With pressure from the United States, Mexican immigration enforcement holds migrants in the south of the country, where many feel they have no choice but to request asylum there. After so many requests for protection, the system collapsed.

TAPACHULA, Mexico — It took Denaud two months to travel across nine countries, starting in Chile, to reach Tapachula, a city in southern Mexico near the border with Guatemala. It took him a year and a half more to cross Mexico to reach the San Diego-Tijuana border to request asylum.

Like thousands of other migrants, the 39-year-old Haitian man was stuck in Tapachula, trapped by Mexican immigration enforcement that has ramped up under pressure from the United States over the last several years.

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

Under Republican and Democratic administrations, the United States has pushed Mexico to stop migrants from getting anywhere close to its border. Mexico has obliged, sending its national guard to support immigration officials in its southern region.

Though many do still reach the U.S. border, asylum seekers who try to sneak out of Tapachula run the risk of ending up in Siglo XXI, a notorious immigration detention center and the largest in Mexico. They also could be deported to the countries they fled or expelled back to Guatemala.

As part of this pressure, the United States has encouraged Mexico to become a refuge rather than a transit country for asylum seekers. But conditions for migrants in Mexico are notoriously difficult. Often they become targets for assaults, kidnappings or worse.

With no other option, tens of thousands, including Denaud, have turned to the Mexican asylum system to request protection there, or to obtain documents with the hope of transiting Mexico more safely.

But receiving asylum in Mexico can complicate cases for those who do continue north to the United States, where they often feel safer and have loved ones to support them.

Asylum applications in Mexico more than tripled in the first nine months of 2021 from what they were in all of 2018. In 2019, the United States threatened Mexico with tariffs if the country did not stop migrants from reaching the United States.

The strategy worked. According to the Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados, the Mexican agency responsible for processing protection requests from migrants, commonly known by its acronym COMAR, about 70% of the people who asked for refuge in Mexico so far this year made the request in Tapachula.

“I think what we’re seeing down here in Tapachula is a clear example of externalization of the U.S. border,” said Andrew Bahena, who monitors human rights conditions at the Mexico-Guatemala border for the Los Angeles-based Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights, or CHIRLA.

Conditions in the border town are dire. Racism, xenophobia and lack of resources make it difficult for asylum seekers to survive while they wait for documents permitting them to travel out of the region.

After a grueling journey through Central America, Denaud found himself in Tapachula, asking COMAR to recognize him as a refugee because he saw no other option.

In 2015, he fled Haiti, where a combination of increased gang violence and kidnappings, natural disasters and a tumultuous political environment has caused an exodus over the past decade.

(The Los Angeles Times and the San Diego Union-Tribune are not fully identifying Denaud or other asylum seekers in this article due to their ongoing claims and vulnerable situations.)

Like many Haitians, Denaud ended up in Chile.

Then Chile began trying to force Haitians to leave by refusing to renew their permission to be in the country. Many Haitians, including Denaud, also experienced discrimination there from employers, neighbors, store owners and officials.

Despite all this, Denaud lost his asylum case in Mexico. He appealed, but the wait for a decision became unbearable as he felt more and more unsafe.

“When one flees danger, one enters into another danger,” he said in Spanish.

With the help of U.S.-affiliated attorneys, Denaud and his partner — a Salvadoran woman he met in Tapachula — were able to get an appointment to enter the United States and begin an asylum case there. That program no longer exists.

For migrants who arrived in Tapachula this summer, the situation was even more dire. Because of the increased demand, COMAR stopped offering appointments, the first step in Mexico’s refugee screening process, for several months.

That meant asylum seekers were stuck in southern Mexico without access to any system of protection, facing the potential of being rounded up by Mexican immigration officials or national guard and removed from the country.

The series of checkpoints and national guard patrols and slow processing of asylum claims have created what Bahena referred to as a “prison city.”

But the impoverished state of Chiapas lacks the resources to shelter everyone trapped there.

Migrants have tried moving together as groups, often referred to as caravans, to get out of southern Mexico, but have been violently halted by Mexico’s national guard.

What awaits them in the north might not be as much of an improvement as they hope.

Thousands have found themselves stranded along the U.S.-Mexico border under Trump administration policies, some of which, such as Title 42, have continued under President Biden.

Images of Border Patrol agents chasing down Haitian men in Del Rio, Texas, caused a similar public outcry to the reaction to videos of Mexican national guard treatment of Haitians earlier this year. Many of the Haitians who crossed into Texas that week ended up being expelled to Haiti.

Mexico’s southern border region has less economic opportunity and fewer resources to support new arrivals. The northern border is more expensive and where much of the violence against migrants occurs.

Olga Sánchez Martínez, who runs one of three migrant shelters in Tapachula, said she thinks the Mexican government’s strategies in the south are meant to keep more migrants from ending up stuck in its northern border cities.

“I don’t know what’s better for migrants, to be stuck there or to be stuck here,” Sánchez Martínez said.

For several months last summer, the Tapachula branch of COMAR stopped offering appointments to newcomers, meaning that asylum seekers could not start the process to request refuge in Mexico.

“We’ve never had so many people arriving at the same time,” said Andrés Alfonso Ramírez Silva, head of COMAR. “We were overwhelmed.”

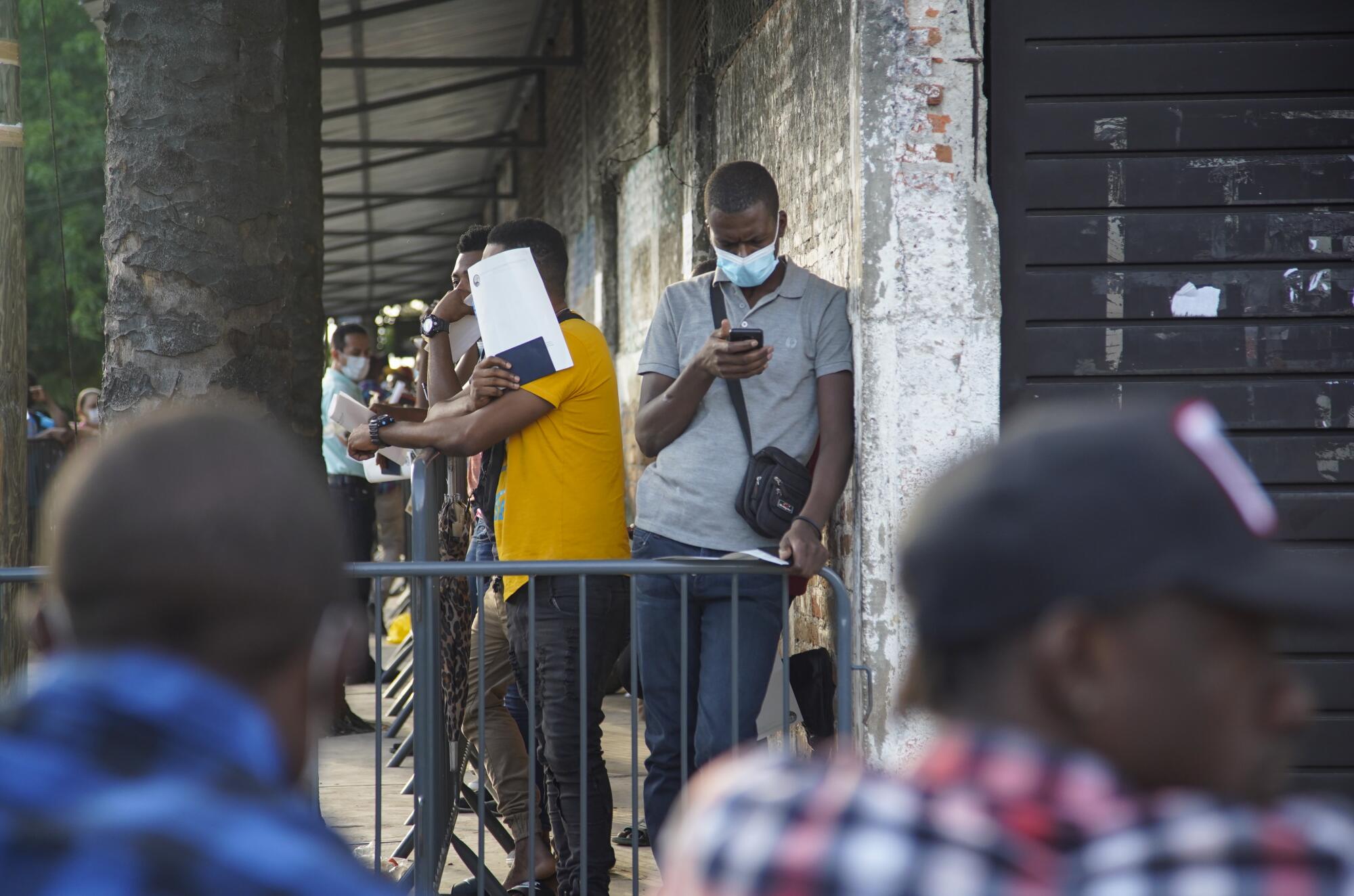

Hundreds gathered every morning outside one of the agency’s offices. Women passed by carrying plastic tubs of breads on their heads, calling out in Haitian Creole about the quality of their goods. Other street vendors peddled aguas frescas and snacks from tricycle carts.

“I come every day because they change the system, and... if you’re not there, then you don’t get an appointment,” said a Haitian man one late September morning.

The rules for winning asylum in Mexico are not the same as those of the United States. Mexico’s requirements to qualify are broader, opening up the potential for protection to a wider group of people.

In the United States, people requesting asylum must prove they fled their home because they were persecuted or feared being persecuted based on their race, religion, political opinion, nationality or membership in a social group such as the LGBTQ+ community. They have to show that that persecution is either by the government itself or by a group the government cannot or will not control.

Mexico adds gender-based persecution to that list of categories, and it also opens up protection to people who fled their homelands because of generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflict, major human rights violations or other circumstances that have seriously shaken public order — events that put the lives of residents at risk but don’t necessarily target individuals because of their identities.

Mexico’s overall grant rate for 2021 is about 74%, according to data published by COMAR.

As in the United States, that rate can vary widely from nationality to nationality. Hondurans, who make up the largest group of cases decided this year, were granted protection in 84% of cases. Haitians, the next biggest group, were granted protection in 29% of cases.

In the United States, asylum seekers who don’t have visas to enter the U.S. generally have their cases decided by immigration judges in a system that is marked by disparities and bias, as reported by the San Diego Union-Tribune last year. In Mexico, a series of appointments leading up to an interview with an official from COMAR determines whether someone qualifies.

After Mexico’s process in Tapachula broke down this year, COMAR asked those with appointments in the coming months to appear at Estadio Olímpico, a sports stadium, in late September to verify they were still waiting in the city to be processed.

Five weeks into the operation, Ramírez Silva said, COMAR had scheduled appointments with 41,000 people.

With so many asylum seekers stuck in Tapachula and only three shelters there that serve migrants, many struggle with finding places to live while they wait. Many sleep outside one of the shelters or even outside the immigration detention center.

“It’s not favorable conditions to live as a human being,” said Roel, a Cuban engineer seeking asylum with his wife and two children, of the place they were renting.

Outside the Jesus el Buen Pastor shelter, run by Sánchez Martínez, two young Nicaraguan men who fled the deadly Ortega regime waited one morning in late September to find out if they would be able to sleep there. The two crossed from Guatemala the day before and slept at a park.

The shelter initially housed amputees who fell from la bestia, the north-bound train that used to pass through the area. It expanded to meet the changing needs of migrants.

Capacity at the region’s newest shelter, Hospitalidad y Solidaridad, is low relative to the need.

Sánchez Martínez said her shelter could squeeze up to 1,000 people; Hospitalidad y Solidaridad can hold a maximum of 300, which it has halved during the pandemic.

The shelter, which receives funding from the United Nations refugee agency, known in Mexico by its Spanish acronym ACNUR, is only for people applying for asylum in Mexico or who have already been recognized as refugees.

It has a large courtyard with space for a sports court and a playground. The shelter hosts a soccer league to help migrants integrate into the community.

One Honduran family adopted a puppy they found on the street. The shelter approved as long as the family cared for Nina properly.

“They need a way to put the broken pieces of their lives back together now that they’re here in Mexico,” said Fernanda Acevedo, the shelter’s general coordinator.

At the northern border in Tijuana, many residents take in asylum seekers or bring food and other donations to where they are camped near the border. That type of aid isn’t visible in Tapachula, where attitudes about foreigners exacerbate the lack of support from locals.

“There’s a lot of misinformation,” Acevedo said. “That generates increased discrimination and xenophobia.”

Besides the struggles for food and adequate housing, there is an underlying question of safety for many of the asylum seekers forced to stay in Tapachula or in Mexico more generally.

Central Americans often feel unsafe because they are still close to their home countries, and their persecutors — gang members, abusive partners or otherwise — often appear in Tapachula looking for them.

Racism and xenophobia among residents and officials in the region make the city feel unsafe for many migrants, particularly Black asylum seekers. Some landlords even have rules against renting to foreigners.

Haitians in particular face racist treatment from Tapachula locals and officials. Even if they win asylum, they can still be targeted and forced to leave the country.

Johny, a Haitian man who was recognized as a refugee by Mexico, tried to take a bus to another city in southern Mexico to find work to support his pregnant wife after he received asylum. But Mexican officials took him off the bus and expelled him, he said. He had to pay a smuggler to cross him back into the country where he had refugee status.

“Now I am afraid,” he said in the Spanish that he learned during his time in Chile.

Witnessing the rampant racism in the area has been frustrating for Arturo Viscarra, an attorney with CHIRLA based in Tapachula.

“For Black migrants, I don’t think Mexico is a place for them, and it hurts me to say that,” Viscarra said. “You’re going to face a level of racism that — it’s a hazard. It’s dangerous.”

While migrants might feel they need asylum in Mexico in order to travel north safely, obtaining refugee status there actually makes their cases in the United States more complicated.

Asylum seekers who “firmly resettled” in another country before coming to the United States are not eligible for asylum unless they can show they also need protection from that country.

Those who obtained permission to stay in Mexico would have to prove that they didn’t actually resettle there or that they faced persecution in Mexico as well.

The legal community has been watching what will happen with the cases that do reach the United States since Mexican enforcement ramped up in the last two years.

Many asylum seekers don’t know that requesting protection in Mexico could complicate their cases in the United States.

Diop, a 34-year-old who fled political persecution in Mauritania, said he didn’t apply for asylum in Tapachula because he found out that it could affect his case once he reached the U.S., where he had family and friends waiting to help him in Colorado. He was stuck in Tapachula for about five months in 2019.

He and other asylum seekers from African countries staged a protest for months outside an immigration office, even sleeping in tents there to maintain pressure on Mexican officials to let them proceed north.

He said his experiences in Tapachula made him feel like he wasn’t a human being.

“We were beaten by the police, military police and the federal police, and we were prevented the freedom to travel,” Diop said. “I was desperate, but finally God decided that that situation get to be over and then to continue the journey.”

He went to Tijuana, but within a week found himself in danger there as well, facing death threats after witnessing a crime. He crossed the border in eastern San Diego and ended up at Otay Mesa Detention Center. He was able to get out on bond as the COVID-19 outbreak there began.

Now, he feels safer than he has for the past decade of his life.

He recently got approved to work in the United States while he waits for his case to proceed.

“You take all that risk trying to get to a safe place. You don’t worry about what you will experience during your travel,” he said. “The most important thing is to arrive to your destination and stay safe in that place.”

Second in an occasional series in which the Los Angeles Times and San Diego Union-Tribune explore Mexico’s role in migration and the conditions in that country that drive people north.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.