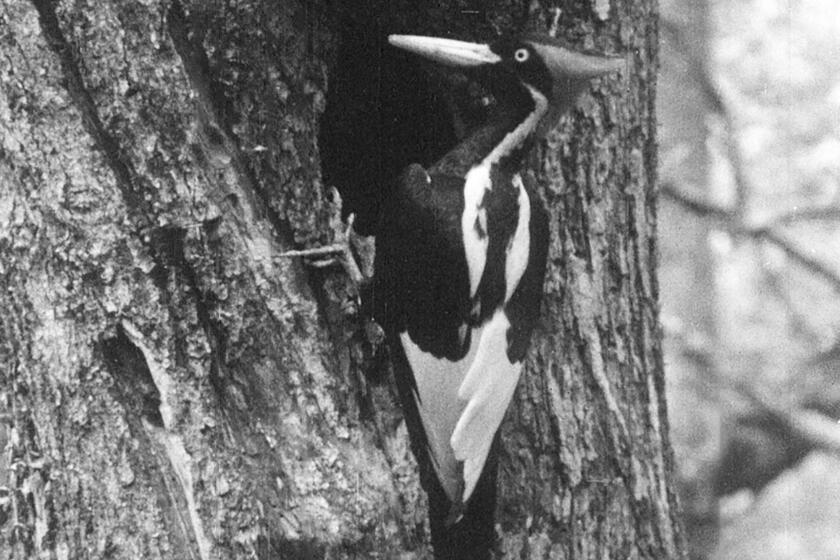

Ivory-billed woodpecker, 22 other species are now extinct, U.S. says

BILLINGS, Mont. — Death’s come knocking a last time for the splendid ivory-billed woodpecker and 22 more birds, fish and other species: The U.S. government Wednesday declared them extinct.

It’s a rare move for wildlife officials to give up hope on a plant or animal, but government scientists say they’ve exhausted efforts to find these 23. And they warn that climate change, on top of other pressures, could make such disappearances more common as a warming planet adds to the dangers facing imperiled plants and wildlife.

The ivory-billed woodpecker is perhaps the best-known of the species that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared extinct. It went out stubbornly and with fanfare, making unconfirmed appearances in recent decades that ignited a frenzy of ultimately fruitless searches in the swamps of Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Florida.

Other species such as the flat pigtoe, a freshwater mussel in the southeastern U.S., were identified in the wild only a few times and never seen again, meaning that by the time they got a name, they were already fading from existence.

“When I see one of those really rare ones, it’s always in the back of my mind that I might be the last one to see this animal again,” said Anthony “Andy” Ford, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist in Tennessee who specializes in freshwater mussels.

The factors behind the disappearances vary: too much development, water pollution, logging, competition from invasive species, birds killed for feathers and animals captured by private collectors. In all cases, however, humans were the ultimate cause.

Bad federal policy combined with an altered climate is wiping out California’s chinook salmon, plus more from the week in Opinion.

Another thing the 23 newly extinct species share: All were thought to have at least a slim chance of survival when added to the endangered-species list beginning in the 1960s. Only 11 species previously have been removed because of extinction in the almost half-century since the Endangered Species Act was signed into law. Wednesday’s announcement kicks off a three-month comment period before the species’ grim status change becomes final.

Around the globe, some 902 species have been documented as extinct. The actual number is thought to be much higher because some were never formally identified, and many scientists warn that Earth is in an “extinction crisis,” with flora and fauna disappearing at 1,000 times the historical rate.

It’s possible one or more of the 23 species included in Wednesday’s announcement could reappear, several scientists said.

A leading figure in the hunt for the ivory-billed woodpecker said it was premature to call off the effort, after millions of dollars spent on searches and habitat preservation efforts.

Dollars may flock to the area owing to its most famous resident: a bird unseen for 60 years.

“Little is gained and much is lost” with an extinction declaration, said Cornell University bird biologist John Fitzpatrick, lead author of a 2005 study that claimed the woodpecker had been rediscovered in eastern Arkansas.

“A bird this iconic and this representative of the major old-growth forests of the Southeast — keeping it on the list of endangered species keeps attention on it, keeps states thinking about managing habitat on the off-chance it still exists,” he said.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature, a Switzerland-based group that tracks extinctions globally, is not putting the ivory-billed woodpecker into its extinction column because it’s possible the birds still exist in Cuba, said the group’s Craig Hilton-Taylor.

Hilton-Taylor said there can be unintended but damaging consequences if extinction is declared prematurely. “Suddenly the [conservation] money is no longer there, and then suddenly you do drive it to extinction because you stop investing in it,” he said.

About one in six species now alive on the planet could become extinct as a result of climate change, according to a study published in Friday’s edition of the journal Science.

But wildlife officials said in an analysis released Wednesday that there have been no definitive sightings of the woodpecker since 1944 and “there is no objective evidence” of its continued existence.

U.S. officials said the extinctions declaration was driven by a desire to clear a backlog of recommended status changes for species that had not been acted upon for years. They said it would free up resources for on-the-ground conservation efforts for species that still have a chance of recovery.

What’s lost when those efforts fail are creatures often uniquely adapted to their environments. Freshwater mussel species like the ones the government says have gone extinct reproduce by attracting fish with a lure-like appendage, then sending out a cloud of larvae that attach to gills of fish until they’ve grown enough to drop off and live on their own.

The odds are slim against any mussel surviving into adulthood — a one-in-a-million chance, according to Ford of the wildlife service — but those that do can live a century or longer.

Unlike most of the nation’s great river systems, the Mobile Basin has survived with its rich biodiversity mostly intact. That is changing.

Hawaii has the most species on the extinction list: eight woodland birds and one plant. That’s in part because the islands have so many plants and animals that many have extremely small ranges and can blink out quickly.

The most recent to go extinct was the po’ouli, a type of bird known as a honeycreeper that was discovered in 1973.

By the late 1990s just three remained, a male and two females. After failures to get them to mate in the wild, the male was captured for potential breeding and died in 2004. The two females were never seen again.

The fate of Hawaii’s birds helped push Duke University extinction expert Stuart Pimm into his field. Despite the grim nature of the government’s proposal to move more species into the extinct column, Pimm said the toll would probably have been much higher without the Endangered Species Act.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“It’s a shame we didn’t get to those species in time, but when we do, we are usually able to save species,” he said.

Since 1975, 54 species have left the endangered list after recovering, including the bald eagle, brown pelican and most humpback whales.

Climate change is making species recovery harder, bringing drought, floods, wildfires and temperature swings that compound the threats already facing the species.

How they are saved is also changing. No longer is the focus on individual species, let alone individual birds. Officials say the broader goal now is to preserve their habitat, which boosts species of all types that live there.

“I hope we’re up to the challenge,” said biologist Michelle Bogardus with the wildlife service in Hawaii. “We don’t have the resources to prevent extinctions unilaterally. We have to think proactively about ecosystem health and how do we maintain it, given all these threats.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.