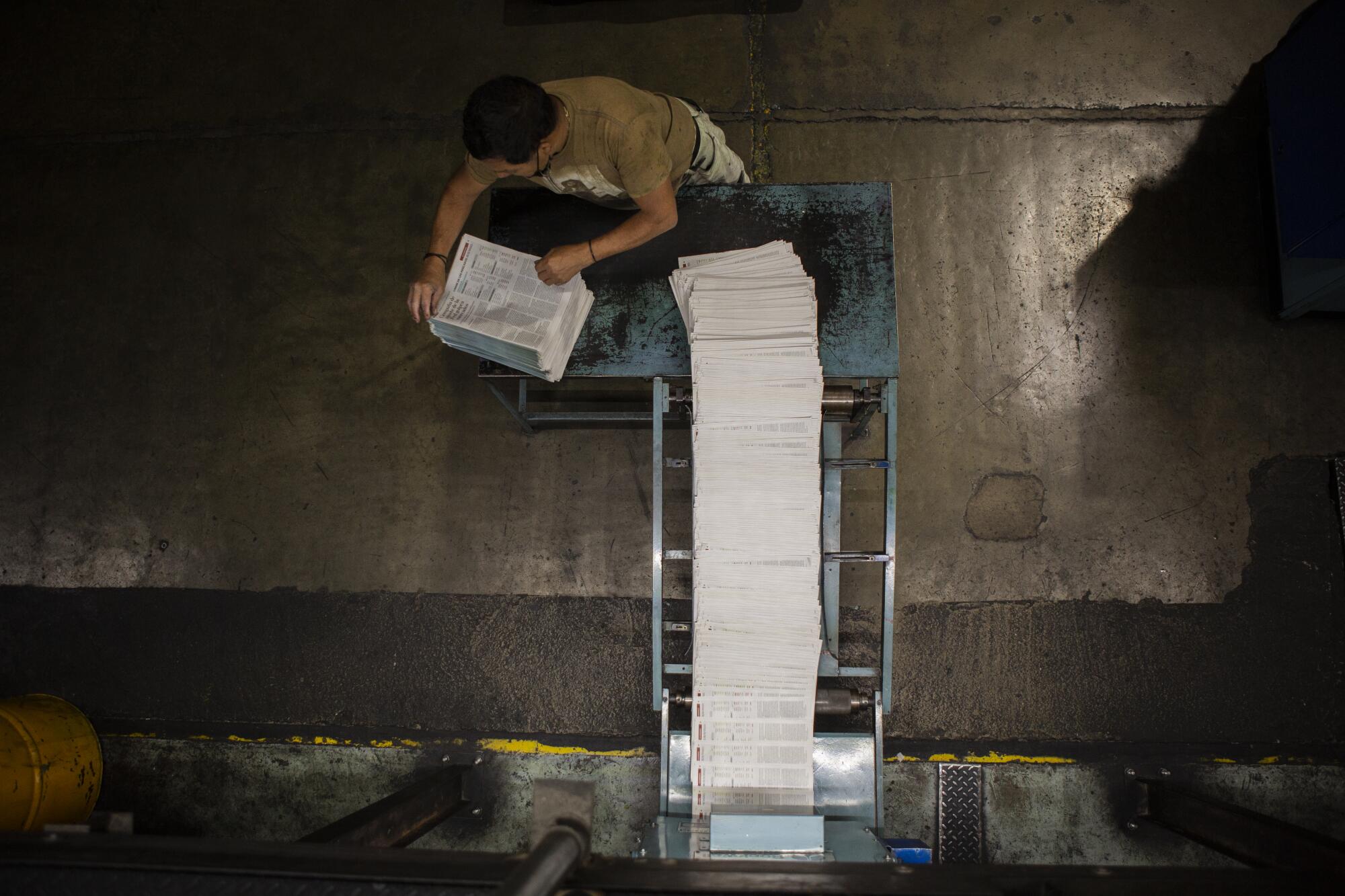

But that vindication of Zamora didn’t stop other female politicians from using the femicide law to obtain restraining orders against him and other journalists at El Periódico, which has about 30,000 print and digital subscribers.

Several, including Sandra Jovel, who was foreign minister at the time, said they were insulted by stories that appeared in a satirical section called “El Peladero” (the Peeler).

In her 2018 petition against Zamora, Jovel included an El Periódico article that discussed her antagonism toward the head of the U.N.-backed anticorruption commission and said it was embarrassing that Guatemala was represented “by someone so pathetic, grotesque and with evident and excessive intellectual limits like Sandra Jovel.”

Another submission, with the headline “The Gestapo in the foreign ministry,” said Jovel had implemented a “reign of terror” by prohibiting underlings from talking to journalists or human rights activists.

A judge ruled in her favor, prohibiting Zamora from going to her workplace or intimidating her.

The women in this report who filed restraining orders against journalists either did not respond to requests for comment or declined to be interviewed.

In 2019, Sandra Torres, a former first lady who was running for president, was upset about several El Periódico articles, including one that referred to her as “the tarantula Torres” and one that called her a “terrible Medusa” and said she would be in jail for corruption.

Following public backlash about the restraining order she was granted, Torres dropped her case, citing her “commitment to freedom of the press.” That didn’t stop the newspaper from publishing the front-page headline “You won’t silence us” in bold letters, with a picture of a hand holding a quill under the blade of a guillotine.

Guatemalan journalists say that if the subjects of their articles take issue with the reporting, they are welcome to file defamation claims. Such cases are rare, in part because they often get stalled in the bureaucracy of the legal system, according to Hector Coloj, who documents attacks on press freedom for the Assn. of Journalists of Guatemala.

He said female politicians have figured they stand a better chance in the femicide law courts.

“It’s easier,” he said. “The femicide law took many years to be approved, and it was approved because of all the machista violence. ... It’s a law that’s given a lot of importance to stop gender violence from growing.”

Natalie Southwick, a Latin American specialist at the Committee to Protect Journalists, said she could think of no legal rationale for why a judge would grant such restraining orders.

“It’s absolutely an abusive manipulation of this law,” she said. “This is a law intended to protect and provide victims some sort of redress of gender-based violence. It’s definitely not intended to protect powerful people from criticism in the media, which is how we’ve seen it be used in these cases.”

The Times sent interview requests to several of the judges who granted restraining orders, but none responded.

The first time Alejandra Carrillo filed for a restraining order against the directors of the small newspaper La Hora, the court rejected her petition.

Carrillo had objected to a series of articles about her leadership of the Victim’s Institute, a government agency that provides legal assistance to crime victims.

The articles said prosecutors were investigating the organization for questionable accounting and hiring practices and that a former assistant who was helping them — and had testified that Carrillo had begun to build relationships with Supreme Court judges to gain sway — was being attacked on anonymous Twitter accounts. They also pointed out that in 2021, Carrillo married a congressman who had been sanctioned by the United States for corruption.

Carrillo won an appeal in December granting her a six-month restraining order that was renewed in June, even though the prosecutor’s office had filed an opinion saying there was insufficient evidence that the journalists had committed a crime.

Early on in the case, the paper’s director, Pedro Pablo Marroquín, wrote in an opinion piece: “It’s not the first nor will it be the last time that people with a dark past try to undermine our work, our right to inform and express ourselves, so we’re here to continue the process and continue doing our work with professionalism, whatever the cost.”

But La Hora has stopped publishing investigations on Carrillo and the Victim’s Institute, and officials at the paper have declined to speak publicly about the case.

The latest dust-up over the law involves Dina Alejandra Bosch Ochoa, who reportedly has worked as an assistant at the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, which oversees the country’s elections.

She took issue with an article about her in El Periódico. It steered clear of making accusations but implied that she was unqualified for her job and was hired because her mother is president of the Constitutional Court.

Her petition for a restraining order said the story was part of “misogynistic campaigns” that had left her in “a permanent state of stress and insecurity in the short, medium and long-term that has reached my children.”

In April, a judge issued a six-month restraining order against Zamora, as well as an editor and the reporter who wrote the story.

These days, El Periódico is not publishing anything about Bosch, said Deputy Director Lucy Chay. Stories on sensitive topics may be published without the author’s name if editors think that a petition for a restraining order could be filed.

“You don’t know which official is going to use the law,” she said.

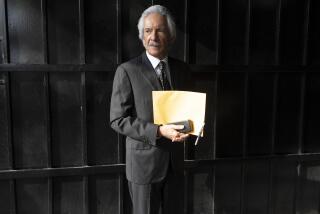

Zamora says officials are retaliating against him again.

In July, police arrested him based on testimony from a businessman who claimed that Zamora had asked him to launder about $38,000.

Zamora is in prison in Guatemala City, waiting for his case to progress through the legal system.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.