MILWAUKEE — Jeremiah Hughes was mowing a lawn on a Wednesday afternoon when two men barged through an alley gate. They were armed. Shots rang out.

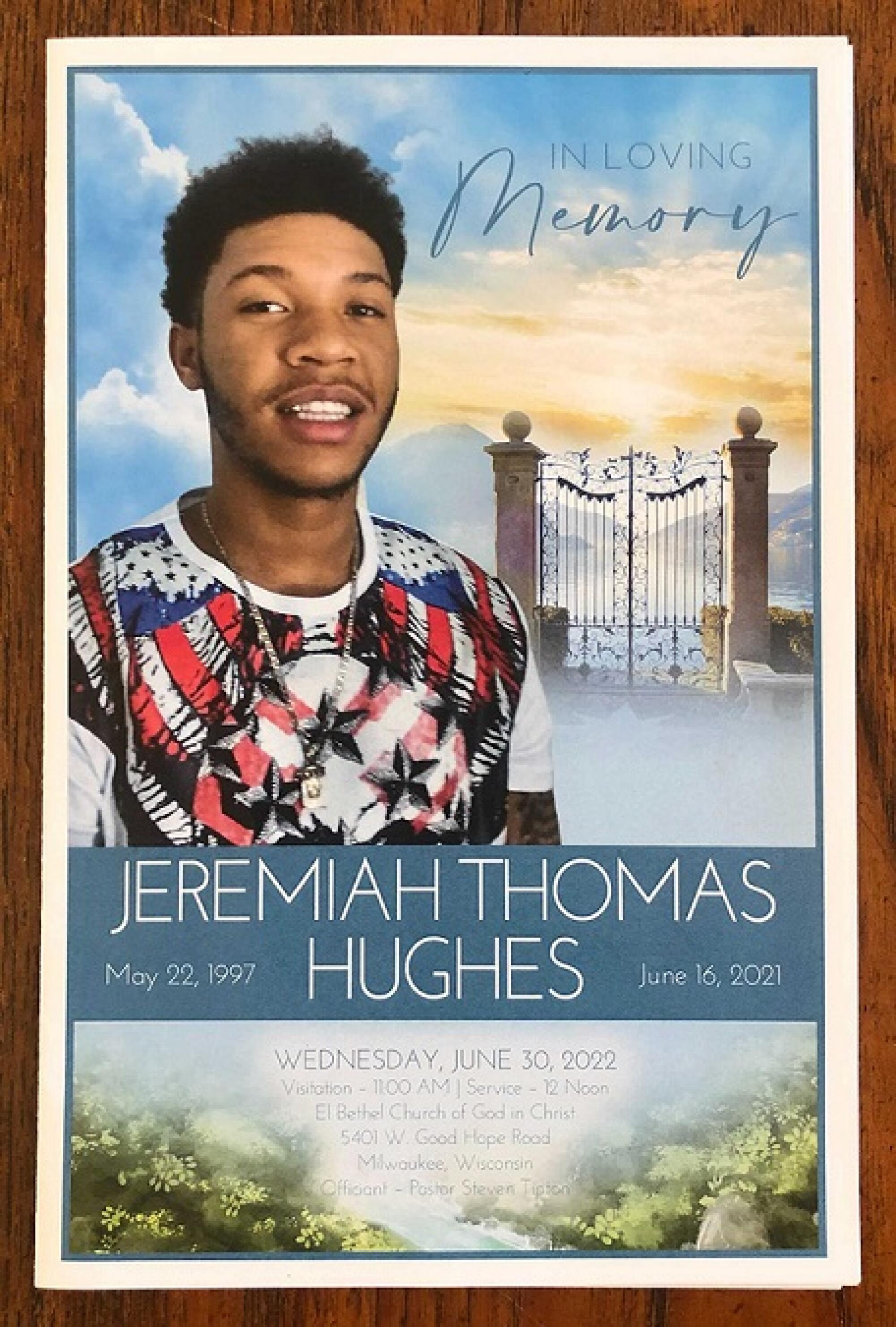

Hughes died in the yard and was taken to the morgue and then to El Bethel Church of God in Christ, where days later he lay in an open, emerald-green casket as muffled cries rose through a hymn on a loudspeaker. He was 24 and had his mother’s name — Gwen — tattooed on his left hand.

Velvet ropes surrounded his casket to prevent people from grabbing for him in their despair.

“My only son,” said his father, Stan Lindsey. “Gone like that.”

Milwaukee is in the grip of the worst violence in its modern history. There were 189 killings here last year, a 93% increase from 2019 and the most ever recorded.

The jump reflects a nationwide trend. In one study, researchers from the nonprofit Council on Criminal Justice looked at 34 cities and found that 29 had more homicides last year than in 2019. The overall rise was 30%, though in most places killings remained below their peaks in the 1990s.

Among the 19 cities with more than half a million people — including Los Angeles, New York and Chicago — none saw a bigger surge than Milwaukee. With 127 killings through the first half of September, the city is nearly on pace to match last year’s record. Hughes was the 78th person killed this year.

The uniformity of the nationwide rise has launched multiple theories about what is driving it. Nearly all center on the pandemic — which has caused enormous hardships — and the mass movement against police brutality and racism, which changed policing and the relationship between law enforcement and communities where violence has long been concentrated.

Did a society on edge, with schools closed, social programs shut down and people cramped up at home, simply become more violent? Were more people carrying guns? Did police retreat in a way that emboldened criminals? Experts say it could take years to unravel those questions, but the toll of the fallen has struck hard in neighborhoods across the country.

There are no clear answers in the June 16 killing of Hughes. Police have released only basic details from their investigation: The weapon was a “long gun,” the motive “retaliation,” and the two suspects were “acquaintances” of Hughes, who had no criminal record.

Lindsey said he believes the intended target was a young man who worked for Hughes on landscaping jobs and had a feud with the suspects. The gunfire missed the employee. Nobody has been arrested in the case.

The violence in Milwaukee follows familiar patterns, according to the city’s Homicide Review Commission.

In a city that is 40% Black, most victims are Black men, as are the perpetrators, who usually kill with handguns.

Most of the homicides last year — 54% — occurred in a roughly 30-block radius on the north side, a predominantly Black area where deep-rooted racism has led to neglect and poverty.

What’s different now is that many more people are dying.

Donnell Dunbar, 27

Dayleon Groves, 19

Jovan Wilder, 18

Corey Tucker, 36

Yosef Timms, 32

The list of young Black men shot and killed on the north side goes on and on. Hughes was one of them, and he was a child of the neighborhood before he was a statistic.

::

The phone at the New Pitts Mortuary on the north side was ringing nonstop.

Michelle Pitts was used to it — COVID-19 was devastating the Black community she serves. Her staff of a dozen worked nearly around the clock. More than once, Pitts sat alone in her wood-paneled office and cried.

COVID-19 mostly claimed senior citizens. But around July 2020, Pitts started getting more calls to arrange funerals for young men who had been shot.

Nobody knew it, but the city was starting to face another epidemic — one concentrated in a neighborhood Pitts knew well.

Her parents had settled here in the 1950s after leaving Arkansas — part of the Great Migration of African Americans fleeing racial terrorism in the South for the hope of better lives in the industrial cities of the North.

The neighborhood was the only option for most Black families, because deeds excluded them from renting in other parts of the city. Redlining by banks, which automatically disqualified people in Black neighborhoods from taking out mortgages, made homeownership a distant fantasy.

Residents were also denied adequate healthcare and education. When Interstate 43 was constructed through the area in the 1960s, businesses were demolished.

Despite the racism, Pitts recalls a neighborhood that felt safe — a place where killings were so rare that safety never crossed her mind. As in many cities, drugs in the 1980s quickly changed that.

Homicides started to climb, and so did a sense of despair. In one ZIP Code here — 53206 — 42% of people now live below the poverty line, among the highest rates in Wisconsin.

Families that could afford to leave the north side did so. Pitts moved to a nearby suburb in the early 2000s, a few years after her husband died and she took over the funeral home he had started.

The gray stone building sits on a street lined with Victorian houses and corner stores and gas stations where some residents purposely fill their cars in the mornings, when the chances of getting shot seem lowest.

Since the pandemic began, the funeral home, which has room for 35 bodies, has rarely not been full. It’s more death than Pitts has ever witnessed.

“We now had COVID deaths and literally children and young people dying in the streets,” she said. “What I have seen with these murders — tragic murders — is unlike anything I’ve ever seen in my work.”

She has handled more than a dozen homicide funerals since January — the emotional toll making it hard for her to keep count. “Two homicide funerals feels like 10,” she said.

She suffered heartbreak of her own this spring when her granddaughter died in a car accident; she found solace in a grief support group she formed this year for the families she serves.

“I’m not alone in this sense of hopelessness,” she said. “It’s just that everyone has gone through a lot with COVID and now this.”

Hughes was a part of “this,” another young man whose family was ordering a casket and providing Pitts details about a short life. His middle name was Thomas, and those closest knew him as Tommy. He was gregarious. He enjoyed music. He loved working with his hands. He was optimistic. He loved to talk about God.

During the funeral service for Hughes, Pitts watched from the back of the church and wondered: How can things change?

She mused that public shaming could be part of the answer. Images of convicted killers could be displayed on billboards. It was a stretch, but it was something.

Each day on her way home, Pitts drives past playgrounds that are nearly empty because parents worried about stray bullets keep their children bunkered inside.

She will return to the north side the next day, ready for what awaits.

::

Inside a conference room in the homicide unit of the Milwaukee Police Department in July, notes scrawled in green marker on a whiteboard offered details about a recent north side slaying.

“GSWs” — gunshot wounds — “mid-lower back, testicle, right foot, right knee. Casings: 5.”

It was among dozens of active cases.

“It’s been draining,” said Det. Mike Washington, 46. “And it’s almost nonstop.”

Washington was born in Chicago but moved to Milwaukee when he was 12. His family lived on the northwest side, another area that has suffered neglect. His mother was a nurse and his stepfather supervised janitors.

He was in his early 20s and working at a bank when a friend mentioned that the Police Department, which was facing political pressure to diversify, was looking for Black recruits. He signed up on a whim, part of a hiring spree that rapidly transformed the force into a racial mirror of the city.

After five years on patrol and several more as a detective assigned to vice and violent crime, Washington joined the homicide unit in 2014. That year, the team of 36 detectives investigated 87 homicides.

“It was manageable,” he said.

As much as he disliked delivering tragic news to families, Washington found his work deeply meaningful.

Then, in 2017, it became deeply personal. His sister, Sherida, was murdered by her husband, a fellow police officer, who then turned the gun on himself.

From then on, Washington began counting down the days until July 29, 2021, when he would be eligible for retirement.

The pandemic year became his final test.

Like much of his unit, he eventually got COVID-19 — and then recovered. Then there were coronavirus precautions, such as the elimination of live lineups from which witnesses identify suspects, making it harder to clear cases.

More significantly, the rising caseload began to overwhelm the unit.

In 2019, there was an average of eight homicides a month. The first sign of an uptick in 2020 came in February — before most people were paying any attention to the coronavirus — when there were 18 killings.

But the upward trend didn’t become clear until July, amid nationwide protests after the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police. As in many cities, that summer and fall in Milwaukee grew much more deadly.

Washington and the unit were stumped about the causes, though they noticed that more killings seemed to involve people under 18. Twenty-seven victims and 13 suspects last year were minors, up from eight and four in 2019.

That aligned with schools being shut down. Still, it could only account for a small portion of the overall rise in homicides.

Much clearer was that more people were carrying guns. Milwaukee police confiscated more than 3,000 last year during traffic stops and domestic dispute calls — an 18% increase from 2019 — and officers have continued to recover guns at the same pace this year.

“People have little patience with one another,” Washington said. “There’s a fight and automatically a gun comes out.”

Another possible factor was the protests. Milwaukee was no stranger to police violence — many people were still angry that an officer who killed an unarmed Black man in 2014 was never charged with a crime — and the national reckoning seemed to worsen tensions between police and the communities they were sworn to protect.

Washington noticed a slight drop-off in calls from his contacts on the north side.

One of four Black detectives in the homicide unit, Washington would listen as some of his white colleagues complained about the demonstrators.

“Some would gripe about, ‘Where are these protesters when people get killed daily here in the city?‘” he said.

Washington understood how they felt — he believed most police were honorable — but he also believed some lacked empathy. Black officers now make up 18% of the force, which has downsized considerably over the last two decades and become much less diverse. The homicide unit has shrunk to two dozen detectives.

At times, Washington felt wedged between two worlds. He was a veteran cop. But he was also a Black man from the community, which helped him defuse tense situations at homicide scenes, where investigation protocols meant that bodies sometimes remained in the street for hours, even if it upset families.

“I tried to make a connection, limit the chaos at scenes because of emotions,” he said.

When his retirement date finally arrived, Washington was ready to go — too often he had seen the bodies of Black men curled up on the streets, too often he’d interrogated other Black men about the deaths.

His department gave him a signed poster board commemorating his service and a gold watch.

On his final shift, he sat alone at his desk near a window where boxes were stacked with his belongings. All around him detectives typed away at keyboards, trying to reduce the backlog.

::

The logjam of cases includes the killing of 18-year-old Winfred Jackson Jr., whose body was discovered the night of March 17, 2020 — just as pandemic lockdowns were beginning.

Police who arrived at the north side house where he lived with his older sister, Jalisa Martin, told her what they knew. ShotSpotter — a system that uses acoustic sensors around the city to detect gunshots — had led them to nearby Washington Park.

They followed a trail of blood to a tiny lagoon. Jackson’s body was floating in the water. He had been shot multiple times, the 28th homicide victim of the year.

Martin, 32, struggled to make sense of it all. Her little brother was preparing to get his GED at an alternative high school. He dreamed of joining the Army — of leaving Milwaukee and seeing the world.

In the weeks leading up to his death, Jackson told Martin he had been involved in a fight with teens from his school. Police informed her that DNA evidence was found under his nails — indicating a scuffle — but that it produced no matches.

Detectives called Martin every few days, asking questions.

Did your brother have a beef with anybody? Just the fight he told her about.

Who had he hung out with recently? Some friends from high school.

Did he ever express concerns about anyone? No.

“It seemed like they were really invested,” she said. “They wanted to catch who killed him.”

But as the pandemic worsened and the homicide toll rose, the calls became less frequent. Some time last summer, they stopped.

Her brother’s killing has been turned over to the cold case unit.

Milwaukee police have solved 58% of the homicides committed last year, down from 68% in 2019. The rate so far this year is 34%.

Martin, who works as an in-home nurse, carries a stack of Crime Stoppers fliers offering a $1,000 reward to anyone who can help solve the case, taping them to light poles in the neighborhood.

“His family needs answers!!!” it reads. “Winfred deserves justice!!!”

Sometimes she visits Washington Park and stares at the piece of tattered, yellow police tape still hanging from a chain-link fence near where her brother was killed.

They were close as kids. Even though he was always tall, she called him “Little Win.”

She tries her best to remember the sound of his voice singing in the church choir as kids. Or how he would lift her young son and daughter over his shoulder and spin them around her living room.

“I just wanted justice for my brother — that’s all,” Martin said. “Some sort of justice and for these killings to stop.”

::

The Milwaukee Bucks had just won the 2021 NBA championship on July 20 when the pager Tonia Liddell wears on a lanyard around her neck beeped three times.

Female, 19 years old.

Male, 22 years old.

Male, 32 years old.

All had been wounded near a downtown corner in a pair of shootings after midnight during the victory celebration. They were being rushed to Froedtert Hospital.

Liddell, 46, is what’s known as a “violence interrupter.” Her job is to counsel gunshot victims and their families in hopes of heading off retaliation killings.

She got into the work in 2005 after her 16-year-old godson was shot and killed while he and his girlfriend were sitting in his car on a north side corner.

Programs like 414LIFE — Liddell’s employer — are widely credited with reducing homicides. Liddell learned over the years that success depends on making connections in the first few days after a shooting, when emotions are highest.

That often means knocking on the doors of grieving families and friends or visiting shooting victims in hospital beds. She connects them with mental health services or jobs programs, or just sits with them to pray.

“I always tell them that I am so blessed to be able meet them,” she said. “We are all blessed to have this new moment, this new opportunity.”

At least that’s how it all worked before the pandemic. When the shutdowns began — just as Liddell lost her mother to COVID-19 — her job went virtual.

Those in-person meetings became FaceTime conversations facilitated by hospital staff.

“It didn’t matter how we did it, we just need to be sure we were making connections,” she said.

But at times she felt the separation wasn’t cutting it. Too often families were declining her calls.

Before long, the video of Floyd’s murder was playing across the country and the lockdowns entered their third month. People were growing increasingly exhausted and began leaving their homes.

“What we saw was a lot of built-up frustration. Stress from the pandemic, anger and a deeper distrust of police,” Liddell said. “It all exploded in the streets.”

Her pager wouldn’t stop buzzing. Milwaukee saw 752 nonfatal shooting victims last year — a 69% increase from 2019 — and 586 more in the first eight months of this year.

Liddell sometimes wondered which killings she might have prevented had she been able to track down people in person.

She finally got the chance this spring. With COVID-19 vaccination rates rising, Liddell now routinely visits shooting scenes and hospital rooms.

She rarely gets more than a day off at a time, the calls coming so frequently that sometimes she has no choice but to leave her daughters, 11 and 14, waiting in the back of her SUV.

Lately, Liddell and her colleagues have been seeing more teenagers who were shot after arguments that began on social media.

Parents forward Instagram or Facebook Live posts of young men flashing firearms and threatening each other.

“That’s where we can make a difference. We go to the neighborhood,” Liddell said. “Sometimes we are straight up and tell the kids we saw the video and ask, do they want to end up dead? ... But we look to engage, talk, see what’s really going on.”

The three people who were shot after the Bucks won the championship all survived. But only one agreed to speak with Liddell.

::

A few weeks before Jeremiah Hughes was killed, his father told him he was going to help pay for a new pickup. Hughes was eager to expand his landscaping business, and Stan Lindsey wanted to support him in any way he could.

Lindsey enjoyed watching his young boy grow into a hardworking young man with a girlfriend and deep love for his large family. He had seven siblings and step-siblings.

Now, Lindsey stared at his son’s casket as Steven Tipton, the pastor at El Bethel, approached the pulpit and began to speak.

He told the dozens of mourners that he’d officiated several services for homicide victims recently and noted a pattern. Many had started as tiffs on social media or other disputes that once would have been settled with words.

“Then you see bullets fly,” he said.

Midway through the service, as Tipton stood silently for a moment, a young man rose from his seat.

“They killed my uncle!” he shouted through tears. “I’m gonna kill them!”

Tipton looked down at the lectern thinking about how to respond. Sobs grew louder.

“This is senseless, this is not normal,” Tipton finally said, his voice beginning to boom. “This city must do better.”

“Yes! Yes!” a woman shouted from the front. “Amen, yes!”

Times staff writers Richard Read in Seattle and Terry Castleman in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.