Making sense of a mass shooting in the middle of Texas gun country

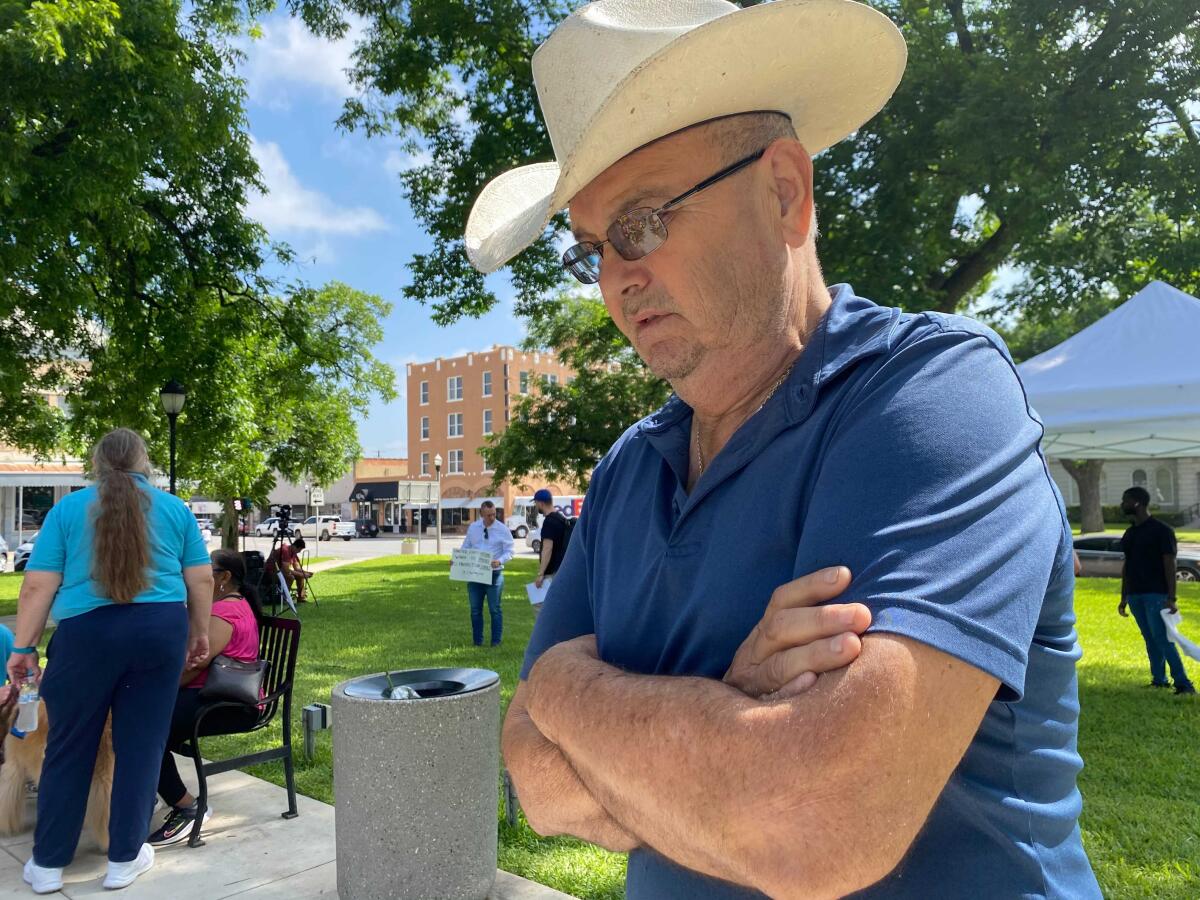

UVALDE, Texas — Randall Methvin is a thoughtful man who talks with a Texas twang, still works as a ranch hand at age 68 and has felt an affinity for firearms since childhood, when his Depression-hardened father would take him out quail and dove hunting.

By his count, Methvin owns four or five pistols, six shotguns and 15 rifles, give or take.

“I don’t hardly ever shoot them anymore, but when I do, I just go to the gun range, either at one of the ranches or one here in town,” the Uvalde resident said. “I just like to shoot at paper, I guess like some fellows play golf.”

Methvin doesn’t consider himself a Republican or a Democrat, but a conservative Libertarian. He doesn’t much care to bother anyone else, just doesn’t want others to bother him. And he wants to be an upstanding member of society, he said, in line with his Christian faith.

Methvin also thinks there should be stronger background checks for buying guns in the U.S., whether at a gun store or anyplace else, and that young men shouldn’t be able to buy assault rifles until they’re 21 years old. They certainly shouldn’t be able to buy more than one such weapon in a matter of days along with hundreds of rounds of ammunition without someone with more sense than the average teenager asking serious questions — and maybe even warning the cops, he said.

“I’m sure I could take a tongue-lashing from a friend or two for saying that, but I don’t care. That’s how I feel,” Methvin said in an interview with The Times. “We’ve got to start somewhere to put an end to this.”

There is some evidence to indicate that some victims may have been alive and in need of medical aid while authorities waited outside for backup.

Methvin, of course, was referring to the horror of unceasing massacres by young gunmen across the United States, and now in his town too. The largely Latino city of 16,000 west of San Antonio was shattered Tuesday when an 18-year-old with an AR-style rifle, one of two he’d recently bought, went into Robb Elementary School and fatally shot 19 children and two teachers with a torrent of rounds.

“These babies who died the other day?” Methvin said, choking up. “It’s heartbreaking.”

As in other conservative and semi-rural places in this country where mass shootings have occurred, the discussion around guns in Uvalde in recent days has caused a fair amount of cognitive dissonance for outsiders trying to make sense of it all, including the journalists who arrived in droves in search of interviews.

Guns were never far from the line of questions being asked, but have rarely been the first subject out of the mouths of residents, who sometimes bristle at such inquiries and other times pause before answering them, wondering whether their words might ostracize them in the days and weeks to come.

Uvalde, like a lot of America, is gun country, plain and simple, where most people have other contexts for firearms than massacres and many see evil in the gunman, not the weapon he used. Not even a mass shooting, Methvin and others said, is going to change that overnight.

“Even though that weapon destroyed this town momentarily and turned it upside down, it just happened to be used that way,” Methvin said. “That same weapon could have been used in a much more sporting, ethical situation, in a much more fun type of activity if you will, than what it got used for.”

Still, that doesn’t mean all the years of American myth-making around these incidents — about rural and conservative people blindly defending their guns, even in the face of tragedy and without budging — are helpful, or even true. It doesn’t mean all the stern men in cowboy hats think the same way, or even resent the discussion about guns when you come by it with genuine interest in where they stand.

Denial is a stage of grief, but no one in Uvalde is denying their children are gone, or that something terrible involving such a powerful rifle happened here. It would be impossible to do that.

Undeniable now is that a troubled 18-year-old with sufficient cash on a debit card was able to obtain enough firepower within a matter of days to somehow deter 19 or more police officers from storming schoolrooms where the massacre took place in the course of an hour.

Local law enforcement leaders have said it’s still unclear exactly why a supervisor on scene hadn’t allowed his officers to heed the desperate 911 calls from children inside, asking them to rush into the school. But the bottom-line answer is that a lone murderous young man had a weapon of war.

The power of Salvador Ramos’ weapon was not a circumstantial aspect of the attack, but a central one. Texas Department of Public Safety Director Steven McCraw said Friday that Ramos had unleashed a “barrage” of gunfire at the school.

“Hundreds of rounds were pumped in, in four minutes, into those two classrooms,” McCraw said.

Lost on no one listening, including the line of other law enforcement leaders standing behind McCraw and in front of mounds of flowers stacked up for the dead, was that, at just about the same time, Republican leaders and the gun lobbyists who fill their campaign coffers were meeting in another part of the state for a National Rifle Assn. conference.

They had gathered in Houston to discuss what the NRA discusses, which is how they believe access to firearms, including the type used by Ramos, is too restricted. They met to say that guns should be sold more easily, and disseminated more prolifically. That despite the certainty that such weaponry will continue to cause carnage and death in places just like Uvalde across the country, without mercy, on a devastatingly regular basis.

This was not a conversation being freely had in Uvalde that day though. Gov. Greg Abbott, who skipped the convention to be in town, repeatedly dismissed calls for more gun regulation during his own news conference at Uvalde High School.

Yet that morning, Hector Olivarez, 70, in cowboy hat and boots, slowly walked around the town’s central square, looking at each of the 21 white crosses bearing the names of the dead and scrawled with messages from friends and family.

Olivarez’s granddaughter was in Robb Elementary on the day of the shooting and escaped. His wife and sister are both teachers in town. And he is a retired deputy sheriff for Uvalde County, who worked as a deputy and bailiff at the courthouse on the edge of the square for 20 years.

With a quiver of emotion on his lower lip, he said: “We haven’t slept at all.”

Olivarez is strong, he said. He’s a Vietnam veteran. He doesn’t take any bull, and never did as a deputy. And guns are a fine thing to own, he said.

“But why let somebody buy guns barely even 18, and those two assault guns? That’s a red flag,” he said. “Where are you going with them? You’re not stacking them in a closet.”

Olivarez too is frustrated that an 18-year-old was able to arm himself like he did without anyone intervening. He’s frustrated that so many officers held back for so long before rushing in to kill Ramos, he said. And he thinks things need to change and will, but most immediately around security — both at schools and in town in general. People and authorities will be more cautious.

There are ways gun laws should be tightened, he added — though nobody should be coming to take away responsible gun owners’ firearms. He won’t be giving up his.

“I don’t want anybody taking my guns. I need them to protect myself and my wife and my kids and my property,” he said. “I ain’t going to go use them like [Ramos] did.”

A few hours later, Grace Hernandez, 69, stood in a grassy area to the side of Highway 90 in Uvalde, hammering one of 21 white wooden crosses — one for each victim — into the ground.

Hernandez had come with others from their San Antonio church every day since the shooting to lend support in any way they could, she said. They thought the crosses would be a welcome sign for folks headed into town, she said, with the attached blue and red butterflies symbolizing that the victims “have been freed from the suffering they were placed through.”

Hernandez said that stronger gun regulations are clearly needed in Texas, and not just because of what happened in Uvalde. There’s been a string of mass shootings in the state, she noted. Where is the change?

“Everything that needs to happen should have happened yesterday — like, long ago,” she said. “It’s an embarrassment to Texas. It’s an embarrassment that our governor hasn’t opened his eyes up to what is happening.”

Hernandez, at the same time, mentioned as inappropriate a confrontation between Abbott and his Democratic challenger, Beto O’Rourke, two days prior, where O’Rourke interrupted a news conference, pointed at Abbott and said, “This is on you until you choose to do something different.”

A second showdown would occur later on Friday when state Sen. Roland Gutierrez, a Democrat who represents Uvalde, would interrupt another Abbott news conference to demand the governor call legislators back for a special legislative session to pass meaningful gun regulations.

Hernandez said such incidents “looked bad for both sides,” particularly given that the children killed at Robb haven’t even been buried yet. “Both sides need to think of the children,” she said.

That said, once all the victims are laid to rest, Hernandez said she plans to protest for more gun laws in San Antonio.

Such thoughts are not prevailing in Uvalde, about 80 miles west of San Antonio, 50 miles from the Mexico border, and its own place entirely in the middle of Texas hill country.

Driving from San Antonio to Uvalde, one passes big ranches and signs for dove hunting, bow hunting and sales of guns and ammunition alongside liquor. There are taxidermists and churches, fast-food chains and antique shops.

The city of Uvalde is bigger than the towns that surround it, and the county seat of Uvalde County. Faith runs deep here, and so does gun culture. The old Inn of Uvalde in town touts itself as the “Home for the Hill Country Hunter.” There’s a gym in town called M-16, “where every round counts.”

Amid the deluge of visiting reporters, who carry reputations for being anti-gun, many folks here have been hesitant to talk. The Oasis Outback gun store in town had private security officers stop reporters outside and escort them to the edge of the property. Some residents, asked about guns, said they didn’t want to talk politics. At a vigil the night after the shooting, guns went entirely unmentioned.

Some younger residents will share thoughts in longer chats about the need for gun control. M.J. Salazar, a 36-year-old tax preparer and counselor, said she’s “on the side of saving lives” with more gun restrictions. Sandra Bateman, 18, said she was taught gun safety from a young age growing up in Uvalde and has no problem with people using guns safely, but doesn’t think people her age should be able to buy an AR-style rifle — even if her friends disagree.

“It’s all over my Facebook and Twitter, the right to bear arms,” she said. “I get it. But if a child can’t drink at 18, why can they buy an AR?”

Others are outspoken about their fierce opposition to any new gun restrictions.

Robert Rodriguez, 74, a retired butcher, grew up in Uvalde, raised his four children here, moved to Dallas but returned because his hometown felt safer. He said he was troubled to see President Biden and Texas Democrats blame the mass shooting on gun laws.

“Biden can stay in Washington. Charlton Heston is my president,” Rodriguez said, referring to the late actor and longtime NRA stalwart. “They shouldn’t go after the gun owners.”

Rodriguez wore the Texas rancher’s standard uniform: straw cowboy hat, pearl snap Western shirt, pressed Wranglers and boots. A born-again Christian, Rodriguez carries Scripture in his breast pocket and blames mass shootings on an erosion of American values, not gun laws.

“Everybody owns guns here,” he said. “As kids, we shot .22s to have meat on the table.”

Rodriguez said he doesn’t think people need AR-style rifles but doesn’t support any restrictions on them, because if “you give these leftists an inch, they take it all.”

Methvin said he’s heard such arguments from friends. He knows such beliefs are held by lots of folks around Uvalde. And he doesn’t want to see the local gun culture come under attack either, he said.

He doesn’t hunt much anymore, preferring now instead to photograph “all of God’s creatures” that inhabit this patch of Texas. But hunting still holds a place in his heart, he said, recalling a recent visit from his son, back home from the Navy, when they went out in a 15-foot-high hunting box one morning to shoot turkey and wild hogs.

At one point, he looked over and his son was leaned back, sound asleep. It reminded him of his days with his own father, and swelled his heart. He couldn’t help but just watch his son for a bit, enjoying the father-son moment.

However, Methvin said he also knows there’s room for change, and doesn’t begrudge that. He wishes others felt the same.

The politics of animosity and vicious divisions, of shouting at each other and refusing to budge one bit in the direction of the other side? “It’s just getting old,” he said.

“Neighbors … never get anything done by bickering,” Methvin said. “We need to come together.”

Times staff writer Molly Hennessy-Fiske contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.