‘Was it worth it?’ A fallen Marine’s family and a war’s crushing end

SPRINGVILLE, Tenn. — She was folding a red sweater when she heard a car door slam, went to the window and realized that a moment she always imagined would kill her was about to be made real: three Marines and a Navy chaplain were walking toward her door, and that could mean only one thing.

She put her hand on the blue stars she’d stuck next to the front door, a symbol meant to protect her son, Marine Lance Cpl. Alec Catherwood, who had left three weeks before for the battlefields of Afghanistan.

And then, as she recalls it, she lost her mind. She ran wildly through the house. She opened the door and told the men they couldn’t come inside. She picked up a flower basket and hurled it at them. She screamed so loud and for so long the next day she could not speak.

“I just wanted them not to say anything,” said Gretchen Catherwood, “because if they said it, it would be true. And, of course, it was.”

Her 19-year-old son was dead, killed fighting the Taliban on Oct. 14, 2010.

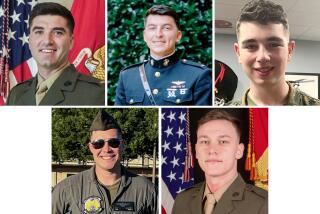

As she watched the news over the last two weeks, it felt like that day happened 10 minutes ago. The American military pulled out of Afghanistan, and all they had fought so hard to build seemed to collapse in an instant. The Afghan military put down its weapons, the country’s president fled and the Taliban took over. Then suicide bombers killed several U.S. military members, including at least 11 Marines, in attacks Thursday at the Kabul airport, where thousands have been trying desperately to escape.

Gretchen Catherwood felt as if she could feel in her hands the red sweater she’d been folding the moment she learned her son was dead.

Her phone buzzed with messages from the family she’s assembled since that horrible day: the officer who’d dodged the flowerpot; the parents of others killed in battle or by suicide since; her son’s fellow fighters in the storied 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, nicknamed the Darkhorse Battalion, that endured the highest rate of causalities in Afghanistan. Many of them call her “Ma.”

Outside of this circle, she’d seen someone declare “what a waste of life and potential” on Facebook. Friends told her how horrible they’d felt that her son had died in vain. As she exchanged messages with the others who’d paid the price of war, she worried its end was forcing them to question whether all they had seen and all they had suffered had mattered at all.

“There are three things I need you to know,” she said to some. “You did not fight for nothing. Alec did not lose his life for nothing. I will be here for you no matter what, until the day I die. Those are the things I need you to remember.”

In the woods behind her house, the Darkhorse Lodge is under construction. She and her husband are building a retreat for combat veterans, a place where they can gather and grapple together with the horrors of war. There are 25 rooms, each named after one of the men killed from her son’s battalion. The ones who made it home have become surrogate sons, she said. And she knows of more than a half a dozen who have died from suicide.

“I am fearful of what this might do to them psychologically. They’re so strong and so brave and so courageous. But they also have really, really big hearts. And I feel that they might internalize a lot and blame themselves,” she said. “And, oh, God, I hope they don’t blame themselves.”

Into a Taliban stronghold

The 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment deployed in the fall of 2010 from Camp Pendleton in California, sending 1,000 U.S. Marines on what would become one of the bloodiest tours for American service members in Afghanistan.

The Darkhorse Battalion spent six months battling Taliban fighters in the Sangin district of Helmand province. An area of green fields and mud compounds, Sangin remained almost entirely in the Taliban’s control nearly a decade into the U.S.-led war. Fields of lush poppies used in narcotics gave the militants valued income they were determined to hold.

When the Marines arrived, white Taliban flags flew from most buildings. Loudspeakers installed to broadcast prayers were used to taunt U.S. forces. Schools had closed.

The Marines came under fire as soon as a helicopter dropped them outside their patrol base.

“When the bird landed, we were already getting shot at,” recalled former Sgt. George Barba of Menifee, Calif. “We run, we get inside and I remember our gunnery sergeant telling us: `Welcome to Sangin. You just got your combat action ribbon.’”

Snipers lurked in the trees. Fighters armed with rifles hid behind mud walls. Homemade bombs turned roads and canals into deathtraps.

Sangin was Alec Catherwood’s first combat deployment. He had enlisted in the Marines while still in high school, went to boot camp shortly after graduation, then was assigned to a 13-man squad led by former Sgt. Sean Johnson.

Johnson was impressed by Catherwood’s professionalism — physically fit, mentally tough and always on time.

“He was only 19, so that was extra special,” Johnson said. “Some are still just trying to figure out how to tie their boots and not get yelled at.”

Catherwood also made them laugh. He carried around a small, stuffed animal he used as a prop for jokes.

Barba recalled Catherwood’s first helicopter ride during training and how he was “smiling ear-to-ear and he’s swinging his feet like he’s a little kid on a highchair.”

Former Cpl. William Sutton of Yorkville, Ill., swore Catherwood would crack jokes even during a firefight.

“Alec, he was a shining light in that darkness,” said Sutton, who was shot multiple times fighting in Afghanistan. “And then they took it from us.”

On Oct. 14, 2010, after a late night standing watch outside their patrol base, Catherwood’s squad headed out to assist Marines under attack who were running low on ammunition.

They crossed open fields, using irrigation canals for cover. After sending half his squad safely ahead, Johnson tapped Catherwood on the helmet and said: “Let’s go.”

After running just three steps, he said, gunfire from ambushing Taliban fighters sounded behind them. Johnson looked down and saw a bullet hole in his pants where he had been shot in the leg. Then came a deafening explosion — one of the Marines had stepped on a hidden bomb. Johnson blacked out momentarily, waking up in the water.

Another explosion followed. Looking to his left, Johnson saw Catherwood floating facedown. It was obvious, he said, that the young Marine was dead.

Explosions during the ambush killed another Marine, Lance Cpl. Joseph Lopez of Rosamond, Calif., and badly wounded another.

Back in the United States, Staff Sgt. Steve Bancroft began an excruciating two-hour drive toward Catherwood’s parents’ house in northern Illinois. He’d served seven months in Iraq before he became a casualty assistance officer, tasked with notifying families of a death on the battlefield.

“I’d never wish that on anybody, I can’t express that enough: I do not wish looking a mom and dad in the face and telling them their only son is gone,” said Bancroft, who is now retired.

He was stoic as he escorted families to Dover, Del., to watch coffins be rolled out of a plane. But when he was alone, he cried. And he still weeps when he thinks about the moment he arrived at the home of Gretchen and Kirk Catherwood.

They laugh now about the hurled flowerpot. He still regularly talks to them and other sets of parents he notified. Though he never met Alec, he feels he knows him.

“Their son was such a hero, it’s hard to explain, but he sacrificed more than 99% of the people in this world would ever think of doing,” he said.

“Was it worth it? We lost so many people. It’s hard to think about how many we’ve lost.” he said.

Making it home, yet not

Gretchen Catherwood keeps the cross her son was wearing on a chain around her bedpost with his dog tags.

Alongside it hangs a glass bead, blown with the ashes of another young Marine: Cpl. Paul Wedgewood, who made it home.

The Darkhorse Battalion returned to California in April 2011. After months of intense fighting, it had largely seized Sangin from the Taliban’s grip. Leaders of the provincial government could move about safely. Children, including girls, returned to school.

It came at a heavy price. In addition to the 25 who perished, more than 200 returned home wounded, many with lost limbs, others with scars harder to see.

Wedgewood had trouble sleeping when he finished his four-year enlistment and left the Marine Corps in 2013. As he slept less, drank more.

A tattoo on his upper arm showed a sheet of scroll paper bearing the names of four Marines who died in Sangin. Wedgewood considered reenlisting but told his mother: “If I stay, I think it’ll kill me.”

Instead, Wedgewood enrolled in college back home in Colorado but soon lost interest. A welding program at a community college proved a better fit.

Wedgewood had been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. He was taking medication, participating in therapy.

“He was very engaged in working on his mental health,” said the Marine’s mother, Helen Wedgewood. “He was not a neglected veteran.”

Still, he struggled. On the Fourth of July, Wedgewood would take his dog camping in the woods to avoid fireworks. He quit a job he liked after a backfiring machine caused him to dive to the floor.

Five years after Sangin, things appeared to be looking up. Wedgewood was preparing for a new job that would take him back to Afghanistan as a private security contractor. He seemed to be in a good place.

After a night of drinking with his roommates, Wedgewood didn’t show up for work on Aug. 23, 2016. A roommate later found him dead in his bedroom. He had shot himself. He was 25 years old.

He left a short note.

“He basically said that he loved us, but he was tired,” Helen Wedgewood said.

She considers her son and others who took their own lives to be casualties of war every bit as much as those killed in action.

When the Taliban swept back into control of Afghanistan just before the fifth anniversary of her son’s death, she felt relief that a war that left more than 2,400 Americans dead and more than 20,700 wounded had finally come to an end. But there was also sadness that gains made by the Afghan people — especially women and children — may be temporary.

“As a mom, this kind of stabs you, because would he still be around, would any of these young men still be around if this whole war hadn’t happened?” she said. “But I try to gently correct people when they say this was a waste or this was all for nothing. Because that’s not true. We don’t know what impacts it’s had on the safety of our country, on the safety of the Afghan people.”

What did it all mean?

Some who served with the Darkhorse Battalion are having a hard time seeing it any way other than that their efforts, their blood and the lives of their fallen friends were all for nothing.

“I’m starting to feel like how the Vietnam vets felt. There was no purpose to it whatsoever,” said Sutton, 32, who now works in the veterans services office of a county outside Chicago, helping military vets get care.

“We were able to hold our head up high and say we went to the last Taliban stronghold and we gave them hell,” Sutton said, “only for it all to be taken away. In the blink of an eye.”

Barba, 34, works as a private security guard near Los Angeles. He and his wife are expecting their first child. He said he’s had trouble sorting his feelings about the bleak news from Afghanistan. His wife recently woke to Barba screaming in his sleep. “I think your nightmares are back,” she told him.

“It really is weird,” Barba said. “I’ve seen my guys get mad. I’ve seen my guys get frustrated. But not like this. This is like somebody spit in their face.”

Johnson, 34, works as a commercial diver in Florida. He said the U.S. should have acknowledged years ago that the Afghan security forces Americans trained and equipped would never be able to defend the country on their own.

“My personal opinion, yeah, we probably should have pulled out years and years ago,” Johnson said. “If you’re not going to win the damn thing, what are you doing there?”

‘Like they’re together’

A few months ago, Gretchen Catherwood was painting the cabins that will become the Darkhorse Lodge. It was dark, still without electricity and no cell service, so it was quiet. She felt suddenly like she could feel her son and his 24 fallen comrades. She could almost see their faces.

“It’s a place where I can feel like they’re together,” she said, “and that they are still caring for their brothers.”

The Catherwoods moved out of their home in Illinois. Every time she walked to the front door, Gretchen remembered those four men arriving with the news. She couldn’t bear it anymore.

The gold star pins she wore everyday on her chest kept breaking. She’d always disliked tattoos and hassled her son when he got one as a Marine. But then she found herself at a tattoo parlor. She had his name inked on her arm, and the shape of a gold star pin put permanently on her chest, just above her heart, so she’d never take it off again.

She could no longer care for her son, she said, but she could for those who made it home. She and her husband moved to the woods in Tennessee and got to work on the Darkhorse Lodge.

They fashioned their logo after the battalion’s mascot, a fierce-looking horse, facing left, its mane sharp like a serrated knife and its eyes squinted for battle. The artist who drew theirs softened its edges and turned it to the right, facing toward a future after war.

They raised $! million dollars, mostly in small donations. One woman sends a check for $2 every month. Bancroft, the officer who notified her of her son’s death, donates every year. The obituary for one soldier who died by suicide asked for donations to the Darkhorse Lodge in his memory, and checks flooded the Catherwoods’ mailbox.

They hope to open next summer and offer free stays for any combat veteran from any war or branch of the military who might benefit from time in the woods, where the only conflict is among the dozens of hummingbirds fighting over the feeders on her front porch.

She is hopeful that the American withdrawal from Afghanistan means no one else will die on a battlefield there. But she also worries that it might rattle the vets who made it home and who might already be struggling to make sense of what happened there and why.

“That’s a constant fear; it’s been my fear since they got back, but now it’s even worse,” she said. “They experienced things that 99% of the country never will. I’ve never watched a friend die. I’ve never fought to the death. We are losing these people at a frightening, frightening rate to suicides, and we can’t afford to lose one more.”

She and her husband don’t believe that the chaotic end honors their son’s service and are particularly troubled that some of the Afghan interpreters and others who helped the military for years might not make it out alive. But they also can’t imagine how it might have ended any other way, had the United States stayed in Afghanistan another year or five or 20.

Part of Alec Catherwood remains there, and for a while that bothered his mother.

When he was alive, she loved to touch his face. He had baby soft skin and when she put her hands on his cheeks, this big tough Marine felt like her little boy. The military did an honorable job making him look whole, she said. But when she touched his cheek as he laid in the casket, she touched a part that had been reconstructed — it wasn’t really him.

“That used to be much harder than it is now,” she said. “Now, it’s like, damn straight, he’s still there. He’s always going to have a presence there, flipping off the Taliban.”

Good things will grow where he is, she likes to think.

“He’s part of their dirt, their soil, he’s part of the Earth there, he is forever there.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.