For many Texans, it’s a long drive out of state for abortion

WICHITA, Kan. — Of the 25 patients who showed up at the Trust Women Wichita clinic in Kansas for abortions Thursday, 10 drove hundreds of miles north from Texas, traveling farther and at greater cost because of a new law in the Lone Star State that in effect banned abortion, dramatically expanding the nation’s largest “abortion desert.”

Outside the clinic, several antiabortion protesters lingered with a doll set up in a baby swing, trying to hand pamphlets to women as they drove into the parking lot already full of vehicles with Texas license plates.

Meagan, who asked to be identified only by her first name, said she traveled to the clinic from Texas after receiving a positive pregnancy test the day the law took effect, Sept. 1. She was already beyond six weeks pregnant, which generally coincides with the limit set by the new law.

“The timing could not be worse; I missed the window,” said Meagan, 36.

While some Texas women can afford to fly farther afield — and more already are traveling to California — most drive to neighboring states for abortions. Trust Women expected to see just as many Texas patients Friday at its clinics in Wichita and Oklahoma City, which have booked appointments into October. Staff members were unsure what will happen after that.

The Texas “heartbeat law” was designed to ban abortion when fetal cardiac activity can be detected, usually around six weeks. Texas’ governor is set to sign another law banning the mailing of abortion medication and distribution to those more than seven weeks pregnant.

In Oklahoma, a “heartbeat law” similar to the one in Texas is set to take effect Nov. 1. Kansas lawmakers put an antiabortion amendment to the state constitution on the ballot next year.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott said the law gives women six weeks to seek an abortion. But that’s not really true. Here’s the biological reality of the challenged legislation.

The U.S. Supreme Court declined to block the Texas law but plans to consider a Mississippi case challenging the landmark Roe vs. Wade decision next month, with a ruling likely by June that could allow antiabortion laws to take effect in half the states.

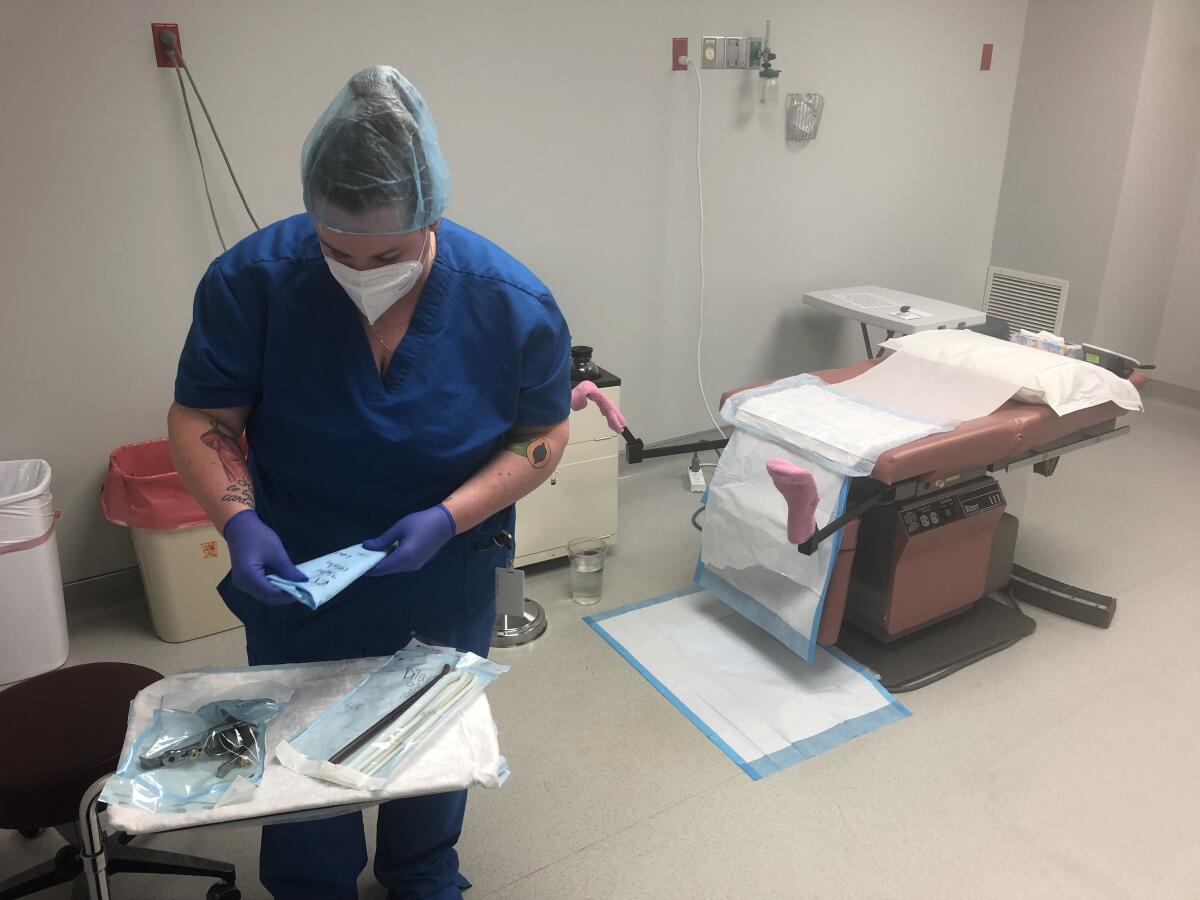

“A lot of people are looking to this clinic as a haven,” said Ashley Brink, director of the Wichita clinic, which is adding staff members and supplies and renovating to serve more Texas patients. “They have all of these questions; they’re scared and confused; they don’t know what’s going on.”

Trust Women saw a similar influx of out-of-state patients last year, when the governors of Oklahoma and Texas suspended abortions as elective procedures during the pandemic (the courts ultimately reversed them). But Texas’ abortion ban is the most restrictive enacted since Roe vs. Wade was decided in 1973.

More than a dozen mainly Southern states have passed “heartbeat laws” similar to Texas’, but most have been blocked by the courts. The Supreme Court declined to block the Texas law in part because those who crafted it left enforcement not up to the state but to individuals, who can file lawsuits for a minimum of $10,000 against those they suspect of obtaining or “aiding and abetting” those seeking abortions in Texas.

The Justice Department sued to block the Texas law, which makes no exceptions for incest or rape, requesting that a federal judge issue a temporary restraining order.

“Many patients have already been forced to travel hundreds and sometimes thousands of miles to obtain an abortion out of state,” the Justice Department said in its request, including “a minor who was raped by a family member and had to travel eight hours from Galveston to Oklahoma in order to obtain an abortion.”

But on Thursday, the federal judge in Austin refused to rule ahead of an Oct. 1 hearing on the restraining order.

Neesha Davé, acting executive director of the Austin-based Lilith Fund, which helps women pay for abortions, said the restraining order would be “a really helpful tool to protect our programs from being hurt by these harassing lawsuits by antiabortion vigilantes. But it’s not the big relief people need so they can access abortion in their home state.”

Meagan looked tired, wearing a Bob Marley T-shirt, sweatpants and sandals, her light brown hair loose around her shoulders. She said she worried that the Texas clinics she consulted might get her in trouble under the new law. When she asked the staff at one of the clinics where she could get an abortion out of state, she said they told her they couldn’t help. When they called to find out where she was going, she stopped answering.

“I cut off all contact with those clinics when they continued to ask what my plans were,” Meagan said, her voice raspy from morning sickness. “Is your name going to be reported? You don’t know. It’s still a new law.”

She had a surgical abortion years ago in Dallas that was painful and this time wanted abortion medication. But that’s available only up to 10 weeks.

She found out clinics in Oklahoma were booked until mid-October, and clinics in Louisiana had closed after losing power because of Hurricane Ida. Meagan said she worried Arkansas clinics might be dangerous given the political climate. So she traveled to Kansas for the first time in her life, driving nine hours overnight and staying at a hotel.

Clinic staffer Melissa Tovar was used to stress: The fenced Wichita clinic has drawn crowds and even closed for several years after its director, Dr. George Tiller, was fatally shot by an antiabortion extremist.

But now she’s fielding calls from increasingly desperate Texas women trying to schedule abortions, some already in their second trimester. She’s had to refer some to clinics in Colorado and New Mexico, which allow abortions later in pregnancies than Kansas.

“There’s just not enough clinics to support the women who need us, and this law has made it harder,” said Tovar, 42, adding that when she had an abortion at age 18, she got an appointment within a week at a since-closed clinic in her hometown of Lawrence, Kan.

The Texas law increased the average one-way driving distance to an abortion provider from 17 miles to 247 miles, according to the Guttmacher Institute, which researches reproductive health policy. The average driving distance to one of California’s roughly 160 clinics: three miles.

When Meagan arrived at the Wichita clinic, antiabortion protesters tried to intercept her near the driveway. She ignored them. She’s had three previous miscarriages, and with each pregnancy suffered medical problems: hemorrhaging, anemia, chronic fatigue and nausea. She said she decided to have an abortion “for my own health.”

She said she got pregnant after having sex with a friend, who has been supportive. He contacted clinics; helped her make the appointment; drove; and paid for the hotel room, abortion pills and other travel expenses. Total cost: about $1,000.

Meagan works as a bartender and said her boss was also sympathetic, giving her sick leave. She earns about $34,000 a year and was in the process of moving; she also just had to get a new car and pay $300 to take her dog to the vet. She’s been homeless before, lived out of her car and knows there are other women in that position now.

“There’s people that can’t travel, that can’t get away, that can’t afford the trip,” she said. “You’re hurting people who are already down.”

About 85% of women seen at Texas clinics before the law passed would no longer qualify because they’re past the six-week limit, clinic staffers said.

Whole Woman’s Health, which has four clinics in Texas, has provided about half as many abortions each week since the law took effect: 91 a week compared with 195 a week before the law, a spokeswoman said.

More than half a dozen states have tried to ban abortion during the coronavirus outbreak as an elective procedure.

So far, no lawsuits have been filed under the law, said John Seago, legislative director for Texas Right to Life, who helped craft it.

But Seago said the group, which set up a website for those seeking to enforce the law, has been “monitoring closely all of the public statements from the abortion providers as well as their status as a clinic.”

Seago said the law applies only in Texas, that it’s not illegal for Texas women to travel out of state to get abortions or for people to help them. But he said some women are not making it that far.

“A lot of those patients who are getting turned away are ending up at pregnancy resource centers usually across the street or nearby,” Seago said — facilities run by antiabortion groups, including Choices Medical Clinic next door to Trust Women in Wichita.

Outside the Wichita clinic, antiabortion protesters praised the Texas law and said they had been gearing up to intercept the influx of patients.

“They told us to get ready because people are going to come from south and all over to get here,” said Joseph Elmore, 73, who was protesting outside the clinic during his day off in front of a Kansas Coalition for Life truck that said, “Every abortion is an act of violence!”

Elmore, a substitute teacher, called the Texas law “encouraging.”

“Finally people are going, ‘We’re up to our necks in blood, it’s got to stop,’” said protester Laura Goetz, 57, calling the Texas law “a start.”

Inside the clinic, the director — who has a clothes hanger tattooed behind her ear — said the law had been demoralizing.

“This is as close as we’ve come to Roe falling. It’s going to get bad. It’s already very bad,” Brink said as she sat in her office next to a sign that said, “Keep Abortion Safe.”

In California, Planned Parenthood clinics have already started seeing two to three added patients a day from Texas since the law took effect, spokesman Brandon Richards said, and they expect the influx to increase, “especially if other hostile states adopt a similar law.”

Planned Parenthood of the Rocky Mountains saw the number of Texas patients at its clinics in Colorado and New Mexico increase from eight to about three dozen after the law took effect, a spokeswoman said.

“What we’re seeing more are people who don’t have the resources to stay in Kansas, Oklahoma, these states that have arbitrary two-, three-day waiting periods. The people we’re seeing, they can’t take that much time off, they don’t have the supports,” said Joan Lamunyon Sanford, executive director of New Mexico Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, which offers logistical support to those seeking abortions in Albuquerque.

They are fielding double the number of calls, raised about $20,000, attracted nearly three dozen volunteers and are adding trainings, she said.

Emily Wales, chief executive of Planned Parenthood Great Plains, said the organization started to see an increase in Texas patients even before the law passed at its clinics in Arkansas, Kansas and Oklahoma, where it sued to block the proposed “heartbeat law.”

“Folks are begging friends to help them get to care. Many of them are very, very concerned about the cost, their family obligations,” she said.

The Texas law increased regional abortion costs, which were already higher than in California because clinics such as Trust Women have to fly doctors in from other states — including California — and only certain local businesses will work with them, Brink said.

Texas women are more likely to be uninsured and pay more for abortions because the state has both the highest rate and number of uninsured people in the country.

The average out-of-pocket cost of abortion varies nationwide depending on insurance coverage, from $300 to $1,500 for medication abortion, and $295 to $1,600 for surgical abortion, according to a California legislative analysis this year.

Trust Women charges $650 for medication and surgical abortion; after the first trimester, women pay more than $750. Anesthesia costs $150 more, plus women must arrange for someone to drive them home or find a place to stay overnight.

Texas has almost 7 million women of reproductive age, about 1 in 10 in the country, according to the Guttmacher Institute. Last year, Texas doctors performed about 55,000 abortions, while doctors in states such as Kansas did far fewer — about 7,500. The closest clinics can’t absorb all of the Texas patients, who are already going farther afield, displacing patients in surrounding states.

Last week, two women separately drove about a day from Texas’ Rio Grande Valley on the Mexico border to out-of-state clinics: one to New Mexico, the other to Shreveport, La., clinic staff members said. Both had to show they were in the country legally to clear Texas Border Patrol checkpoints.

It’s not clear what migrant women living in Texas illegally will do, said Zaena Zamora, the Rio Grande Valley-based executive director of the nonprofit Frontera Fund that helps local women seeking abortions.

“We’re leaving out a population who’s vulnerable who are at the mercy of this law,” she said.

A handful of abortion funds have set up websites to help women find clinics and pay for abortions. But fewer women have been seeking assistance, said Davé, the Lilith Fund acting director. She said they receive as few as 10 calls a day, a third to a fifth of what they received before the law.

“People are scared that abortion is illegal and that they will be penalized for seeking care,” Davé said. “We need this law to be struck down. We are already nearly living in a post-Roe Texas. The vast majority of women who need to access abortion care can’t.”

The same day the Justice Department sued to block the Texas law last week, Vice President Kamala Harris met with abortion providers from Texas and surrounding states at the White House, including Dr. Bhavik Kumar, staff physician at Houston’s Planned Parenthood Center for Choice. Kumar said the meeting and lawsuit left him “reassured that the administration was doing everything they could to help us maintain access.”

Kumar said he’s had patients arrive for appointments who qualified for abortions under the new law only to return after the state’s mandatory 24-hour waiting period and no longer qualify because fetal cardiac activity was detected. He said he was concerned about patients with medical complications having to travel for abortions, or being unable to travel, forced to carry hazardous pregnancies to term.

“We’re going to see effects on maternal morbidity and mortality,” Kumar predicted, which were already high in Texas, “comparable to developing countries.”

In Wichita on Thursday, Meagan took her abortion medication and prepared to return to Texas.

“I’m glad I was able to get the help I needed,” she said.

But with the Justice Department lawsuit pending, she said she felt fellow Texans seeking abortions were still at risk, “until the law’s settled.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.