China’s nuclear and military buildup raises the risk of conflict in Asia

BEIJING — It was already a dangerous race: China versus the United States, each pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into missiles, submarines, warplanes and ships, vying to dominate the Indo-Pacific.

That race may now go nuclear.

A Pentagon report released this month estimated that China may have 700 nuclear warheads by 2027 and 1,000 by 2030 — a dramatic increase from last year’s assessment that China’s 200 or so warheads would only double over the next decade.

The Pentagon noted that China’s nuclear delivery platforms and supporting infrastructure indicate it may already possess a “nuclear triad” capable of launching missiles from the air, ground and sea. China may also be moving toward a “launch-on-warning” posture, it said, meaning it would have ready-to-fire missiles in response to an immediate threat, similar to the “high alert” postures the U.S. and Russia have had in place since the Cold War.

The sudden buildup of nuclear force suggests a possible change in China’s strategy from its traditional “minimum deterrence” stance to one that is tactically prepared for war.

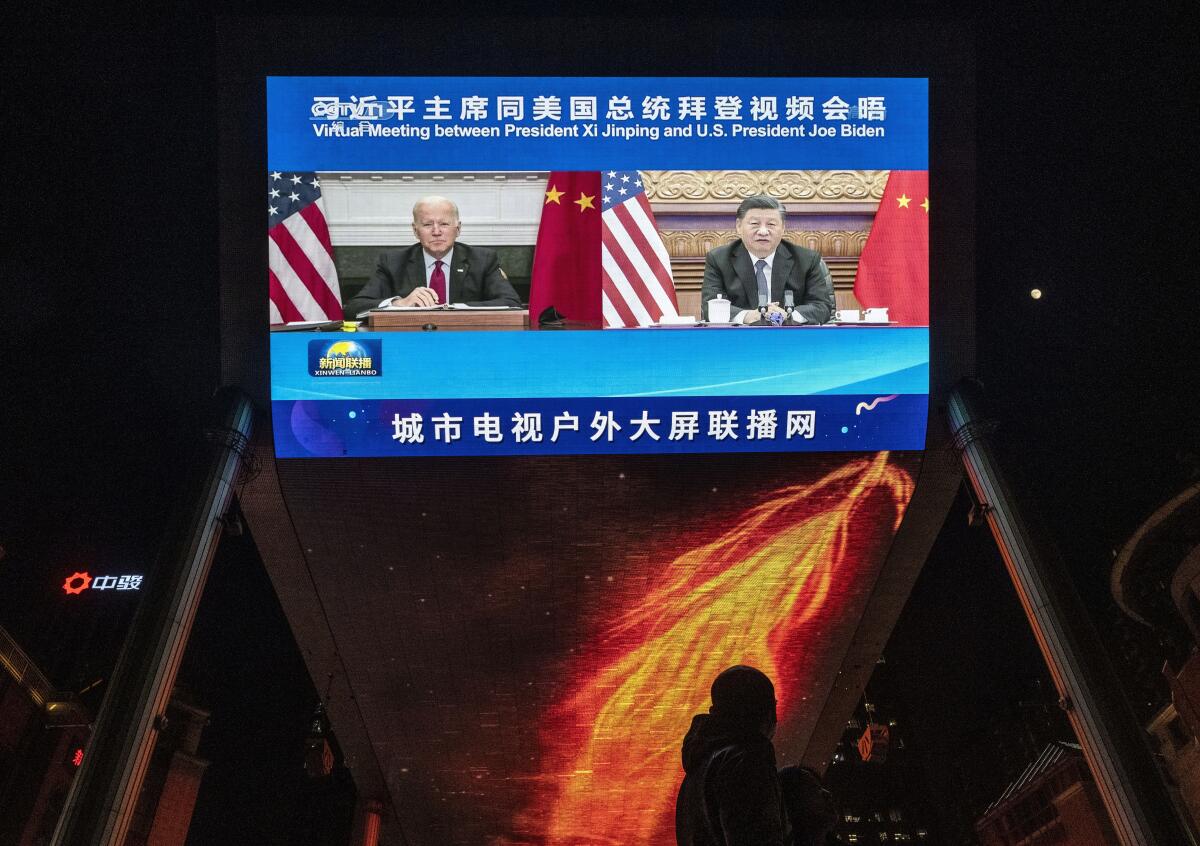

The shift comes as tensions between Beijing and Washington are rising over China’s recent reported test of a hypersonic missile and its more aggressive actions in the South China Sea and toward Taiwan. President Biden and Chinese leader Xi Jinping met in a three-hour summit this week hoping to ease the acrimony and suspicion between their nations.

A move away from minimum deterrence would be “totally contrary to everything I have ever read or talked about with the Chinese about how they think about nuclear weapons,” said Bonnie Glaser, director of the Asia program at the German Marshall Fund of the United States. “The U.S. and its intelligence is always worried when we get something wrong. And we clearly got this nuclear piece wrong.”

Beijing’s buildup is adding to a dangerous arms race across the Indo-Pacific. It is a setback for nuclear nonproliferation, which was already backsliding this decade, experts say, and raises the risks of conflict.

“The big picture is that there will be many more nuclear weapons on high alert, ready to launch at a moment’s notice,” said Hans Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, or FAS.

Kristensen is one of several independent experts who discovered through satellite imagery earlier this year that China is building at least three new nuclear missile silos in the deserts of Xinjiang, Gansu and Inner Mongolia. This silo construction constitutes “the most significant expansion of the Chinese nuclear arsenal ever,” Kristensen wrote in an analysis.

It’s not clear how China will operate the new silos or how many warheads each missile will carry. Despite its advances, China remains far behind the United States and Russia, which each have around 4,000 warheads and together hold 91% of all nuclear warheads, according to the FAS.

Still, the surprise growth of China’s nuclear arsenal is worrisome, experts said.

“People are nervous because they don’t really understand what Xi Jinping’s endgame is, what his strategy is, and how we can put in place some understanding or risk reduction measures to avoid conflict,” Glaser said. “And we have a history of knowing that when there’s a crisis, the Chinese don’t answer the phone.”

Analysts say China may have designed its expanding nuclear capabilities to defend itself as the U.S. strengthens its security alliances around the world. Beijing might still see its expansion as within a necessary “minimum” to keep up with perceived American threats.

“There is a growing sense of urgency at the top leadership level,” said Zhao Tong, a senior fellow in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy in Beijing. “It’s possible that Chinese leaders worry the U.S. is initiating a comprehensive campaign to destabilize China. In order to counter this perceived political hostility, China needs a stronger deterrent.”

The nuclear buildup may be an extension of Xi’s “strong military” vision — in short, that a great power should have a great military. Since taking charge in 2012, he has restructured China’s armed forces and set deadlines of 2035 and 2049 for the People’s Liberation Army to become a modernized and then “world class” military. China has about 975,000 active-duty personnel, according to the Pentagon report; its navy has 355 ships and submarines, the largest — if not most potent — fleet in the world.

China’s expanded nuclear capabilities would be viewed as a deterrent to the U.S. and its allies from intervening if China invades Taiwan, the island democracy that Beijing considers a breakaway province. Taiwan’s defense minister said last month that its military tensions with China were at their “worst in 40 years.”

Beijing flew 150 military aircraft over Taiwan’s Air Defense Identification Zone within five days in October, according to Taiwan’s Defense Ministry. These incursions have escalated as Taiwan builds stronger relations with other countries, welcoming delegations of European and American lawmakers to the island and acknowledging that the U.S. military is training Taiwanese soldiers.

Adm. Philip Davidson, head of the U.S. Navy’s Indo-Pacific Command, warned in March that China might attack Taiwan “in the next six years,” based on its rapid military expansion.

Xi told Biden at their summit on Tuesday that China prefers “peaceful unification” and does not seek conflict with the United States — but warned that “Taiwan independence separatist forces” and Americans who helped them were “playing with fire.” If they crossed a red line, China would take “decisive measures,” he said.

Some analysts have suggested that China could play a “shell game” with its new nuclear silos, in which it builds many but arms only a dozen or two of them. Kristensen said that seemed unlikely with so many under construction. “When countries build these large numbers of facilities, they tend to fill them.”

China’s military modernization was highlighted again this year when it reportedly tested a nuclear-capable hypersonic missile, which is launched into orbit on a rocket before detaching to glide toward its target, traveling five times faster than the speed of sound. Hypersonic missiles move on a lower trajectory than traditional ballistic missiles and can evade radar missile detection systems.

Gen. Mark A. Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, called the hypersonic missile test “very concerning” and “very close” to a “Sputnik moment.” The U.S. is also working on hypersonic weapons, but the Pentagon has not revealed whether China is ahead on that technology.

China’s Foreign Ministry denied testing a hypersonic missile. The ministry has not confirmed nor denied the reports on the nation’s overall nuclear expansion.

China is ahead of the United States in long-range missiles, in part because of a Cold War-era agreement called the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, or INF, which restricted the U.S. and Russia from having missiles with a range of 500 to 5,500 kilometers, or about 300 to 3,400 miles. China has deployed thousands of such missiles in recent years and fitted them on to warships and aircraft as part of a strategy focused on fending off a potential U.S. attack by sea.

Last week, satellite company Maxar Technologies released images showing that China has built models of a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier and destroyer in the deserts of Xinjiang. The U.S. Naval Institute said these models were probably being used for target practice by the People’s Liberation Army.

The U.S. pulled out of the INF under the Trump administration in 2019 and is now spending heavily on missile development to catch up specifically with China, which U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III has called the United States’ “No. 1 pacing challenge.”

These technologies will take years to build. In the meantime, the U.S. and China are in what analysts are calling a “dangerous decade,” where China may see a shrinking window of opportunity to seize Taiwan while it has a regional military advantage.

The Biden administration has sought to restore U.S. alliances as a way of countering China’s growing military might. The “Quad” group of the United States, India, Australia and Japan has pledged to protect a “free and open Indo-Pacific,” while the new AUKUS security pact among the U.S., U.K. and Australia promises to provide Australia with nuclear-powered submarines.

“The idea is to signal to China that the international community is vested in peace and stability. They’re not going to sit by if you use force,” said Glaser at the German Marshall Fund. “The world’s going to turn against you. You’re going to pay too high a price.”’

Biden’s efforts have also sparked anxiety in Beijing.

“The recent AUKUS deal is an alarm bell. It may make Beijing worry that time is not necessarily on China’s side,” Zhao said. “China may not be able to keep accumulating military advantage. So if it fears that window is closing, Beijing may think it is forced to do something.… The risk of a military conflict is very serious.”

The Biden-Xi summit aimed to ease diplomatic tensions and prevent accidental conflict. Unlike the Cold War, when the U.S. and the Soviet Union were largely isolated from each other, China and the United States are connected through their economies and global interests like addressing climate change. Military confrontation is not in either side’s interest.

The initial readouts after the summit indicated no change in either side’s views and no intentions to relax the arms buildup. But on Tuesday, U.S. national security advisor Jake Sullivan told an audience at the Brookings Institution in Washington that Biden and Xi had agreed to have “strategic stability” discussions around the nuclear issue. He did not specify a timeline or format for the talks.

It’s unlikely that Beijing and Washington can build trust when the friction between them is fundamentally ideological, Zhao said. “If they cannot have an honest and candid discussion about issues like the existence of basic universal values, I don’t see how they can mitigate their ideological confrontation and defuse tension.”

Some analysts dismiss the notion that China and the U.S. are sliding into a cold war. But Kristensen sees parallels. One side accelerates, the other side responds, and “suddenly you’re in this dynamic where everybody’s reacting to each other,” he said. “There seems to be no overall political plan. That is very much where we are now again.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.