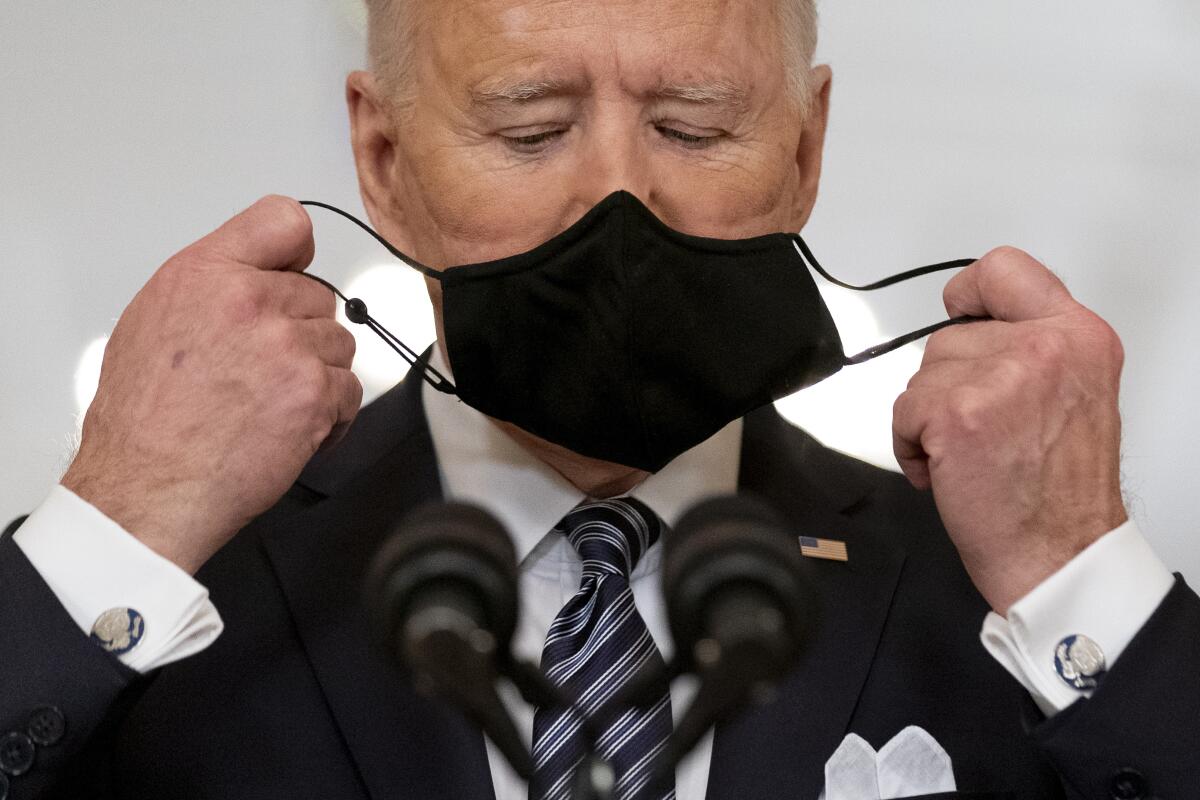

After Biden’s first year, the coronavirus and disunity rage on

WASHINGTON — From the inaugural platform, President Biden saw American sickness on two fronts — a disease of the national spirit and the one from the rampaging coronavirus — and he saw hope, because leaders always must see that.

“End this uncivil war,” he implored Americans on Jan. 20, 2021. Of the pathogen, he said: “We can overcome this deadly virus.”

Neither malady has abated.

For Biden, it’s been a year of lofty ambitions grounded by the unrelenting pandemic, a tough hand in Congress, a harrowing end to a foreign war and rising fears for the future of democracy itself. Biden did score a public-works achievement for the ages. But America’s cracks go deeper than pavement.

In this midterm election year, Biden confronts seething divisions and a Republican Party that propagates the delusion that the 2020 election, validated as fair many times over, was stolen from Donald Trump. That central, mass lie of a rigged vote has become a pretext in state after state for changing election rules and fueling even further disunity and grievance.

The hostage taker was killed after authorities entered the building, and the FBI said a team would investigate ‘the shooting incident.’

In the dispiriting close of Biden’s first year, roadblocks stood in the way of all big things pending.

The Supreme Court blocked his vaccinate-or-test mandate for most large employers. Monthly payments to families that had slashed child poverty ran out Friday, with no assurance they will be renewed. Biden’s historic initiative to shore up the social safety net wallowed in Congress. And people under 40 have never seen inflation like this.

After his lacerating speech in Atlanta invoking the darkest days of segregation, he saw his voting-rights legislation run aground when Democratic Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona announced her opposition to changing Senate rules to allow the bill to pass by a simple majority.

Altering the rules would only “worsen the underlying disease of division infecting our country,” she said.

For all of that, Barack Obama was on to something when he paid his old vice president an odd compliment late in the 2020 campaign. Elect Joe Biden, he said, and after four years of flamboyant Trump dramas, folks could feel safe ignoring their president and vice president for a spell.

“You’re not going to have to think about them every single day,” Obama said. “It just won’t be so exhausting. You’ll be able to go about your lives.”

Indeed America saw normalcy, some say dignity, return to the White House. Pets came back and so did daily press briefings for the public.

The Trump-era political muzzle came off public-health authorities, freeing them to confuse the public all on their own.

First Lady Jill Biden’s studded “Love” jacket at a global summit not-so-subtly countered the “I Really Don’t Care, Do U?” jacket her predecessor wore in a visit to a migrant child detention center.

The discipline, drive and baseline competence from the new White House produced notable results. Biden won a bipartisan infrastructure package that had eluded his two predecessors, coming away with a legacy-shaping fix for the rickety pillars of industry and society.

Biden steered more judges through Congress to the federal bench than any recent predecessor. He won approval of a Cabinet that was half women and a minority of white people for the first time. More than 6 million people are back at work and half a billion COVID-19 vaccines have been put in arms, but the nation has a long way to go to return to its pre-pandemic state.

“I think it’s a lot of achievements, a lot of accomplishment, in the face of some very serious obstacles,” Biden’s chief of staff, Ron Klain, told the Associated Press on the cusp of Biden’s second year. “The Biden presidency remains a work in progress.”

Matthew Delmont, a civil rights historian at Dartmouth, expected more from Biden by virtue of his decades of experience as a savvy operator in the capital.

He had anticipated a far more effective COVID-19 response and more urgency, sooner, in countering the rollback of voting rights and tilting of election rules that Republicans are attempting.

“There’s something to be said for the professionalism of the White House and not going from one fire to the next,” Delmont said. “What I worry is that the Washington he understands isn’t the Washington we have anymore.”

Political science professor Cal Jillson at Southern Methodist University in Dallas said Biden has displayed “warning track power” — the ability in baseball to hit long but not, as yet, over the fence.

In Biden, Jillson sees a leader who brought the even keel that Obama had talked about but also one who only rarely delivers a speech worth remembering.

“While there are vast partisan differences in how Biden is seen, in general he is seen as stable but not forceful,” he said.

In large measure, Biden’s innate civility and predictability brought the sort of climate change that the world could get behind.

Here once more was a president who believed deeply in alliances and vowed to repair an American reputation frayed by the provocateur in office before him.

There would be no more puzzling feelers about buying Greenland. No more doting looks at Russian President Vladimir Putin — instead, Biden stepped up diplomatic confrontation over Putin’s designs on Ukraine. There would be no eerie uplit gatherings around glowing orbs with rulers of dissent-crushing Arab countries like Trump’s photo op with the Saudis.

But the world also witnessed Biden’s debacle in Afghanistan, a chaotic withdrawal that brought more than 124,000 to safety but stranded thousands of desperate Afghans who had been loyal to the U.S. and hundreds of U.S. citizens and green-card holders.

Discounting warnings from military and diplomatic advisors, Biden misjudged the Taliban’s tenacity and the staying power of Afghan security forces that had seen crucial U.S. military support vanish. He then blamed Afghans for all that went wrong. Millions of Afghans face the threat of famine in the first winter following the Taliban takeover.

All presidents enter the world’s most powerful office buoyed by their victory only to confront its limitations in time. For Biden, that happened sooner than for most. A polarized public, Trump’s impeachment trial and an evenly divided Senate saw to that.

Meantime, day after day, event after event, it was the virus that commanded Biden’s attention. “That challenge casts a shadow over everything we do,” Klain said. “I think we’ve made historic progress there but it’s still a challenge.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.