Stability in Israel, as Bennett reaches the 100-day mark

On June 13, Naftali Bennett did what many of his fellow citizens had come to believe was impossible, replacing Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s longest serving ruler, as prime minister.

Exhausted by two years in which four consecutive elections had proved inconclusive, and increasingly thirsty for stability, Israelis observed the political revolution with caution, fearing it might not last. No one was more dismissive than Netanyahu, who assured fellow lawmakers attending the new government’s investiture that “in two to three months this thing is breaking up.”

Yet to the surprise of friend and foe alike, 100 days later it appears that former Netanyahu aide Bennett, 49, has managed to keep together his unlikely rainbow coalition. Heading an improbable alliance that stretches from the socialist-leaning Meretz party, a champion of gay rights, to the United Arab List, an Islamist party affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, Bennett appears to be sailing smoothly toward the next important milestone, passage of a national budget in the first half of November.

As Bennett prepares to celebrate his 100th day as prime minister Tuesday, merely having replaced Netanyahu has proved a major shift. “Removing Netanyahu is this government’s mission,” said Afif Abu Much, a prominent political analyst.

“People have simply forgotten what we’ve liberated ourselves from,” said Ehud Barak, a former Labor Party prime minister, referring to the disorderly final years of Netanyahu’s premiership. During that time, Netanyahu was indicted on criminal corruption charges and embarked on what critics viewed as an all-out assault on Israeli institutions, including the suspension of the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, in March 2020, and his attempt, in April 2021, to install a crony as minister of justice, an action overturned by the Supreme Court.

Still, some who agree with that assessment believe much more should change.

“If the aim was to remove Benjamin Netanyahu, that has been achieved,” said Ahmad Tibi, a veteran legislator for the majority-Arab Joint List party and a left-wing activist for Palestinian statehood who now finds himself in a peculiar parliamentary pickle: seated on the opposition benches alongside his archrival Netanyahu.

“The real question is whether policy has changed. From our point of view, no,” Tibi said in an interview. “Not for the Arab community, not for Gaza, West Bank settlements continue to grow, there is no peace process. No change.”

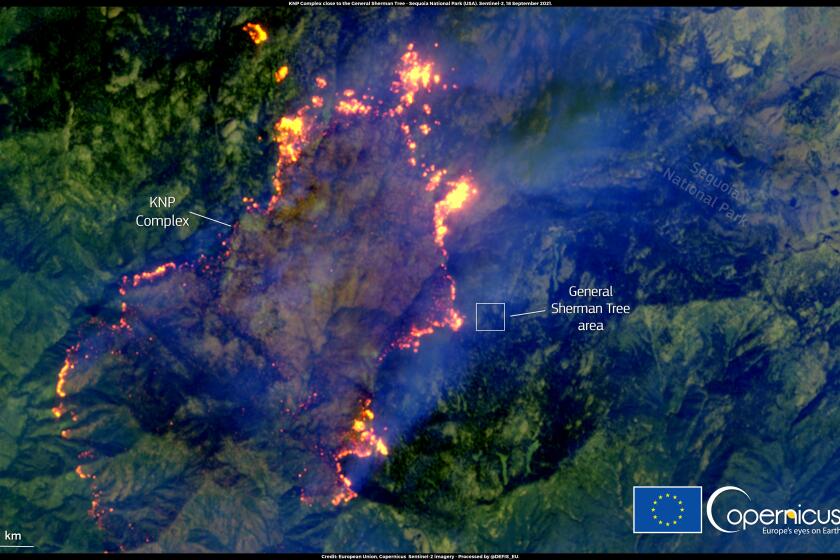

The KNP Complex fire in Sequoia National Park grew more than 3,900 acres overnight, but firefighters have kept key areas under control.

For now, it may be difficult to separate Bennett from his predecessor because the entirety of Bennett’s eight short years in Israeli electoral politics has taken place under the shadow of Netanyahu’s dominance. For most of this time, Bennett was best known as a sort of amiable extremist, a leader of the West Bank settler movement who denied the right of Palestinians to an independent state, nipped at Netanyahu from the right, dressed in polo shirts and jeans, and lived in a classy suburb of Tel Aviv.

Hints of a different, less strident Bennett emerged from rare accounts from those who knew him from his pre-political early years as a startup impresario. In 2013, when Bennett won his first legislative seat, his business partner Lior Golan, a moderate who did not vote for him, said that Bennett’s “dream was to reenact in politics what he did at Cyota — which was a team working in unison toward a certain goal, without internal politics, for mutual success.” Cyota was the startup Bennett founded with three friends, and sold, in 2005, for $145 million in cash.

While Bennett’s government may yet find itself mired in paralysis, the description of a team of technocrats working toward a common goal matches in many ways the coalition he currently leads.

“Preserving the nation’s democratic equilibrium prevailed over partisan political objectives,” former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, who served from 2006 to 2009, said in an interview about Bennett’s government, which he hailed as “a return to normality.”

Barak, who shares little common political ground with Bennett, said that “for many of us, there is a real sigh of relief. You no longer hear a prime minister alarming citizens of a very powerful state about imagined demons abroad and traitors within.”

At the same time, Israeli media appear to be having trouble letting go of Netanyahu. On Sept. 15, numerous Israeli outlets reported on the first anniversary of the Abraham Accords, the normalization agreements between Israel, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan, brokered by the Trump administration, by headlining the fact that Bennett did not mention Netanyahu in his formal remarks.

Yet for those with long ties to Bennett, his ambition and his success, thus far, as prime minister, are not surprising. Yohanan Plesner, the president of the Israel Democracy Institute, a non-partisan Jerusalem think tank, has known Bennett since they served together in Sayeret Matkal, the Israeli army’s most elite unit. Later, they became friends while studying at the Hebrew University. A few years after that, Plesner found himself sparring with Bennett when they served as young aides to Netanyahu and to Olmert, respectively.

Plesner described the Bennett he knew in the late ‘80s as “an alpha male, a leader, very entrepreneurial, but also a guy who really listened and was genuinely interested, who took nothing for granted. He was always trustworthy, a pragmatist, with his feet planted firmly on the ground.”

A generation before them, Netanyahu had also been an officer in the same fabled unit. The difference between the two leaders, Plesner said, is that to this day, Bennett’s “team loves him. Same goes for him. They may not agree on politics, but he sees them as patriots, they’re his brothers in arms. There’s no hate.”

Bibi, on the other hand, he said, using Netanyahu’s ubiquitous nickname, “nurtured a grudge that just grew and grew against anyone who didn’t agree with him.”

In Plesner’s view, Bennett’s difficulty in establishing a public persona arose from conflicting traits: on the one hand, a true believer in the hard-line politics he represents, but on the other, a “natural uniter.”

The new Israeli government has gained accolades for its rollout of the COVID-19 booster shots, which appears to be diminishing rates of the Delta variant, for Bennett’s successful White House visit in August and ceremonial summit with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah Sisi, and for renewed diplomatic initiatives toward Jordan and Persian Gulf states.

While Netanyahu, who will turn 72 in October, has not yet succeeded in gaining traction as opposition leader, the specter of his political return is credited with bolstering Bennett. In a positive assessment of Bennett’s first 90 days in office, the Haaretz daily said, “World leaders are empowering him, showering prestige and legitimacy on him, because his predecessor’s return to power is their nightmare. It’s hard to blame them.”

Relief at restoration of conventional diplomacy and regular political process is a common theme among Israeli political observers, even those, like Barak and Olmert, with deep apprehensions about Israel’s predicament.

Topping the list of Israel’s security concerns is Iran’s nuclear program, where, according to retired Gen. Amos Yadlin, “Netanyahu left Bennett a very difficult bequest.” Iran’s race to enrich uranium since the United States, encouraged by Netanyahu, abandoned the multi-national nuclear treaty in 2015, “would force any Israeli prime minister to make some very difficult decisions,” said Yadlin, who recently retired as executive director of the Institute for National Security Studies.

One hundred days, Yadlin said, “is a period of time in which mostly, you shouldn’t make any mistakes, but you don’t yet have anything to show off about.”

But he praised the “change in spirit, the different music, the feeling of trust” engendered by Bennett in the face of numerous challenges.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.