How Big Tobacco used George Floyd and Eric Garner to stoke fear among Black smokers

ATLANTA — Retired Deputy Police Chief Wayne Harris stood in front of Black lawmakers and clicked to a slide of George Floyd, pinned down on the pavement with Police Officer Derek Chauvin’s knee on his neck.

“I chose this picture intentionally because I want to set the tone,” he said.

But Harris hadn’t come to the luncheon to discuss police reform or Floyd’s murder.

He was there at the invitation of tobacco maker Reynolds American to urge representatives not to ban menthol cigarettes, the flavor of choice for the vast majority of Black smokers. Using the specter of Floyd’s tragic death and the social justice protests it inspired, Harris suggested that prohibiting menthol cigarettes would increase policing in Black communities and create a new layer of racism in America.

That message echoed through the third day of the annual gathering of the National Black Caucus of State Legislators at the Marriott Marquis hotel in Atlanta in November. Harris did not mention that he serves as chair of the board of the Law Enforcement Action Partnership, an organization that in 2019 received a third of its funds from Reynolds American.

The lawmakers were told during the first course that the $40,000 bill for their lunch — pork chops and sweet tea — had been picked up by that same company, the largest manufacturer of menthol cigarettes in the U.S.

Reynolds American’s multibillion-dollar market is under threat. About 150 cities and counties have placed some sort of restriction on the sale of menthol cigarettes, most issuing an outright ban. If California votes to prohibit the sale of menthols in November, it would follow Massachusetts as the second state to do so. The Food and Drug Administration has drafted a national ban that could follow in the next few years, which estimates suggest could save more than 600,000 lives, including almost 250,000 Black lives.

But it could cut the approximately 30 billion Newport menthol cigarettes Reynolds American sells every year to zero.

Since last summer, the Los Angeles Times and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism have tracked strategic efforts across the country by Reynolds American to keep menthol cigarettes in the hands of smokers.

The company has hired a team of Black lobbyists and consultants, including former congressman Kendrick Meek (D-Fla.), and sponsored the organization led by civil rights activist and MSNBC political show host the Rev. Al Sharpton. Those figures have in turn stoked fears among Black communities about what the bans could mean.

Reynolds American for years has enlisted prominent Black personalities in its lobbying efforts. This investigation has uncovered new details about how individuals and organizations working on Reynolds’ behalf have failed to properly declare their links to the company. Lobbyists for the company in Denver successfully killed a bill that would have banned menthol cigarettes. And in Los Angeles, protesters were paid to attend a rally organized by a group with close ties to the company.

“The web that keeps menthol present in cities is not an accident. It’s not driven by some kind of innate Black taste for menthol,” said Keith Wailoo, a history professor at Princeton University and author of “Pushing Cool,” a book about menthol cigarettes. “It is a byproduct of a complex and relentless story of how markets were built and sustained.”

In response to a list of questions, Reynolds American told reporters it believed that “regulating menthol cigarettes differently than non-menthol cigarettes would result in numerous troubling unintended consequences, including significant growth in contraband menthol cigarettes sold through an already widespread underground market.”

The company did not address questions regarding its invoking of police brutality fears to protect its sales.

Wearing a dark suit and a buzz cut, Harris followed that narrative at the luncheon, when he gestured to an image of Floyd taken outside the store known as the best place in Minneapolis to buy menthols. The inference was: What happens if Black people can’t legally buy the cigarettes they prefer? Harris warned that driving the market underground would result in intrusive policing and racial friction in Black communities that already feel unfairly targeted by law enforcement.

“I want us to keep in mind not only the murder of this man on the streets in Minneapolis but the unrest that occurred afterwards,” said Harris, speaking to hundreds of Black lawmakers and their staffs. “I want to talk to you about how policing intersects with the community and how decisions that you make as legislators, as citizens, impact how we end up dealing with people on the streets.”

Harris’ organization, known as LEAP, said the push toward menthol bans is “the latest iteration of the drug war except that it — more than most laws you see these days — is overtly racist.” When asked about Reynolds American’s funding, LEAP said its “message has been the same for two decades, and if someone wants to donate to us to say it, bully for them.”

But other Black advocacy groups, including the NAACP, “applaud” efforts to ban menthol cigarettes, saying that the “tobacco industry is on a narrow quest for profit, and they have been killing us along the way.”

Tobacco-related cancers claim 40,000 Black lives each year, at a rate 17% higher than that for whites and 74% higher than for Asians and Latinos, according to most recent data. But Harris did not warn against life-threatening illnesses associated with smoking. His mission was to ensure that menthol cigarettes — a gateway to hooking young people — stayed legal.

Cooler than cool

Menthol itself is deceptive. Suck on a menthol cough drop and you’ll feel your airways open up, a cooling breeze as you breathe in and a momentary easing of the scratchiness in your throat. That’s an illusion — the result of a reaction between the menthol and the receptors on the surface of your nerves.

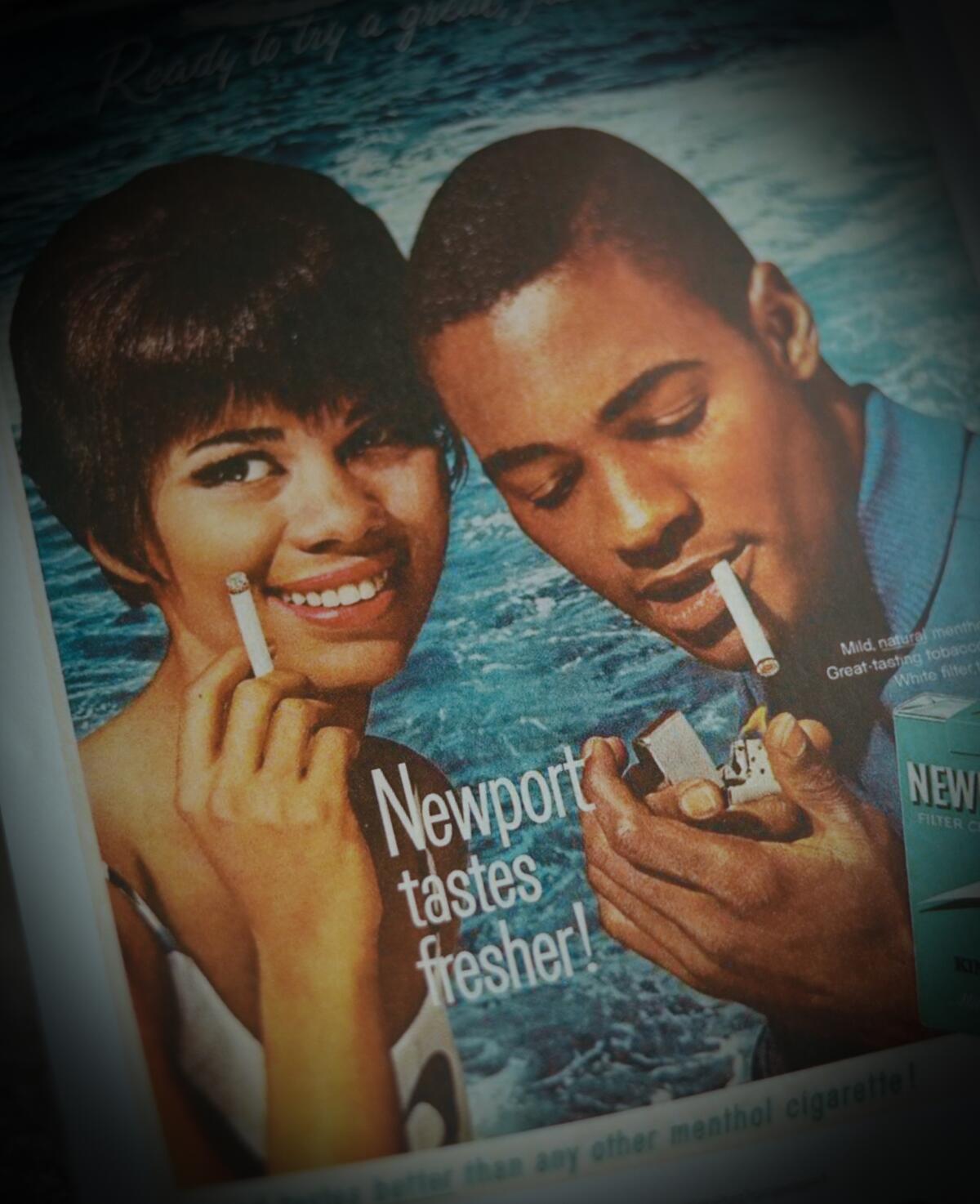

Wailoo remembers the billboard ads that towered over the sidewalks in 1970s New York City, a minty-green canopy that pushed the fresh, smooth taste of a menthol cigarette. It was a product dating to the 1920s, repackaged as new to target the large, concentrated Black population in America’s rapidly changing cities.

The tobacco industry, whose early success was built on slave-run tobacco plantations, had studied Black culture to fine-tune marketing. At times, it came to conclusions based on old racist tropes, such as one 1970s marketing memo that suggested that Black people prefer menthols because they are “said to be possessed by an almost genetic body odor.” But the companies also broke new ground.

“I grew up reading Black publications like Ebony and Jet, and menthol was all over it,” said Wailoo, the history professor and author. Tobacco companies sponsored events and handed out free menthols, often to kids in Black neighborhoods. Looking back, Wailoo now realizes he grew up at the “high point of the racialization of menthol smoking.”

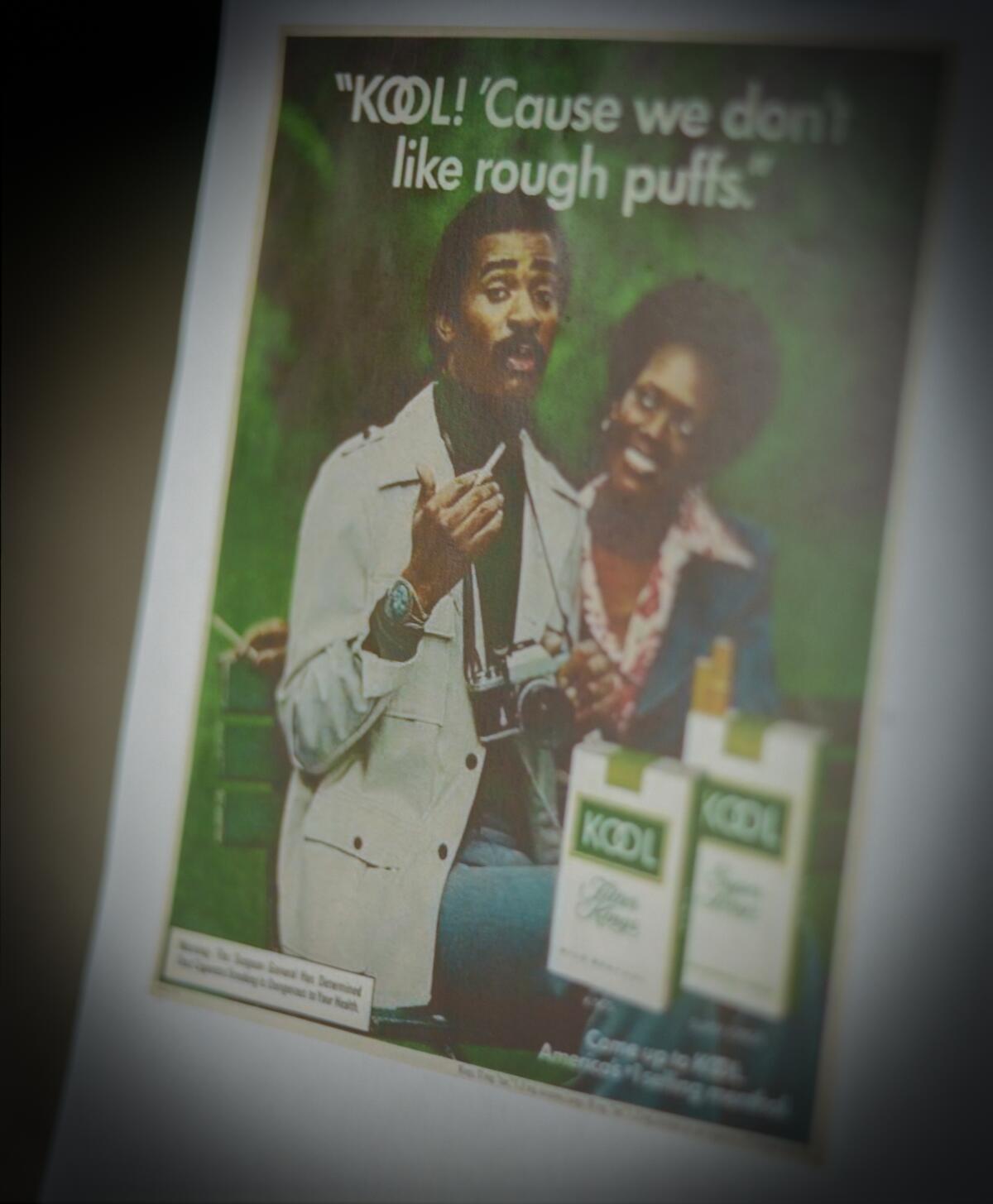

A 1970s study in Detroit commissioned by R.J. Reynolds (which became a subsidiary of Reynolds American when the company merged with British American Tobacco in 2004) examined how the company should advertise on predominantly Black buses that passed through white neighborhoods. The company was concerned that white smokers would be put off by ads for brands such as Kool and Newport that featured Black models and culture.

The authors concluded that the buses’ “exterior advertising should be compatible to both market segments” but that “interior advertising should specifically address this [Black] group.”

A multibillion-dollar lawsuit in 1998 against the country’s four largest cigarette makers severely curbed how the industry could advertise. Although the billboards that Wailoo remembers are gone, the demand for menthol cigarettes among Black smokers persists. In the 1950s, 2% of white smokers chose menthols, compared with 5% of Black smokers, according to an industry survey. Today, that 3% gap has grown into a chasm: Menthol is the choice for 30% of white smokers and 85% of Black smokers.

Paid protesters

For three hot hours on the morning of June 15, 2021, protesters stood outside Los Angeles City Hall wielding signs carrying messages such as “No ban on menthol” and “Whites can smoke. Blacks cannot.”

On the back of their matching white T-shirts was the logo of the organization that had arranged the rally, Neighborhood Forward, a new, relatively unknown group led by a local pastor.

Describing itself on Twitter as “a collective of real voices from Black and Brown communities working together to bring about real change,” the group emerged after Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis in 2020. It has since taken aim at California’s plan to ban flavored tobacco, which includes menthol. The Senate bill, known as SB 793, was made law in August 2020. But a petition against it signed by more than 600,000 voters pushed it to a referendum due in November. To date, R.J. Reynolds and Philip Morris USA have spent more than $20 million on a campaign to block the bill.

“California fought Big Tobacco and won,” the bill’s author, then-state Sen. Jerry Hill (D-San Mateo), said when R.J. Reynolds first indicated it would seek a referendum. “This shameless industry is a sore loser and it is relentless.”

Before that June rally, a text message had gone out to recruit protesters: “Menthol T-shirts will be provided. … The pay is $80 for 2½ - 3 hours.”

Pastor K.W. Tulloss, Neighborhood Forward’s public face, is a former leader of the local chapter of the Sharpton-led civil rights group National Action Network, which has been funded by Reynolds American. Tulloss was happy to speak about the work that Neighborhood Forward was doing to fight SB 793. But when asked where the group got its money, he said that “we can’t focus on those sidebar conversations” and that reporters should “check public records.”

Little public information exists about Neighborhood Forward. Although the Los Angeles-based Tulloss is often described as the group’s co-founder, business filings lead 1,500 miles east, to Missouri. There, the group was incorporated by Charles Hatfield, a lawyer specializing in government relations litigation. Asked to explain how his role with Neighborhood Forward, a small grass-roots movement, fitted with this work, Hatfield said: “I don’t feel any obligation to help you with that.”

Even the person listed as the chair of Neighborhood Forward’s board, the Missouri-based lobbyist Leroy Grant, declined to answer basic questions about the organization and his interest in menthol cigarettes. “I’m not really able to speak on that issue,” he said before hanging up the phone.

Although public records do not show how the group is funded, they do reveal that one of its directors is the California-based lobbyist Ingrid Hutt. She worked for Reynolds American for several months in 2019, hired to “promote the unintended consequences of the menthol ban in the African-American communities in the City of Los Angeles,” according to lobbying disclosures. She did not respond to multiple attempts to reach her.

Another director is Corey Pegues, who was once associated with a Reynolds American-funded group called the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives, or NOBLE. Tulloss said NOBLE, which has campaigned across the country against menthol bans, first brought the issue to his attention.

Reynolds American did not comment on these points.

“These Black leaders act as if menthol cigarettes just drop from the sky and are not the result of decades of racist, pernicious targeting. They allow these ... tobacco industry executives to cynically exploit our legitimate grievances,” said Carol McGruder, co-founder of the African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council. “The time of this being acceptable is long past.”

Thriving off addictions

Almost all African Americans who smoke started with menthols. The product has helped recruit an estimated 10 million extra U.S. smokers since 1980, and research suggests that menthols can be harder to give up. This may explain why Black smokers try to quit more than white smokers, but they are less likely to succeed.

Menthol cigarettes are often cheaper in predominantly Black neighborhoods, where store owners have sought contracts with manufacturers of the most popular brands.

When President Obama signed into law a ban on flavored cigarettes, members of the Congressional Black Caucus, which has received hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations from the tobacco industry, were seen as key in securing an exemption for menthol. Many members of the caucus have since come out in support of a nationwide ban on the sale of menthol cigarettes.

The industry has grown ever more reliant on revenue from menthols. Last year, they made up more than a third of total cigarette sales, the highest proportion ever. LaTrisha Vetaw, who campaigned for banning their sale in Minneapolis, described menthols as the industry’s “cash cow.”

Reynolds American brought in about $15.3 billion in U.S. sales last year. About half came from Newport cigarettes.

“If menthol is banned, you know they’ll lose a lot of money, so they’re paying off a few Black men to go out and try and stop it,” said Vetaw. “They know who has a voice in our community.”

Sharpton and Meek did not respond to multiple inquiries from The Times. But in the past, Sharpton has cited the 2014 death of Eric Garner at the hands of police in New York to argue against a ban.

“They killed him over ‘loosie’ cigarettes,” he said at a 2016 forum held in an Oakland church, referring to allegations that Garner was illegally selling single cigarettes. “How many of these kind of situations are we going to have if we keep having these kind of engagements around criminalizing of low-level offenses?”

Public health advocates stress that the policies target the sale of menthol cigarettes, not their use, which should ease concerns about how the bans could lead to greater policing of Black communities. But there are few more prominent voices in Black communities than pastors like Sharpton and Tulloss.

“Even going back to the period of enslavement, often [Black] preachers were looked to be the spokespersons” for the Black community, said Obery Hendricks, a scholar at Columbia University who has studied the intersection of religion and political economy. “The tobacco industry knows the hold that Black pastors have over Black churches.”

Meek’s firm arranged meetings this month with the White House’s Office of Management and Budget — responsible for evaluating the FDA’s proposed ban — for both Reynolds American and Sharpton’s National Action Network.

Despite the number of Black lobbyists working on behalf of the tobacco industry, there is a significant lack of Black representation across executive-level and board-level positions at all the major cigarette makers. Compared with those who have lobbied for Reynolds American against banning menthol cigarettes, almost all of the company’s senior management team is white.

Positions of power

Denice Edwards sat in the back row of the committee room on the fourth floor of Denver City Hall. She was wearing all black, but her shock of amber hair stood out, even among the crowd of campaigners wearing loud T-shirts with slogans sprawled across their chests.

Denver’s Safety, Housing, Education and Homelessness committee was debating a bill that would ban the sale of flavored tobacco, including menthol cigarettes. It drew more people to City Hall than any other time since the start of the pandemic, and unusually, it was being discussed by the committee for the third time.

Unlike many of those in the audience on that brisk November morning, Edwards, who is staunchly opposed to banning menthols, wasn’t there to speak. Her work had already been done. She’d spoken to a number of the council members ahead of the meeting. She was simply “monitoring the issue.”

Councilmember Kevin Flynn, who sits on the committee, had proposed an amendment to the bill that would exempt menthol cigarettes from the ban.

“She just called me up and asked for a meeting,” Flynn said of Edwards, whom he’s known for decades. “It was before the bill was even introduced. … Denice was actually the first person who approached me about it.”

But Edwards isn’t just an old acquaintance. She’s a lobbyist hired by Reynolds American — one of at least three consultants working for the company on this issue in Denver. Although Flynn said he was aware of her ties to a tobacco company, she didn’t disclose them on the city’s lobbying register. Edwards did not reply to questions about her failure to properly register, as Denver’s municipal code requires.

The scenario also shows how Reynolds American consultants have been key in furthering the company’s interests in levels of government it has rarely lobbied before.

It felt “very uncomfortable for me, as a white man, to be asked to tell my Black constituents, ‘You can’t buy this anymore,’” Flynn told a reporter. “The tobacco industry has marketed just like any industry markets to its target market, right? … I wish they wouldn’t do it at all, but I’m not going to single out Black consumers.”

Flynn and Edwards first met when he was a reporter at the local paper, the Rocky Mountain News, and she was working for the city’s first Black mayor, Wellington Webb. Nearly two decades after he held office, Webb, whose famous door-to-door campaigning shoes are on display at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, remains a huge figure in Denver. In early October, not long before Flynn introduced his amendment, Webb wrote an opinion piece for the Denver Post, mentioning Garner’s death.

“Law enforcement hardly needs more reason to stop us from going about our lives. But that’s what a menthol ban could do,” Webb wrote. (When asked about the menthol ban, Edwards said: “I’m on the side of Mayor Webb.”)

A few weeks later, Webb’s opinion piece was removed from the newspaper’s website. A correction in print noted that he had not told the editors he was working as a consultant for Reynolds American.

He did not respond to multiple inquiries for comment.

A few doors down the corridor from the committee room in Denver City Hall, Councilmember Amanda Sawyer, who co-sponsored the bill that would ban the sale of flavored tobacco, had been doing the math. In purple marker on a whiteboard were the numbers 1 to 13. A series of crosses and dashes next to each indicated how she thought the 13 members of the City Council might vote on the bill and its amendments. By her estimation, she had the numbers.

Indeed, as Sawyer predicted, Denver’s City Council voted in favor of banning almost all types of flavored tobacco, including menthol cigarettes, in December. Despite Edwards’ efforts, the amendment to exempt menthol had failed. All that was left was for the city’s mayor, Michael Hancock, to sign the bill into law.

But another Reynolds American consultant, Art Way, who had previously spoken with the mayor’s staff about the proposed ban, wrote to Hancock’s office imploring him to veto the bill, according to emails released in response to a public records request.

“Unfortunately, it is the very communities the ban is supposed to protect that will engage in grey market activity increasing the spectrum of criminality for both youth and adults of color,” wrote Way. But nowhere in his email did Way explain his ties to Reynolds American. And like Edwards, he is not on the city’s lobbying register. He told a reporter he believed his state registration would suffice.

Way also said that his email, one of dozens sent to the mayor’s office on this issue, “was likely no more beneficial than others.” He added: “In order to water down my message, flavor ban proponents … would like me to shout from the rooftop regarding my client. I’ve disappointed in this regard on occasion but never purposefully tried to hide my affiliation.”

In his 11-year tenure Mayor Hancock had vetoed just one bill.

The day after Way’s email arrived, the mayor wrote a letter to the council members. The bill banning menthol cigarettes had become the second.

About this story

This story was a collaboration between the Los Angeles Times and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a nonprofit newsroom that works in partnership with major news outlets around the world on public interest journalism. It was reported by The Times’ Emily Baumgaertner and by Ben Stockton and Ryan Lindsay for the Bureau.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.